As the underground filmmaker passes away, we revisit a 2014 interview with him about his lifelong obsession with the occult

“I was raised a Presbyterian, but rejected Christianity at the age of eight, when my parents tried to make me go to Sunday school. It was not an ideological position; I just wanted to read the Sunday funny papers. It wasn’t until I was a teenager that I became interested in the occult, after reading Sir James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough, a comparative study of mythology and religion. Soon after that, I was introduced to the works of Aleister Crowley by Marjorie Cameron, a very good friend who was also, without any doubt, a genuine witch, in a good sense. She had what you’d call ‘powers’. She was married to Jack Parsons, a pioneer in developing the rocket fuel that would later take man to the Moon.

“After his death in 1952, Marjorie and I lived together and studied the Crowleyian teachings. Crowley, one of the most extraordinary Englishmen of the Edwardian – or indeed any other – era, was a poet, mountaineer, ritual magician and libertine who created his own religion and philosophy, Thelema. The word, in classical Greek, signifies the appetitive will; desire, sometimes even sexual. Unsurprisingly, the British yellow press deemed him ‘the wickedest man in the world’. That was part of his aura, his halo. His attitude toward sex being sacred and having mystic qualities, it’s not surprising he should have been controversial. He was really like a diabolical little boy.

“I like to express my beliefs through cinema. After all, movies can be the equivalent of mantras” – Kenneth Anger

“I guess you could say I am a Pagan. But Paganism, after all, is nothing but appreciation of nature. It has nothing to do with so-called ‘black magic’. I am also a member of the Ordo Templi Orientis (the Order of the Temple of the East), a secret society founded in the early 20th century. I don’t like to talk about my own rituals and practices (contrary to popular belief I’m not doing magic circles all the time, although I have done them on occasion), but they have obviously influenced my work.

“Lucifer Rising was a celebration of the beginning of the Pagan age and the end of Christianity, where Lucifer was elevated from his place in Christian belief as a fallen angel to his pantheistic role as bringer of light … I like to express my beliefs through cinema. After all, movies can be the equivalent of mantras. They cause you to lose track of time and to become disoriented because magical things can happen. Movies can also be evil – although, of course, my definition of evil is not everybody else’s. Evil is being involved in the glamour and charm of material existence, glamour in its old Gaelic sense meaning enchantment with the look of things, rather than the soul of things.”

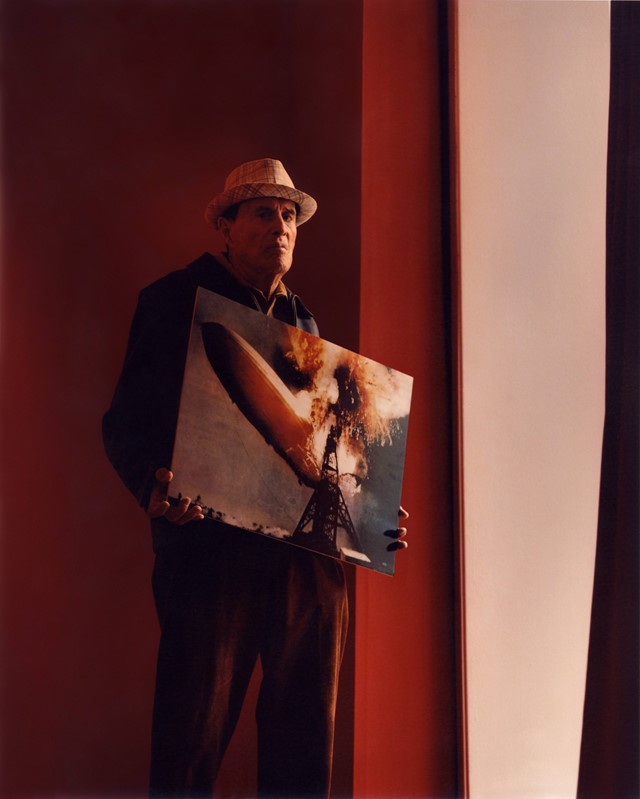

Born in Santa Monica in 1927, Kenneth Anger is the US’s most celebrated underground filmmaker, named as a major influence by directors as disparate as Martin Scorsese, David Lynch and John Waters. An avid cinephile with a taste for camp (he is the author of Hollywood Babylon, a book detailing the sordid scandals of early movie stars and responsible for several urban legends), he produced a substantial body of work between the forties and the seventies: films about beauty, sex and magic that have the feverish, hallucinatory quality of dreams or acid trips.

His first distributed work, titled Fireworks and made in 1947, was a homoerotic, masochistic fantasy in which a young man (Anger himself) was brutally beaten by a group of sailors. His 1963 film Scorpio Rising (another non-narrative sadomasochistic masterful montage of leather and chrome fetishism, six-packs, scorpions and swastikas) has possibly the best pop soundtrack in movie history: The Angels’ My Boyfriend’s Back, Ricky Nelson’s Fools Rush In and The Shangri-Las’ The Leader of the Pack would later encourage Scorsese and Lynch to use pop songs to help tell a story.

His magnum opus, Lucifer Rising (1972) was ten years in the making. It was set to star Mick Jagger as Lucifer, but while the singer eventually backed out, his then-girlfriend Marianne Faithfull did appear in the film as the demon Lilith rising from the sarcophagus. The soundtrack was created by Bobby Beausoleil, a follower of Charles Manson who was convicted for murder in 1970, and who wrote most of the score in prison. Anger seems to have an uncanny ability to gravitate towards some of the most intriguing figures of the 20th century: as a boy he danced on stage with Shirley Temple and later became close friends with the sexologist Alfred Kinsey (who bought a copy of Fireworks in 1947 for his archives), Anaïs Nin (who once described Anger as “living entirely in a world of his own”) and Jean Cocteau, one of his biggest fans.