The true crime industry is a relatively new phenomenon, and it’s yet to iron out a number of chilling contradictions. Netflix heartthrobs cast in the role of necrophiliac murderers and sex offenders; grisly tales about the darkness of the human soul interrupted for a peppy toothbrush ad read (that’s what keeps this podcast free, folks!); stories told about society’s most vulnerable, to line the pockets of society’s most secure. Eliza Clark’s second novel, Penance, takes us deep inside this absurd world, exposing how a real, horrific crime against a teenage girl attains cult status, filters through podcasts and Reddit threads, and ends up here, as the book you hold in your hands.

Eliza Clark isn’t actually narrating a true crime, of course. The metafictional story is told from the perspective of an upper-middle-class man, Alex Carelli, whose efforts to construct a compelling narrative out of the murder of a teenage girl – by a group of other teenage girls, on the eve of the Brexit vote – takes him to their Leave-voting seaside town of Crow-on-Sea, where he picks at the scabs of their parents, siblings, teachers, and former friends.

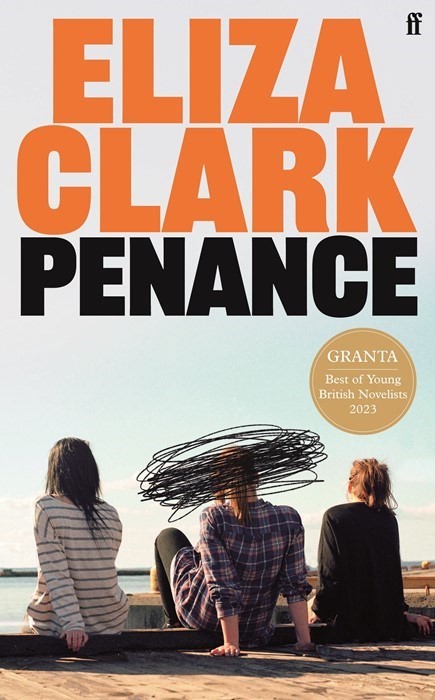

In this sense, the book is a radical departure from Clark’s 2020 debut, Boy Parts, a hallucinatory story told from the perspective of a young photographer, Irina, whose sense of her own invisibility escalates toward violence. (In 2023, Boy Parts helped land Clark on Granta’s once-a-decade list of the best young British novelists.) Penance’s dark humour occupies a similar space, however, as do its keen observations on the edgier niches of internet culture in the mid-2010s, explored in passages that ricochet between the crime itself, the witch-hunting history of Crow, and the precarious landscapes of pre-censorship Tumblr and true crime message boards.

Below, we speak to Eliza Clark about the radicalising force of online communities, the twisted politics of true crime, and how post-Brexit Britain turned into its own pocket hell.

Thom Waite: What initially drew you to the subject of true crime?

Eliza Clark: In terms of it being a departure from Boy Parts, that was in a lot of ways quite intentional. I wanted to do something that was more ambitious, to prove that I could do something different and to avoid being pigeonholed. But I think that the true crime stuff is just out of personal interest. It’s always been something that I’ve been interested in, but it was something that I was getting increasingly critical of, and my relationship with [it] changed quite a lot while I was writing Penance as well. I’d always thought of myself as rubbernecking true crime.

TW: What was the research process like for Penance?

EC: A lot of it was just osmosis. Penance is actually based on a couple of cases. The case that it’s most similar to is the Shanda Sharer murder, which happened in the mid-1990s in the states. It also draws some points of similarity from the Suzanne Capper murder, which was also a mid-90s thing in the UK. But once I realised I was going to be drawing from those cases, I decided not to do any additional research. I was just using the rough bullet points that I remembered, rather than doing a direct fictionalisation. I don’t know if I would have felt particularly comfortable with that. Sometimes I don’t really feel particularly comfortable with the fact that I’ve used real cases at all.

“Unfortunately, I had no need to trawl Tumblr, because it was all seared into my brain in a way that, tragically, required absolutely no research” – Eliza Clark

TW: And how did you land on the male, upper-middle-class narrator?

EC: I knew that I definitely wanted to have a journalist, and there was a more interesting power differential there with a male journalist. And I knew I wanted him to be a member of Britain’s media class. I hadn’t really decided on his background initially ... but I found that when I was trying to ape the true crime, nonfiction voice, it just sounded so pompous and self-important. Then, I read In Cold Blood while I was writing Penance, and I was really interested in reading afterwards that Capote had actually fabricated a lot of the material. I was really interested in the weirdness but also the arrogance of that, and the psychology of the kind of person who decides that they are the arbiter of the narrative.

TW: Do you think true crime is, to some extent, more palatable when establishment media reports on it, rather than Netflix or podcasters?

EC: For me, the most considered and interesting sort of true crime reporting has been in longform books that spend a lot of time with the victim and the broader sociopolitical context of the murder, which is something that a book gives you space to do, rather than just an hour of documentary, where you’ve got to get people to go on to the next episode, or an hour-long podcast where you really need to get your mattress advert in.

Unfortunately, some good true crime podcasts I’ve listened to [are] so undermined by the presence of aggressive advertising. [A podcast] that had quite a big impact on me is called Broken Harts, about this absolutely appalling abuse case of five Black children who were adopted by a white couple, who used the kids really aggressively on social media, essentially building lefty kudos. Then, when they were in the process of being caught for abuse and neglect, they drove all of the children off a cliff, including themselves. It’s just an absolutely awful, awful, awful case. But the podcast was pausing every 15 minutes to advertise toothbrushes.

“Seaside towns feel like a place that is universal in the British psyche, and the way those spaces shifted in the last half a century felt like very fertile ground” – Eliza Clark

TW: Could you tell us a bit about constructing this fictional seaside town in decline, set between real locations on the east coast?

EC: My partner spent his teenage years in Scarborough, his parents still live there, and we’ve got a lot of friends from there, so I was pulling on weird little anecdotes that I’ve heard. Seaside towns are just very interesting and universal places. Everybody has been to one; if they haven’t personally lived in one, they might have had one that they visited when they were a kid. It feels like a place that is universal in the British psyche, and the way those spaces shifted in the last half a century felt like very fertile ground to pick apart and embellish. It did take years to work out properly. It felt like world building, almost a speculative fiction kind of exercise. League of Gentlemen ended up being quite a big influence.

TW: The seaside town also allows you to draw out these polarised class dynamics, especially in the lead-up to the Brexit vote. Why did you choose that period for the murder to take place?

EC: That was actually something that I kind of pinched from the Suzanne Capper case, which basically got completely buried. Nobody has heard of the case, even though it’s this very extreme, shocking incident that happened. I was interested in the idea of a crime that is completely buried in the news cycle, and I needed something big that was going to dominate the news cycle, to give the crime this kind of undiscovered status.

It’s funny, because Penance ended up having this extra, ‘state of the nation’ layer to it, which I was really conscious of when I was writing it. I didn’t want people to think that I’ve deliberately set out to write a Brexit novel. But I don’t know, maybe I have ended up making a political point.

“Britain is a pocket hell of its own design, especially right now” – Eliza Clark

TW: One of the girls in Penance is obsessed with creating ‘pockets of hell’ – places to manifest and spread evil energy – which feels like a darkly comic parallel to post-Brexit Britain.

EC: I think in many ways, Britain is a pocket hell of its own design, especially right now. Things weren’t quite as bad while I was writing Penance. I know things have been gradually taking a dive, but I suppose that’s just the experience of Britain for the last ten years, just saying ‘God, things have really taken a dive’ once every six months.

TW: Do you think a social media platform like Tumblr actually helps radicalise young people, and drive them to commit real acts of violence, as it does in Penance?

EC: Completely, it does. We only need to look at the political dissent of a lot of terminally online young men in the last ten years, in terms of the fascist resurgence: a lot of people descending from being irony-poisoned to just being out-and-out racist. It’s not so much that social media specifically is bad, [but] I do think there’s a lot of stuff about the internet that people don’t understand and can’t handle to a degree. I just don’t think the human brain is designed to come into contact with this many people and this much information, and I think that’s going to be a multi-generational adjustment, to the existence of the internet.

It’s really weird and dangerous that a lot of kids have access to adults who are complete strangers. A lot of that has come out in the increase of online radicalisation. I’m friends with a few secondary school teachers, and the amount of damage that young boys having access to Andrew Tate’s rhetoric has done has been really major in the last couple of years. Particularly when teenagers are so impressionable, and malleable, to be given access to a lot of weird adults with strange opinions is maybe not the best thing in the world. I don’t want to do a pearl-clutching, ‘Won’t somebody please think of the children’ kind of thing, but I do think we’ve got this incredibly powerful, society-up-ending tool that we don’t properly know how to use.

Penance by Eliza Clark is published by Faber and is out now.