You never forget your first love. Awkward newly-out Tom, uncomfortably shuffling around a student drag party in a leopard-print dress, meets playwright Ming, whose charm, wit and laconic comfort in his own queerness quickly put Tom at ease. They fall for each other fast and hard, but Ming’s confidence belies deep-seated troubles with OCD, grief and more inchoate feelings of distress, which threaten to engulf him entirely after graduation. One day, Ming tells Tom that he doesn’t want to be a man anymore. Her decision to transition forms a turning point in their relationship, but it is one of various decisions they both make – separately and together – that change their lives completely. How do you figure out how to do what is right? And how do you manage the unexpected effects of your choices?

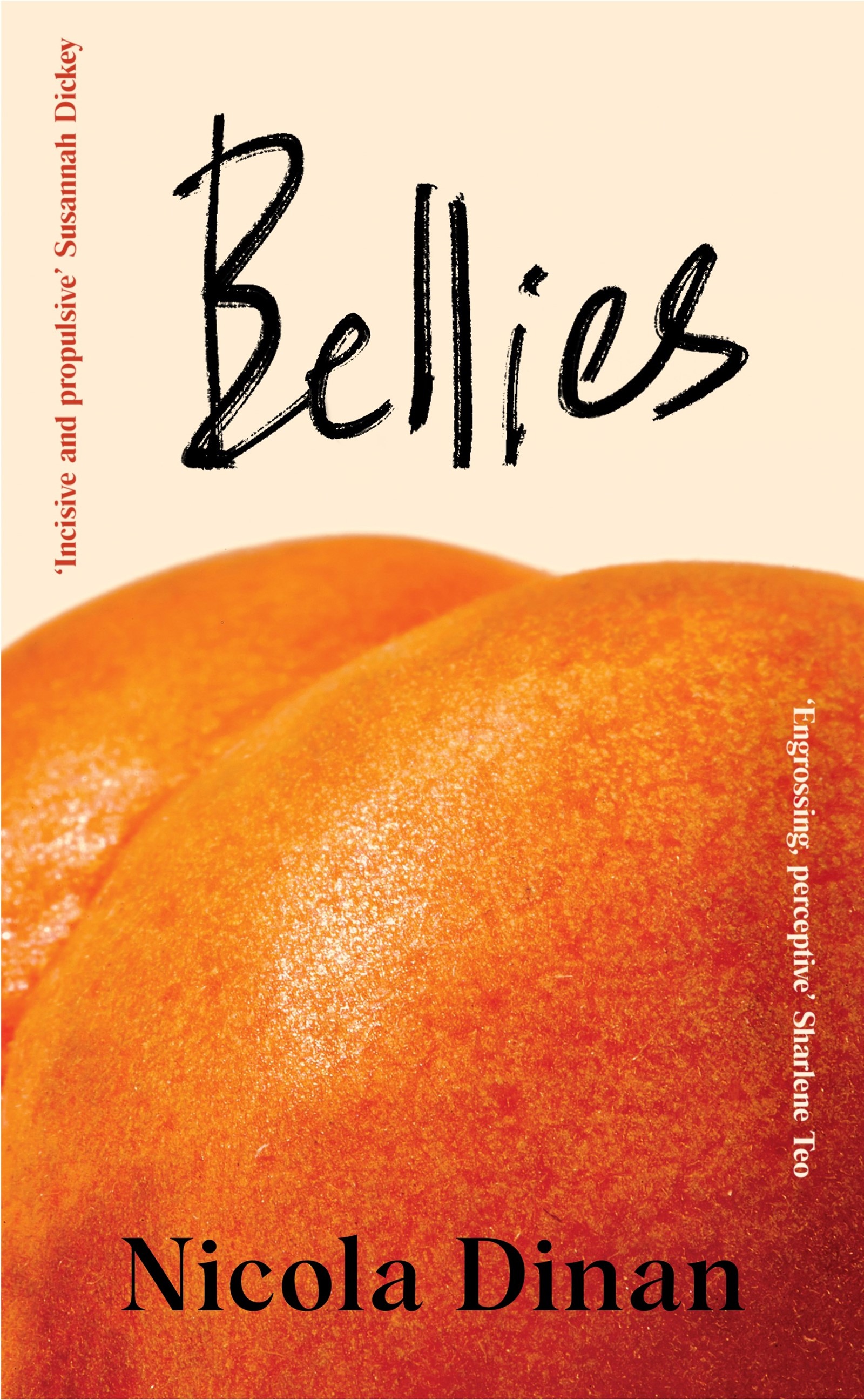

Written by Nicola Dinan, who grew up in Hong Kong and Kuala Lumpur and studied Natural Sciences at Cambridge University before training as a lawyer, Bellies is a captivating read, heady with the whirlwind feelings of early-twenties post-university life: it’s sensual, witty, nostalgic and captures the dizzying feeling that the world has both massively expanded and become scarier, less warm. But the novel is underpinned by both a sharp, piercing intelligence and a boundless sense of compassion. Everyone hurts other people, particularly when they are young and selfish and scared, and yet most people are trying their best; they can grow, repair, do better. Beyond just being a love story, Bellies is a relationships story, unsparing yet optimistic about our abilities to understand each other, connect to each other and heal.

Over Zoom, AnOther spoke to Dinan about transition stories, writing Malaysian food, and what’s in her Bellies playlist.

Eli Cugini: So, you’re a debut author in your late twenties, writing about university and post-university students in their early twenties, and their attendant heartbreaks, griefs, interpersonal affections, cruelties. Bellies is already drawing the expected comparisons to the work of Sally Rooney, Brandon Taylor, and others. Who are your main influences?

Nicola Dinan: There’s something strange about how, when you’re publishing a book, you have to actively position yourself in relation to other authors – ‘for fans of … ’ – when I think the ways we’re influenced by other writers, and in conversation with other writers, are often so much more subtle and indirect. Some of the biggest influences on my writing have been writers like Rachel Cusk or James Baldwin, and I’m not sure you would even see that in the way that I write. My prose style is so different to Rachel Cusk’s, but you can feel that influence in the way that dialogue is approached, for instance.

Who I’m influenced by and who I’d be put next to are quite different sets, I think, but I’m so grateful to writers like Bryan Washington, Brandon Taylor, Torrey Peters as well. I think it’s interesting that we might have very different influences, and yet our works can end up having this affinity with each other.

EC: The book has two POV characters; it’s quite rare that a book’s empathy and focus is so evenly shared between two characters even though they’re so different. It would have been very easy for the book to devote more empathic resources to one character than the other, but it stays very balanced.

ND: It would have been easier to devote those resources to Ming, for sure. What’s interesting is that I think some would expect a book which has transitioning at its centre to entirely focus on the trans character, but while transitioning is an essential plotline of the novel, more than anything it’s a novel about relationships, love, how love transforms from one thing to another. Part of why I wanted to include Tom’s voice as well is to centre the relational aspect of the change that’s going on in Ming’s life; suddenly something that feels so obscure and specific to so many people, transitioning, becomes a little more universal. It becomes this thing that could be akin to a geographical move, or a bereavement, all these things that happen in our relationships that change how we relate to one another, and can, potentially, pull us apart.

EC: We see Tom and Ming at their best and their worst, and at times I found it genuinely challenging to keep seeing the world through their eyes. What’s your view on the benefits of keeping narrative focus and empathy on characters who are being unlikeable, foolish, or cruel?

ND: Sometimes, to truly empathise with characters, they need to be a bit cruel. They need, at times, to be unfair and unreasonable, because people are unfair and unreasonable. I don’t want people to read Bellies and empathise with Bellies because they think they’re seeing their best selves in the novel. It’s far more interesting to reflect people as they are. I don’t think we learn from characters that are overly virtuous, particularly if they’re minorities like Ming – it just reaffirms the fear that we are not entitled to the same flaws and spectrum of emotions as everyone else, and that is damaging. Everyone in the book is flawed. You have Tom’s best friend Rob, who is a bit of a shit to girls, but at the same time is a really lovely supportive loyal friend. You have Ming’s dad, who genuinely wants what’s best for Ming, but it’s his own vision of what’s best for Ming, not necessarily hers.

EC: One thing that really struck me in Bellies was the descriptions of food – there’s a lushness to them, and they’re used to convey a sense of place and also orient the characters in relation to each other. What made you return to food so often in the novel?

ND: The most vivid descriptions of food come early on in the book when Tom and Ming go to Kuala Lumpur, which is where I grew up. If you grow up somewhere like Malaysia, food is such an integral part of your life, especially in a culture where saying “I love you” is less common, where communicating love via words isn’t something done as often as it is elsewhere. Food is such a clear medium to convey affection, it’s very sensual, it connects you to forms of sensory memory, and it’s something Ming reaches for when she’s out of Malaysia and feeling that sense of loss. It’s a way to situate herself back in a place she’s been displaced from. I couldn’t have written Malaysia without food.

“Some would expect a book which has transitioning at its centre to entirely focus on the trans character, but while transitioning is an essential plotline of the novel, more than anything it’s a novel about relationships, love, how love transforms from one thing to another” – Nicola Dinan

EC: You’re currently adapting Bellies for the screen; the atmosphere of the book feels so distinct that I found myself wondering, was there any music you’d want to use in a TV adaptation, or that you think would be good to listen to while reading it?

ND: I have a Bellies playlist! It was fun to think about what music goes with each chapter – the novel has a very nostalgic feel to it, because it draws on this nostalgic time, being in your early twenties at university and finishing university. It’s also situated in the late 2010s and early 2020, so there’s a specific period it’s drawing on. You’ve got some Shygirl in there, some Hot Chip, a good chunk of Azealia Banks, and there are songs that are specifically referenced in the book like Aphex Twin and Don’t Stop Now by Dua Lipa. And it ends on Ribs by Lorde, of course.

EC: It felt very specifically late 2010s – I started transitioning a little while after Ming does in the novel, and it feels like if she’d started three years earlier or three years later, her experience would have been very different.

ND: There are so many ways in which life has changed, for better or worse, for trans people, and particularly looking at the legislative landscape now, I want the book to be situated in the time that it’s in so that it feels true to that time period and people read it in the right context so as not to misrepresent the experiences of a character like Ming. I don’t have any shame about the book having a temporal link. I want it to age. I had a conversation with my editors about whether the age of cultural references in the novel will mean that it ages – will it be jarring when someone picks it up in five or ten years? I do try to maintain a sense of timelessness. I do find it jarring when I read a book written in 2017 and there’s a reference to Facebook, but I also really enjoy the idea of people picking the book up in ten years and knowing it relates to that time period and feeling connected to people who are a bit older than them.

EC: Given that focus on potential legacy, what would you most like readers to take away from reading Bellies?

ND: There are two kinds of feedback I’ve had from readers so far that have resonated with me the most. One is from older cishet people who have read the book and said that they connected with it and learned a lot. I think that’s such an amazing thing. It’s scary to be reminded of people’s capacities to learn from fiction, because suddenly you’re strapped on with more responsibility, but it’s incredible to have the potential to foster that sense of empathy. And the second kind is talking to young people, and being told that they read Bellies and felt connected to it, saw themselves in a book in a way they hadn’t before.

The vast differences between those two reactions has shown me that the ways that art interacts with the world are so unpredictable, and I don’t want to be prescriptive with what people find in Bellies. More than anything, I’m just excited to see what people can get out of it.

Bellies by Nicola Dinan is published by Penguin, and is out now.