As his new feature hits cinemas, British-Moroccan director Fyzal Boulifa talks about why the idea that you can only write about your own experience is “a bit of a trap”

Fyzal Boulifa is uncomfortable at what he sees as a certain current in popular culture right now. A few years back, he was forced to field awkward questions from people who couldn’t fathom why Boulifa, a British-Moroccan director born and raised in Leicester, had chosen to make his debut feature about two white women. Now he’s returned with a film set in Morocco, The Damned Don’t Cry, and a whole different raft of assumptions seems sure to follow. (We’re as guilty as the rest of them, as the conversation that follows will reveal.) But Boulifa is suspicious of the idea that there’s something “inherently authentic” in writing your own experience. In fact, he sees the ostensibly well-meaning notion as underpinning a strange state of affairs in which filmmakers of colour, having finally got a seat at the table, are expected to ‘represent’ cultures they may or may not have knowledge about, limiting their scope as storytellers.

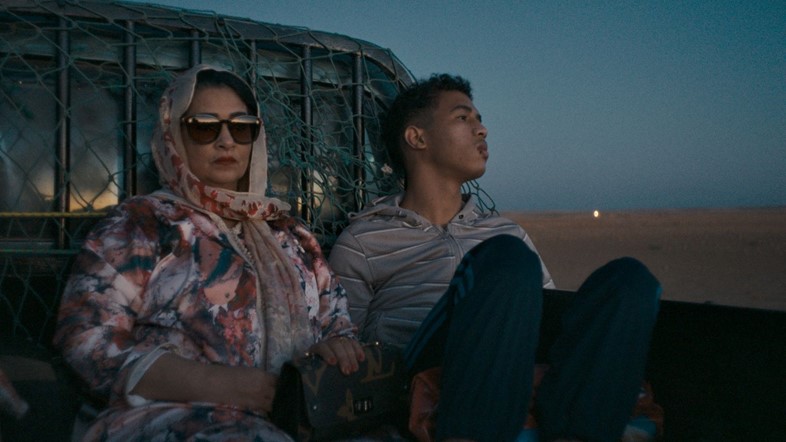

The Damned Don’t Cry resists such easy scrutiny. The story of a mother and her 17-year-old son trying to make ends meet at the edges of Moroccan society, it deftly chronicles its characters’ attempts to twist free of their fate – Fatima-Zahra (Aicha Tebbae), a self-proclaimed ‘modern woman’ scorned by her family for her immodesty, and Selim (Abdellah El Hajjouji), a brooding mother’s boy who takes work for a wealthy Frenchman who has more than just his construction skills on mind. Boulifa uses this modestly scaled melodrama to artfully sketch the ways in which Western materialism rubs unpleasantly along with cultural and religious norms, sex with commerce, class with character, without ever losing sight of his protagonists’ humanity. It’s a fine piece of work from one of the brightest new filmmaking talents in Britain today.

Below, AnOther spoke with Fyzal Boulifa about the making of The Damned Don’t Cry.

Alex Denney: When you were promoting your first feature, Lynn + Lucy, you said that you felt people almost expected you [as an ethnic-minority director] to make something very personal, and you wanted to get away from all that. Was the feeling with this one that maybe you’d bought yourself enough space to tackle something more in that vein?

Fyzal Boulifa: Not really, because I had the script for this before I made Lynn + Lucy. For me it’s a bit of a trap, this idea that you can only write your experience and there’s something inherently authentic in doing that. I think it’s something quite particular to the current moment; we’re seeing it in literature and fine arts as well. If you’re from an ethnic-minority background there’s an expectation, and [while that] can be an important artistic gesture in many cases, not everyone is going to be like that.

AD: I can see how that would be limiting for anyone working as a filmmaker.

FB: I think it’s an unpleasant irony of the situation we’re in: we do have more diverse people who are able to make films, but what they’re able to say is actually becoming more narrow. When I made Lynn + Lucy there was very much this feeling of, “Why has he made a film about two white women in Essex?” There was this weird undercurrent. I also think it’s testament to the fact that class is still the real taboo. We have all these ways of talking about race, almost to the point of fetish I would say, but it’s still very difficult to talk about class in this country. And that was eye-opening for me, because no one made the connection.

AD: Fatima-Zahra is someone who’s spent her life trying to break free of Moroccan society, without ever succeeding. What were your inspirations for the character?

FB: She was inspired by women that I knew, women who were always very well turned-out and careful to project a certain image [of themselves] despite the misery of their everyday realities. I always found that very touching. Fatima-Zahra is kind of a chancer and manipulator on one level but she’s also very childlike and charming; she’s strong but I didn’t want to make her into this western projection of what a feminist should be. And actually she is typical of a lot of Moroccan women of that class in that her dream is to get married. I feel like it’s very incongruous when you see a film from this part of the world and, and …

AD: You feel like they’re playing to a Western audience?

FB: Absolutely. Often there’s an idea in those films that everyone is a Western subject waiting to be liberated. [My film is] a bit more complicated than that, hopefully.

AD: What about Selim? I guess on the face of it you might say he’s a closeted gay young man. But is it also a bit trickier than that?

FB: For me, you can’t necessarily say he’s closeted because it doesn’t make sense for me to say that in a Moroccan context. He definitely has a certain desire, that much is clear, but it was important for me to not give too much of a satisfying expression of that desire in the film.

AD: I was surprised when I learned you had used non-professional actors for the lead roles in the film. Aicha Tebbae has such an old-world glamour about her.

FB: Aicha is from Casablanca; she’s very much working class and she is older than I’d conceived the character as being. When she came in she wasn’t at all glamorous; she really metamorphosed during the process. But she was extremely charming; you noticed her charisma immediately. So we said, “We’re going to absolutely look for a small role for you.” And then I think she clocked that we were looking for someone younger, and she just kept coming back! She came in with, like, hair extensions and had her make-up done professionally. And eventually, I was like, “Maybe there’s something in this.”

AD: How have people responded to these characters on the whole? They are definitely messy, but I found myself really pulling for them.

FB: Honestly, a lot of people don’t like them. [We showed] the film in Palm Springs and had the most underhand comment from the jury. It was like, “Even though we found these characters completely unlikable we accept that the film was challenging us in our prejudices against them.” [Laughs.]. I was like, “Oh my God, that’s so … begrudging!”

The Damned Don’t Cry is out in UK cinemas now.