Screen Shots: in a new series of flash fiction for AnOthermag.com, critic and essayist Philippa Snow looks at the interior lives of female characters on screen.

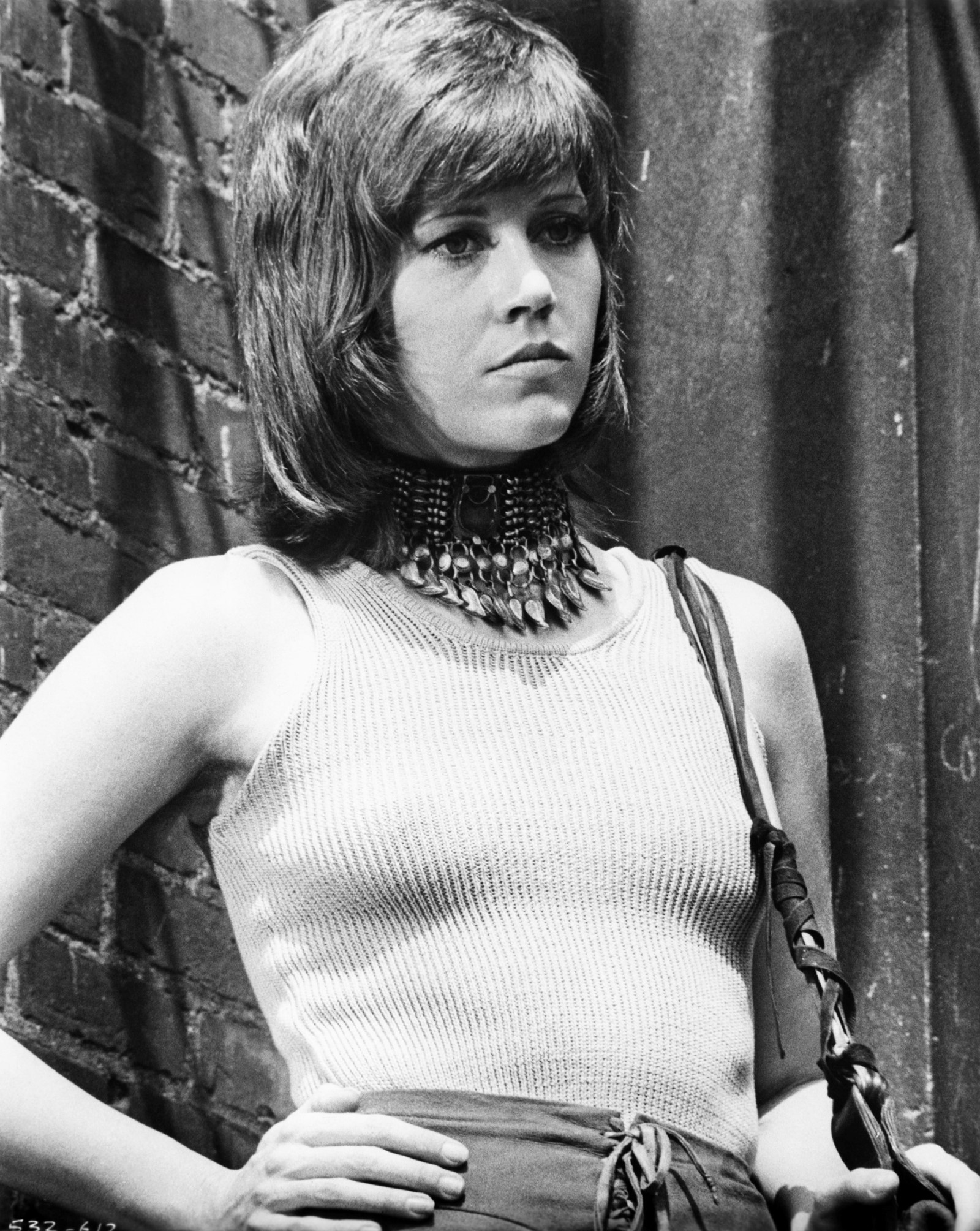

When Bree first cut her hair, she thought it made her look exactly like a boy, a junkie boy, and that was what she liked about it. She began to see it as a challenge to her johns – a challenge to their heterosexuality, or their own inevitable obsession with their heterosexuality, when they took her from behind. She preferred it when they did so that she could not see their faces, and so they could not see hers, not because she cared if they were ugly, but because it left her free to adopt whatever expression she desired. Bree was a call girl, but she was also an actress, and although she liked the former job a lot more than the latter, and she hated to resort to tired clichés, she had to admit that both were fairly similar occupations. Let’s say every trick was an audition, and the role was that of a specific kind of woman: a submissive wife, a schoolgirl, a frightening dominatrix. Then, say each of these auditions had been taped, which in a way they had, since Bree liked to remember them and analyse her performance. If Bree was turned away from her scene partner, i.e. whichever middle-aged man had cast himself that day in the potential movie of her life as the love interest or the husband or the pervert stepfather, it was as if she only had to act a little, as if she were doing a voiceover job or being a stunt double instead of a real actress. Her voice, low and husky and a little boyish in itself, would continue to insist that the man was the best she’d ever had, or that he was so strong and large she couldn’t take it, while her face went slack – went blank as a beautiful mask, smooth as porcelain, still as death. It made her feel powerful to know that she was expending less energy this way, efficient and composed.

“They want a woman,” she had told her therapist once, “and I know I’m good at that. For an hour, I’m the best actress in the world.” Her therapist had done the same thing that he usually did, which was to stay silent until Bree felt pressed enough to fill the time that she kept speaking, offering up more of herself than she’d originally hoped. “What I would really like to do,” she’d added, letting her eyes dart up to the ticking clock, “is be faceless, and be bodiless, and be left alone.” Privately, she wished her therapist would leave her alone, too, despite knowing that – just as the johns paid her – she paid him for his time, hoping for the opportunity to see herself with perfect, pleasing clarity, as if from a God’s eye view. This afternoon, Bree had found herself sitting in line with maybe 20, maybe 30 other women, all entirely silent, clutching headshots and attempting to arrange themselves to look especially pretty, and that session with her therapist had crept back into her mind. A stern person with a clipboard had walked slowly down the line of quiet and compliant women and had commented aloud on their various physical attributes, as if the women were not real, or as if they were nothing other than their faces and their bodies. “Do we want a blonde?” the person had asked no one in particular, moving inexorably along. “Maybe not a blonde. Bad posture. Not a great chin. Lovely eyes.” Bree had wanted to say leave me alone then, as well, but the words jammed in her throat, and so instead she’d thought about the money hanging in the balance and then done the opposite of her deadening move, letting the light rush to her eyes at once the way blood rushes in a headstand.

“Bree was a call girl, but she was also an actress, and although she liked the former job a lot more than the latter, and she hated to resort to tired clichés, she had to admit that both were fairly similar occupations” – Philippa Snow

They did, it turned out, want a blonde; Bree was a brunette. She left feeling faintly violated, which just made her chuckle, darkly – she imagined what the kind of people who believed she needed saving from her other job might say to that. Returning home to her apartment, she slipped easily into her evening ritual of drinking cheap white wine and getting stoned. Being a model or an actress meant rejection; selling sex meant being desired, maybe briefly being loved. It meant offering the best of oneself every time and that best being accepted slavishly and gratefully, in the generous spirit in which it was given. It meant being the best fuck of anybody’s life. How could being cast in a non-speaking role in a commercial, playing at being a wife still but never actually getting to say shit, ever compare? A familiar light-headedness began to descend on her as she smoked, and abruptly she felt moved to sing – a hymn that she remembered from her childhood about gathering together, something about chastening and sinners. It had been a lifetime since she’d thought about this song, and when the words came they came falteringly, slippery enough in her memory that they barely made it through the fog of marijuana to her mouth. The candles on the table flickered in the zephyr of her breath; the refrigerator hummed almost inaudibly. She drummed her fingers softly, keeping time.

Lately, she had begun feeling she was being watched, and to imagine that this feeling had something to do with God benevolently looking over her rather than with a stalker reassured her, even if she did not technically think that there was a God at all. True, there had been phone calls, and there had been letters, too – dirty, threatening letters. Still, everyone said the Lord moved in mysterious ways. Most of all, what stayed with her was the feeling of a shadow in the stairwell of her building, its eyes burning a deep hole into her back. Didn’t that sensation resemble one they had talked about in Sunday school, a million years ago? Finishing what she could remember of the hymn and then coughing a little, she rose slowly to her bare feet, noticing how silent the room was in the immediate aftermath of her performance. That word, ‘performance,’ dogged her lately, just as the idea of being surveilled did. Padding from the kitchen to her bed and climbing underneath the quilt, it struck her suddenly that when she had admitted to her therapist that she wished that she could jettison her body and her face, she’d never once thought about giving up her voice. Maybe this attachment to her ability to express herself – not in character, not with her beauty, not for cash, but sincerely, loudly – helped explain why she had felt the need to sing, even if she happened to be singing to somebody she did not believe in. God, anyway, was most often thought of as a Him, and believing in any man felt like a foolish thing to do. Faking it was better.