Jeremy Allen, who interviewed Birkin at home in Paris for his Serge Gainsbourg memoir, writes a personal tribute to a woman “who made things happen”

Jane Birkin’s death has caused wavelets of grief in her country of birth, though in France where she lived since 1968, the news is more akin to a national disaster. The announcement on Sunday prompted a collective outpouring of sadness, especially on social media where her image has been an omnipresent aide-memoire of vintage 70s chic. With her partner of 11 years, Serge Gainsbourg, she’s become a fixture of idealised fidelity on platforms such as Instagram, in spite of their splitting in 1980. Anyone who has taken more than a cursory interest in the pair knows that the story doesn’t end there.

Birkin first rose to prominence starring in Antonioni’s Blow-Up in 1966. While her appearance was fleeting, she became the first actress to show her pubic hair in a mainstream movie. Plenty more controversy would follow. 1969 cemented her reputation indelibly with a prurient UK media, feigning shock and horror at Je T’Aime… Moi Non Plus, recorded with Gainsbourg and overladen with Birkin’s impassioned breathing. Bans by the BBC and opprobrium from the Vatican helped it on its way to selling six million copies, and a coveted No 1 in Britain.

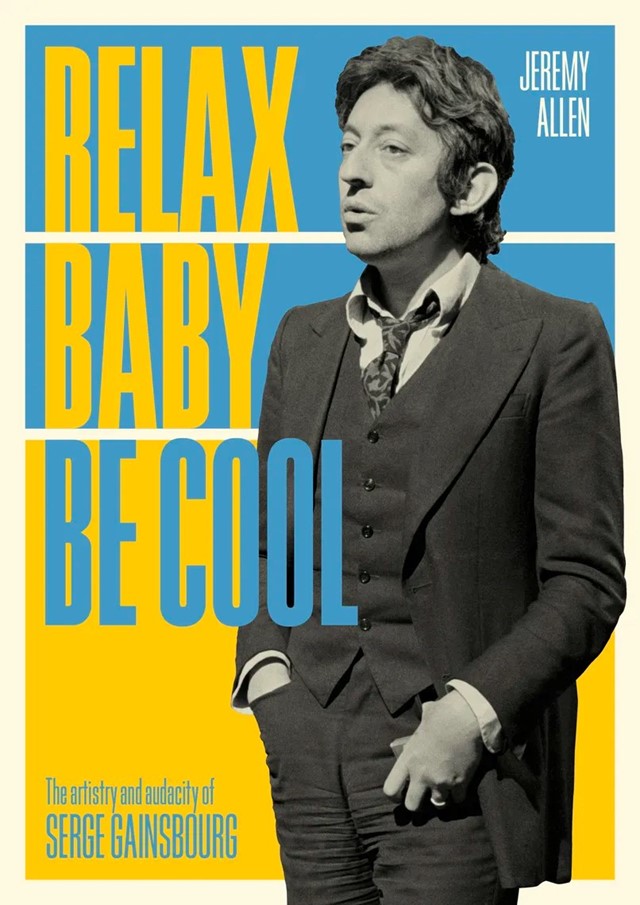

I met Jane Birkin some 50 years later, at her home in Paris at the tail-end of winter 2019, when I was working on my book Relax Baby Be Cool: The Artistry and Audacity of Serge Gainsbourg. Although she still sang the songs Gainsbourg had written for her, she’d more or less stepped away from talking about the man with whom she’d come to be inextricably linked. It was my good luck that she’d got the idea into her head that I was a translator, and her bad luck that I have no such talent. She informed me her final mission in life was to get Gainsbourg’s chansons translated into English, an undertaking her nephew Anno Birkin – son of her brother, the filmmaker Andrew Birkin – had attempted before he was killed in a car accident just shy of his 21st birthday.

Jane had tragically lost her own daughter, Kate Barry, to suspected suicide in 2013. A large picture of Kate hung behind her in her black-clad apartment in the sixth arrondissement of Paris where I joined her for coffee. I sensed she was still mourning, and I’m doubtful she ever stopped. As we exchanged pleasantries as a means of introducing ourselves, she wanted to know all about my son, Jean, who was soon to turn two. Her warmth was genuine and unmistakable.

A little later, I mentioned that a few nights earlier I’d seen her cameo in offbeat South Korean director Hong Sang-Soo’s Nobody's Daughter Haewon, which set her off talking enthusiastically about cinema which she undoubtedly lived and breathed. Living a stone’s throw from the Église Saint-Sulpice, she regularly attended the famous old arthouse cinemas of the Latin Quarter incognito, watching old movies and the latest releases. She was very much looking forward to Kore-eda’s Shoplifters; she had recently seen The Favourite and confessed, a little sheepishly, to being a little overwhelmed by “all the lesbians”. It was a surprise admission from a singer and actress who regularly broke taboos and jumped into bed with Brigitte Bardot in Roger Vadim’s 1973 Don Juan, Or If Don Juan Were a Woman.

As for Je T’Aime, she told me that a London cabbie had once gone into graphic detail about siring a number of children listening to that record while she sat in the back (a story she recounted on the BBC, ironically getting herself banned once again). Another story from shortly after Gainsbourg’s death involved a callous British tabloid journalist asking her: “Sung any dirty songs lately, Jane?” It was a comment that so incensed her that she petitioned Mitterrand, Chirac, Bardot, Godard, Saint Laurent et al, to write a few sentences explaining exactly what Gainsbourg meant to them, before getting them published in a newspaper in England. Her love for him appeared undiminished, despite his violence towards her at the end of their relationship when his alcoholism began to take hold. I’ll not forget her introducing me to Raccrochez C’est Une Horreur on her phone, a skit Gainsbourg had written for her in the mid-70s for TV, laughing through floods of tears as it played.

Fiercely protective of his legacy, she was dismissive of her own, having once told the Guardian: “He was a great man. I was just pretty.” When I’d try to talk to her about her impressive filmography, she derisively brought up her “silly films” from the early 70s. In actuality, she was a natural actor with exquisite timing who was more famous than her partner throughout the 1970s, before he made a seismic commercial breakthrough with his 1979 reggae album Aux Armes Et Caetera.

Once she left Gainsbourg for the French director Jacques Doillon, it coincided with her being taken more seriously as an actress and cultural figure. Being asked to design Hermès’ Birkin bag in 1983 enhanced her reputation no end, although she had already carved out a niche as a bohemian fashion icon, androgynous in white t-shirt and jeans with a wicker basket as accoutrement – a breath of fresh air in early 70s France. Another elevation occurred with the patronage of legendary nouvelle vague auteur Agnès Varda, who made Jane B Par Agnès V to mark Birkin turning 40. While the French are notoriously slow to embrace outsiders, Birkin was taken to the public’s bosom largely because she was so likeable.

Her pop career too was more singularly successful than she’d ever let on. Admittedly it had begun thanks to Gainsbourg, though his masterpiece Histoire de Melody Nelson couldn’t have happened without her (Melody was a malapropism of her middle name, Mallory, with the 15-year-old schoolgirl protagonist modelled on his favourite “petite anglaise”). Solo albums of note include 1973’s delightful Di Doo Dah, again with Gainsbourg and Melody Nelson’s arranger Jean-Claude Vannier, and 1990’s Amours Des Feintes, the last songs Gainsbourg wrote. She made fine albums without him too, namely the largely self-penned Enfants d'hiver from 2008, and arguably her personal piece-de-resistance Oh! Pardon Tu Dormais…, from 2020, with the peerless Étienne Daho.

Towards the end of our interview, Birkin went out of her way to help facilitate my book further – something she didn’t need to do. She scribbled down her daughter Charlotte’s email address in pencil – which understandably thrilled me – and she also introduced me to Gainsbourg’s oldest sister, Jacqueline Ginsburg, 93 at the time and still living on the Avenue Bugeaud where the Ginsburg family had settled after the trauma of the Nazi Occupation. I visited Jacqueline at home, filled with artefacts, paintings and mementos of her brother, and got to hear first-hand their experiences of war and childhood. I spoke to Charlotte Gainsbourg, too, on the phone from New York. Both interviews added a wealth of colour to a biography that wouldn’t have been possible without Jane. Self-effacing and always prone to deferring the credit to somebody else, I was struck by her kindness and became very aware of somebody who made things happen.

Jeremy Allen is the author of Relax Baby Be Cool: The Artistry And Audacity Of Serge Gainsbourg.