Despite some stiff competition, I can handily say that Henry Hoke’s Open Throat is the best genderqueer mountain lion novel of the year. It might also be the best novel of the year. Written from the perspective of a puma (who uses they/them pronouns) struggling to survive in the foothills under the Hollywood sign and in the animal’s distinct grasp of English, Open Throat’s unusual narrative flows like the best poetry. It’s a concept that could go awry in the wrong hands but under Hoke’s witty, empathetic control it is a remarkable feat of fiction, elegantly weaving together ideas of queerness and transness, of the climate crisis, of the corrosivity of mankind, with an uncommon subtlety. Hoke, who was born and raised in Virginia, spent a decade living in LA and became enamoured with P-22, a mountain lion that crisscrossed the city and turned into a local celebrity.

In the offices of his publisher, Picador, Hoke spoke with fondness for his lion and P-22 as we discussed Open Throat, queerness in the animal kingdom and whether he’s written a furry novel.

Patrick Sproull: What was your relationship to P-22 and how did they come to inspire Open Throat?

Henry Hoke: The area where I spent the most time in LA was this area of Los Feliz, which was at the foot of the mountain up to the observatory in Griffith Park. I would spend a lot of time navigating that space and feeling that strangeness of LA, of the natural and the urban. A year after moving to that neighbourhood was when P-22 was spotted. It was already a mythical presence and I was always hoping I encountered that cat. There were news stories about how P-22 had been living under a house in a crawlspace for a long time and I thought it was amazing that the lion had been blessing this random house. That was the beginning of my obsession and I would check up on it and think maybe I’d see it or know when it was in the neighbourhood.

PS: Did you ever see them?

HH: I never personally encountered P-22. There were sightings up until I sold the book early last year and the cat was spotted in Silver Lake, which was a whole different neighbourhood. That’s where I was staying so I was like, I’m going to run into the cat. I looked out of my Airbnb and saw a large feline shape in the corner of the yard. My heart stopped, I was like … this is it. When a light hit it, it was just a sculpture of a cat, but that sort of haunting was always there. It never occurred to me to write in the voice until I moved back to New York right before Covid. That was the only way I could write about LA, to write not as me. I had to be my own version of this wildcat in a city.

PS: There’s a documentary from a couple of years ago by Andrea Arnold called Cow about the life of a dairy cow. Every time she screened it, she would break down in tears because she had become so attached to this cow. Both P-22 and the lion in Open Throat have had hard existences too. Did you feel that kind of attachment?

HH: When I was writing it and inhabiting it, it was a joy and it was painful but it felt real. I joke that it’s more of a memoir than my memoir because it’s just how I was feeling about so much of LA, from everything about that clash between the natural and the urban, the normalcy and the apocalyptic, the inequality and the numbness of that space. A lot of those things were coming up in how I was writing this so I felt very, very connected to the lion, almost as if I was writing it as myself. The plot was hard and tragic and tough but I wanted a real story here.

“That was the only way I could write about LA, to write not as me. I had to be my own version of this wildcat in a city” – Henry Hoke

PS: The lion has an interesting journey with their gender identity and queerness. Gay and queer people have always danced with animal iconography – otters, cubs, bears, pup play – and there’s a line that stood out to me, when the lion describes themself as “a person in cat suit”. Have you written the great furry novel?

HH: Well, it hit me later. I was like, ‘Oh my god, is this a furry novel?’ I made a joke that there was the viral New Yorker short story, Cat Person, so I’m writing Person Cat. It’s a cat that’s dealing with people so much it’s becoming one in all the worst and best ways.

I want to believe we can move towards an overarching genderqueer future for all of us because I think that’s the truth of humanity. But with animals, they don’t play by our rules nor do they need to. Everything that’s been mapped onto them since time immemorial, of the alpha, isn’t applicable or real in the animal world. I thought, let’s play with what that offers, and I see that in the signifiers of the gay community and the, uh, furries. I’m not personally a furry but I see it. In the end, I would love this book to appeal to kids who just want to read an animal voice and then suddenly read the most fucked-up book ever and realise there’s something they couldn’t imagine before. I welcome furry readers, I welcome people who’ve never heard of furry readers, but I want there to be the great furry novel for the actual furry community.

PS: Where did the novel’s queerness come from?

HH: I am very interested in exploring the interiority of queerness in a way that isn’t monolithic because that’s my life’s journey. I knew from the beginning that my cat was not going to be mapped onto human sexuality. I think the journey to being seen as a goddess, to being gendered ‘she’, it fits this lion. To me, the excitement of genderqueerness and transness and opening up your identity is that we are beyond the things that have hurt us and oppressed us our whole lives, and that’s true of this lion. I don’t know if I could write a queerer book than this.

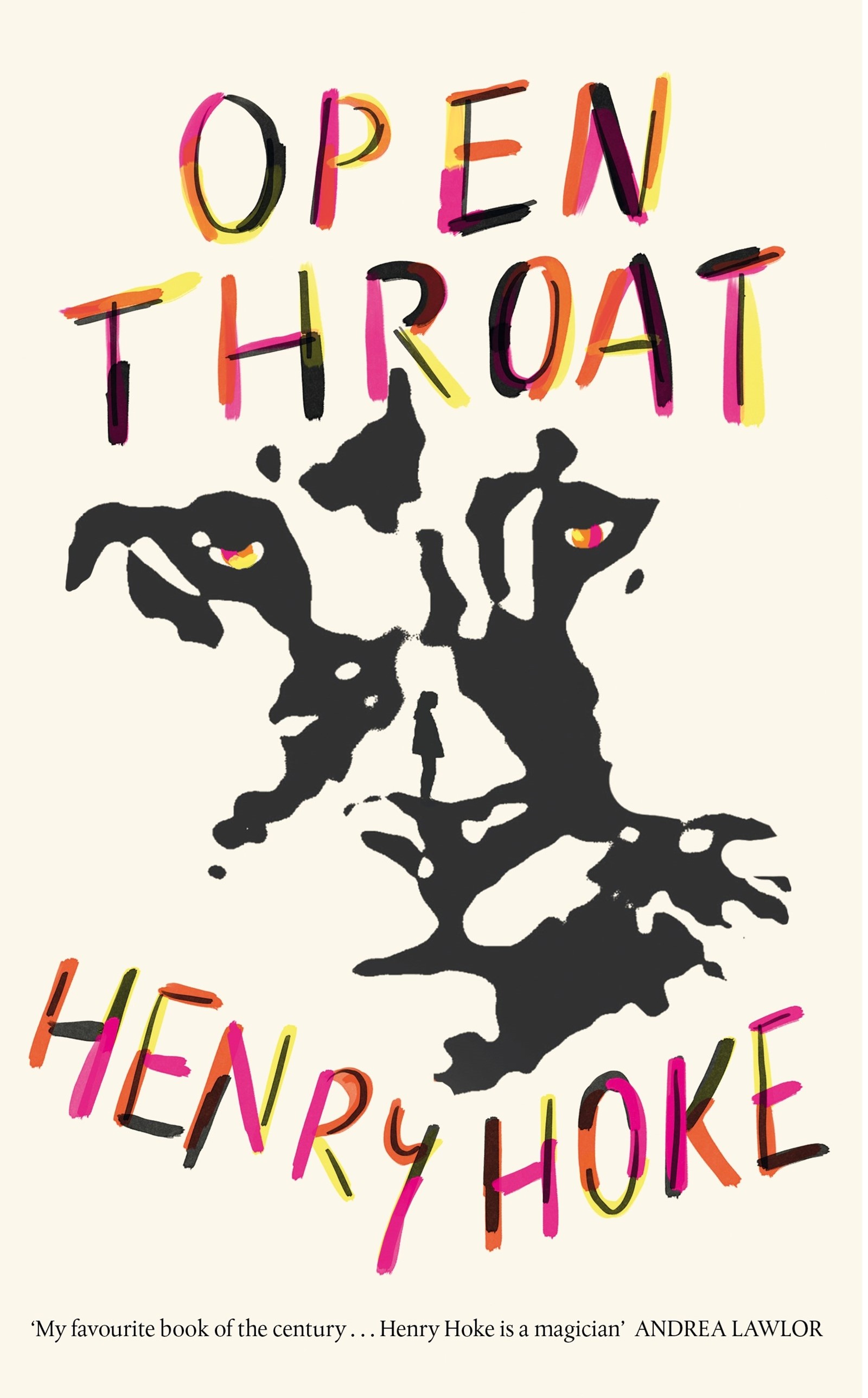

Open Throat by Henry Hoke is published by Picador and is out now.