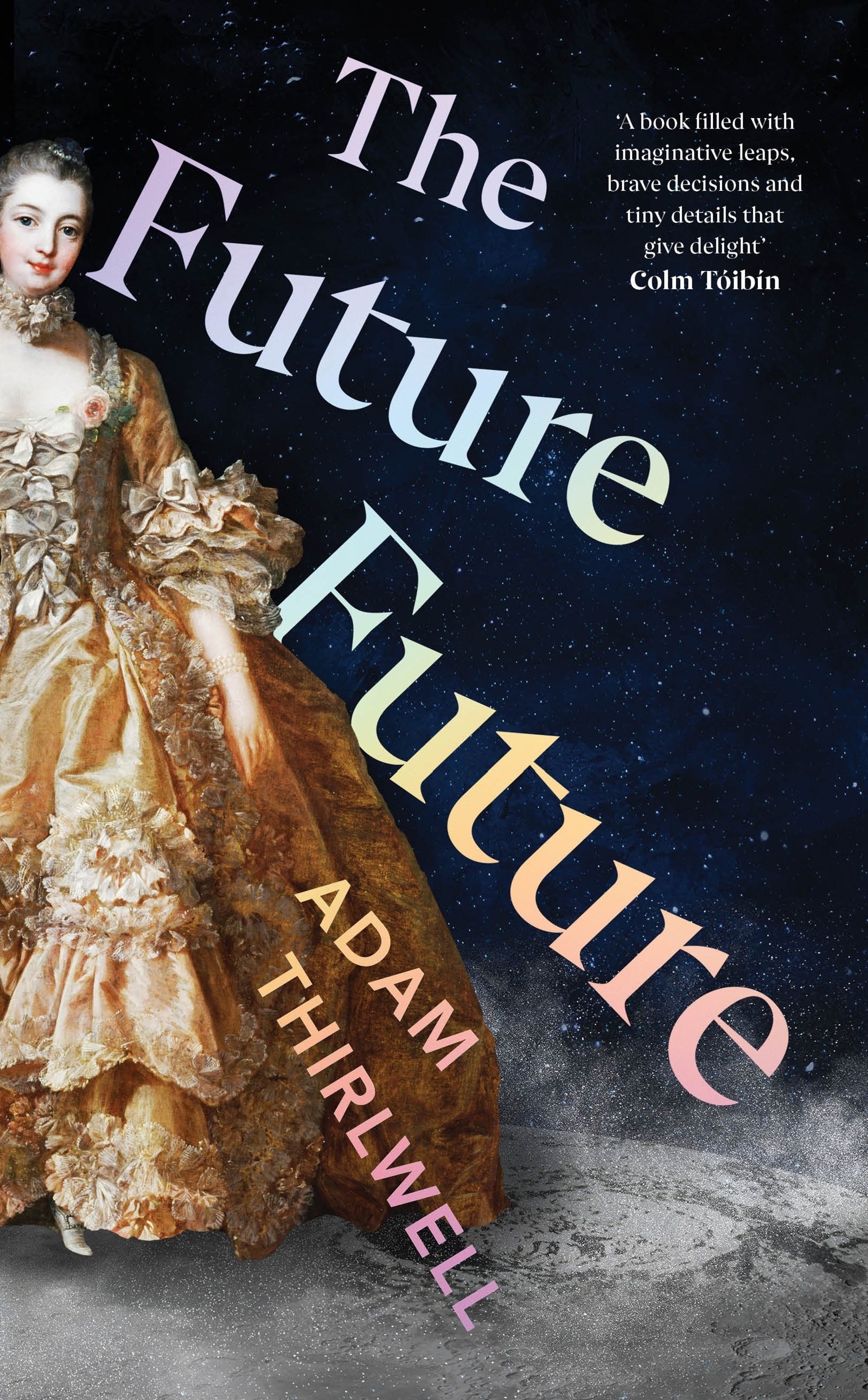

18-year-old Celine is being trolled by an anonymous group of men. They are publishing false stories about her sex life, besmirching her high society reputation with spectacular lies that are greedily consumed as entertainment. Despite these eerily familiar circumstances (and the book’s title), The Future Future, British author Adam Thirlwell’s fourth novel, is not set in the present day but in late 18th-century Paris. Beginning at this precipitous juncture of social and political revolution, we follow Celine through middle age, criss-crossing the globe (and occasionally beyond) as she navigates densely woven power structures to reclaim control of her life, witnessing firsthand the death of one age and the birth of another.

In his typically bold style, Thirlwell subverts the traditions of the historical novel with The Future Future. Deliberately anachronistic phrases give the sense of time being compressed: a writer complains about his work being “stuck in development”, while a stalling party is likened to the nervous energy that precedes a conference call. As in previous works, the full range of Thirlwell’s intellectual promiscuity abounds, with philosophy, language, science and anthropology coalescing into the book’s utopian climax.

Fittingly, Thirlwell is joined by Serpentine gallery director Hans Ulrich Obrist, another polymath, to discuss his new book, its implications for the historical genre and the future of literature more generally.

Finn Blythe: In many of your previous works, time is a fluid, slippery thing. So I thought I would start by asking why you chose to situate this story in the time and place that you did?

Adam Thirlwell: The novel is ironically set in the past, in late 18th century Paris, but also across the globe. That was partly a way into the present, a moment where a recognisably modern moment was taking shape. I guess it was a mixture of the sudden predominance of writing and information media, coupled with the proliferation of technologies to reduce the distance that came from colonisation. So the idea was that whole areas were suddenly coming into contact with other areas and power was being exercised.

FB: Did it involve a lot of research?

AT: I started reading a lot about this period, it’s always interested me, but I grew up with an absolute avant-garde hatred of historical fiction. It seemed like the lowest kind of fiction you could write. So to discover myself thinking, ‘Oh God, I’m about to write a historical novel’, was slightly traumatic. But one way into it was to think, ‘Well, there are these conventions within the historical novel and you don’t need to observe them’. So often there’s a lot of policing, where someone will say, “They’ve used this word and in 1774 – this was not actually used.”

FB: Like fascism, for example.

AT: Yeah, so fascism was a deliberate way of collapsing the timeframe – essentially it’s about power.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: It’s interesting, I came across this piece in The New Yorker, On Killing Charles Dickens by Zadie Smith. She talks about having never imagined writing a historical novel, saying she even left England because she didn’t want to write one. She’s convinced that any writer who lives in England for any length of time, sooner or later will find themselves writing a historical novel, whether they want to or not. She talks of the English being “constitutionally mesmerised by the past”. So this leads to a couple of questions: has it been an excruciating period of reading? Secondly, are there any historical novels of the recent past that you find inspiring?

“I grew up with an absolute avant-garde hatred of historical fiction. It seemed like the lowest kind of fiction you could write” – Adam Thirlwell

AT: I think there’s definitely something in English literary culture that seems to value the historical novel, but often in a very old-fashioned way, which seems to simply be propping up a power structure, repeating a national story. There’s this policing where you’re not allowed to make anything counterfactual, and if you use a real person you mustn’t go against anything they might have done. So essentially historical fiction and actual history are very closely aligned.

And there’s also the question of: what style are you allowed? Are you meant to always pastiche the style of that particular period, or can you write in a different way? The historical novel comes from the 19th-century era of nation-building and nationalist politics. So people like Walter Scott or Alessandro Manzoni, they’re writing these novels to essentially ground a sense of historical identity, often for European nation states. And that version was what I really disliked. I think the one English historical novel I really concentrated on was Orlando by Virginia Woolf. As well as having this extraordinary play with gender, it also has this extraordinary play with time because it’s basically saying the same person can stay the same over a huge time span.

HUO: I was very intrigued the other day on the phone, you said that the visual artist Philippe Parreno was an inspiration. Obviously, his work has a lot to do with time and he always says that art history hasn’t talked enough about time or space.

AT: One of the reasons I think I ended up writing a historical novel was that I wanted to write precisely about a long passage of time. My novels up to that point had been a year in someone’s life, they were quite tight. I was very interested in how you balance timeframes inside a book with the time it takes to read the book. So this idea of tempo that Phillipe deals with in the exhibition format – and something you’d previously said about a book being a portable exhibition – were deeply in my head. If a book is an exhibition, how could you vary the time frames you encounter in the same way Phillipe does in an exhibition?

FB: The forest as a place of healing and reflection routinely punctuates this story. Could you speak about that?

AT: I was reading a lot of anthropology while writing this book, people like [Eduardo] Viveiros de Castro and Philippe Descola. I guess it goes back to this idea of how you write the ‘inhuman novel’ or the ‘non-human perspective novel’. I wanted the forest to be a character and I think I’d been really interested in the way Descola and de Castro talked about anthropomorphism, how it’s only a very specific European culture that looks down on it while so many other cultures see it as an entirely natural way to think. The other day I was reading a relatively new book by Paul B Preciado, Dysphoria Mundi. Preciado says there are three current denials that conservatism is based on. There’s climate denial. There’s a denial of colonisation and its effects. And there’s the denial of gender and gender fluidity. That trio is actually very pertinent to this book, which works on undoing those three denials.

“I suppose the whole question of who is allowed to speak for whom is central to this book and essential to how, at the moment, all literature is being talked about” – Adam Thirlwell

FB: This is very much a book about the female experience, and includes visceral descriptions of pregnancy. How did you position yourself to write from this perspective?

AT: I suppose the whole question of who is allowed to speak for whom is central to this book and essential to how, at the moment, all literature is being talked about. So I knew this would have to be something I took very carefully. In terms of Celine’s physical experience, I was very sure that there wouldn’t need to be any sex scenes. In this novel about someone who’s being pornographically described, I was very sure that I didn’t want to in any way compete with that, and that her sense of privacy had to be maintained. But I also knew that there’s a difference between having a body and being a body, that crucial distinction between what it feels like to be a man operating in the world versus a woman. I felt like it had to be embodied in some way because it was so important to her sense of self. And so obviously, you do a huge amount of talking with friends, but this novel is about all questions of representation. So how would it be okay for a male writer to imagine the female experience, but also in the conventions of science fiction, how do we imagine what an alien might say? So this novel was a constant game with the limits of representation and the constructions of otherness.

HUO: I wanted to ask you about video games in relation to the future of literature. Right now, a lot of my friends in music really dream of working with video games. Is that form of worldbuilding of interest to you?

AT: It’s the worldbuilding that most fascinates me. More and more, I see novels and video games trying to create a world for someone to enter. It’s a bit like what Dominique [Gonzalez-Foerster] said about an exhibition being like a park, and I think that idea of the park was also very important to this book, a space into which someone can wander. What would both give me huge anxiety but is very exciting with video games is precisely that: the player has a huge amount of control and freedom within that landscape or narrative you have created. For me, the novel is still sadly a genre of control. However much a novelist might try and gesture at giving up control, it’s generally just gestural. In the end, the moves have been plotted and the reader can essentially go only in one way.

How do I see the future? I don’t know. This book was obviously written in a very traumatic historical moment about what the future might be; it’s clearly a reaction to Brexit and Trump, however obliquely. Another word we always use is utopian. I’ve always had utopian characters, whether in my first novel with this polyamorous throuple trying to change relations but often slightly losing. I felt it was important for there to be hope in this book; there is a utopian aspect in its trying to imagine different forms of relation. For all the grief at the current situation, I think it’s interesting to see a kind of resistance, however small scale.

HUO: And hope.

AT: Yes. And hope.

The Future Future by Adam Thirlwell is published by Jonathan Cape and is out now.