Here are five lessons from Alison and Peter Smithson’s new brutalist country house Upper Lawn, from submitting to the seasons to having a climate-proof home

Pioneering architects Alison and Peter Smithson were instrumental in shaping the landscape of new brutalism in Britain. Amalgamating the language of modernism versed by Mies van der Rohe with their own unique flare for pared-back finishes and raw, construction-defined forms, the duo were the minds behind a number of pivotal buildings of the era, including the Robin Hood Gardens housing complex in Poplar, east London and the Grade ll* listed Smithdon High School in Hunstanton, Norfolk.

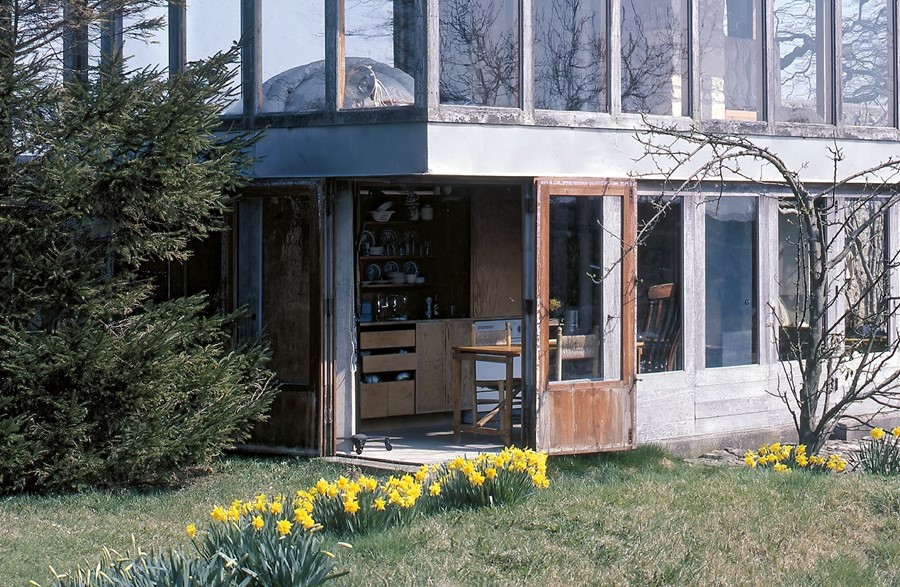

The Smithsons were explorers, in search of connection and honesty through material transparency and experiential observation, and it was one of their own homes that became their most fruitful frontier of investigation. Newly published by Mack, Upper Lawn, Solar Pavilion revisits a small book Alison created with Spanish architect Enric Miralles in 1986, that documented the construction and life of the Smithson family’s rural sanctuary and architectural testing ground. Born of the remains of a farm demolished on the estate of the former Fonthill Abbey, their ode the English folly became a place to form and trial various aspects of their new brutalist approach.

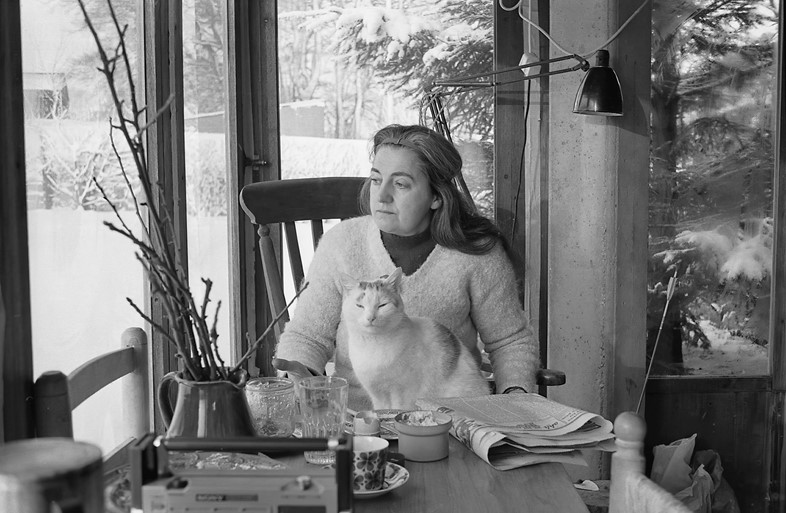

The reimagined and redesigned publication contains all of the many diary entries, photographs, drawings, and references collated by Alison and Miralles, alongside extensive new materials from the Smithson archive. With a tender and unpretentious poetry reflective of their architectural vernacular, the diary entries in the book narrate the living and learnings of life at Upper Lawn for Alison, Peter, their three children and their cat Snuff.

Below, we give you five lessons to learn from Upper Lawn.

1. Submit to the seasons, and admit to their melancholy

As wind speeds quicken and sunlight falters, nature’s transitions from sunshine to snow can see the serenity of the English countryside replaced with solitude. As stated by Peter in the book’s 1985 introduction, those choosing to reside in the countryside must become familiar with the beauty of an annual carousel of feeling. “Upper Lawn was placed in an 18th-century English landscape with the conscious intention of enjoying its pleasure, its history, of submitting to its seasons, admitting to the melancholy that seasons and quietness can entrain.”

2. Establish a territory under one’s own control

Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich’s Barcelona Pavilion is referenced significantly by the Smithsons. Recognising this icon of modernist architecture as the physical manifestation of an idea, Peter concludes that Upper Lawn is the fourth generation of the movement’s own attempt at creating a place of withdrawal. “If we were to try and offer a ‘working example’ for the late 20th century, or demonstrate the possibility of such a place by a ‘presence’ equivalent to the Barcelona Pavilion, what would be its nature? There is no doubt that the ‘poetic’ in Barcelona and the ‘practical’ in Berlin were different faces of the same impulse. The impulse now is to establish a territory under one’s own control.”

3. Find pleasure in reprise

In August 1976, reflecting on the documentation of Upper Lawn, Peter wrote, “The photographs of this small building are intended to show how familiar to us are the pleasures of repetition: the farmyard’s boards, blocks, and corrugated asbestos roof the repeated trees on the hillside beyond the view out to a landscape seen as a series of regular-sized pictures – as from a stoa the simplicity and elegance of repeated elements which combine into a structure the repetition of dimension showing up subtle differences of material, making those differences pleasurable. Such a gentle building is capable of responding in a thousand ways ... to weather ... to trees growing and dying ... to the events of a family life … but that is a different story.”

4. Bring the outside in and the inside out

Having built their “climate house” as an experiment – “to find out what it is like to live in a house in England all the year round” – the Smithsons became accustomed to the choreography of the elements. In July 1963, Alison wrote, “In the country, particularly in our hillcrest situation, wind conditions work against any free open-or-closed idea. This we also found true of the Aalto Maison Carré where our whole tour was conducted to the accompaniment of slamming doors. To make a ‘climate house’ workable as an everyday proposition and not as a game it would have to be openable at a touch as Japanese screens indeed are. The aluminium cladding has stayed bright in the unpolluted atmosphere. But in gales the crack of the sheeting recalls the descriptions of noises on big sailing ships.”

5. Keep a diary about goings-on at the house

The only constant in the period of Upper Lawn’s existence documented between 1962 and 1982 is change. Month by month, the diary written by Alison records each event: the growth and demise of shrubs, trees and bushes. The bringing and killing of mice by the cat. The mishappenings of hedgehogs and badgers with unfortunate ends, and the construction and reduction of architectural features of the folly. She illustrates the changing of the seasons with rigorous weather reporting, while noting the adaptations of the intended use of materials repurposed by her children as makeshift playground equipment. Conceived as a practical experiment – a playground for architects with ideas to test – it’s no surprise that things rarely stayed the same at Upper Lawn, and a testament to the success of those that did.

Upper Lawn, Solar Pavilion by Alison and Peter Smithson is published by Mack and is out now.