The title of Diarmuid Hester’s book Nothing Ever Just Disappears isn’t originally his. It previously belonged to a short story by the American writer Sam D’Allesandro. D’Allesandro died of Aids in the late 1980s and the imprint of his literary work was largely forgotten in time, but not by Hester. Here, the Irish radical historian and scholar has respectfully, tenderly repurposed D’Allesandro’s work as an act of remembrance, to both D’Allesandro and the myriad queer figures whose presence has been erased from existence. It is that erasure, of their lives and influence, that Hester seeks to counteract in Nothing Ever Just Disappears.

Hester is eager to clarify that Nothing Ever Just Disappears is “not a comprehensive history of queer culture in the 20th century”, and within just a few pages, it’s clear that Hester has crafted a thoroughly original and playful new chronicle of queer history. Selecting a handful of queer figures - from EM Forster through Josephine Baker to Claude Cahun and Kevin Killian – Hester writes on what we mean when we talk about gay figures queering spaces and the lasting impact of displacement. He approaches these historical players through their home turf – Forster’s Cambridge, for example, where Hester currently resides; or Baker’s Paris; Cahun’s Jersey; Killian’s San Francisco – and questions how their locales shaped their work and their personhood.

Here, AnOther speaks to Diarmuid Hester about his new queer history, researching during the pandemic and approaching his subjects like friends.

Patrick Sproull: You bookend Nothing Ever Just Disappears writing about Derek Jarman and Prospect Cottage. Why was that your starting point?

Diarmuid Hester: The idea for the book emerged from that moment in January 2020 when Derek Jarman’s home – Prospect Cottage in Dungeness – went up for sale. It’s a very interesting place and it has this really important role in the development of queer politics and queer art in Britain. It’s really, really important because Jarman was an Aids activist but also because he wrote about it so evocatively in Modern Nature. When he died it was taken care of by his partner, Keith Collins, and when Keith died the cottage was going to be sold and there was this moment when it could have entered into the hands of a private owner. In order to stop that from happening there was this huge crowdfunding campaign and they raised £3.5m to buy the cottage, to maintain it in perpetuity.

I remember reading a piece by Luke Turner in The Guardian about how if it were to be saved, which it eventually was, it would be the first radical queer heritage site. I don’t think that’s necessarily true given the research I subsequently did but it was quite a powerful description. I thought this was a really interesting place to start and to think about the importance of queer spaces and why people were so quick to leap to Prospect Cottage’s aid.

“The idea of home is such a complicated notion for queer people and why the majority of people I talk about in the book make lives and build worlds far away from where they grew up” – Diarmuid Hester

PS: I read an interview you did around the release of Wrong, your critical biography of Dennis Cooper, where you said that when writing biographies of queer people it’s important to frame them beyond conventional narratives like their family and their upbringing. Is that how you approached Nothing Ever Just Disappears?

DH: This was something I learned while writing Wrong, I was trying to think about where I sat as an interpreter of somebody’s life. It was made more immediately, ethically necessary to think about that when that person is alive because you run the risk of offending somebody who has, in this case, been very supportive. It’s about thinking where the limits of your interpretation lie and negotiating between two people, and having the book attest to that relationship. In Wrong, the biographical element was Dennis’ story and his life, and the critical part was where I was interpreting his work and going on flights of theoretical or scholarly fancy (some of which he didn’t really agree with, which is fine).

When I started to write this book I thought, what am I going to allow myself to do? And where do the limits lie between their life and mine? I think this negotiation between them and us, between the other and the self, comes down to this idea of friendship. Friendship is a really important idea for me and one that runs through my writing and scholarship and the way I approach historical subjects.

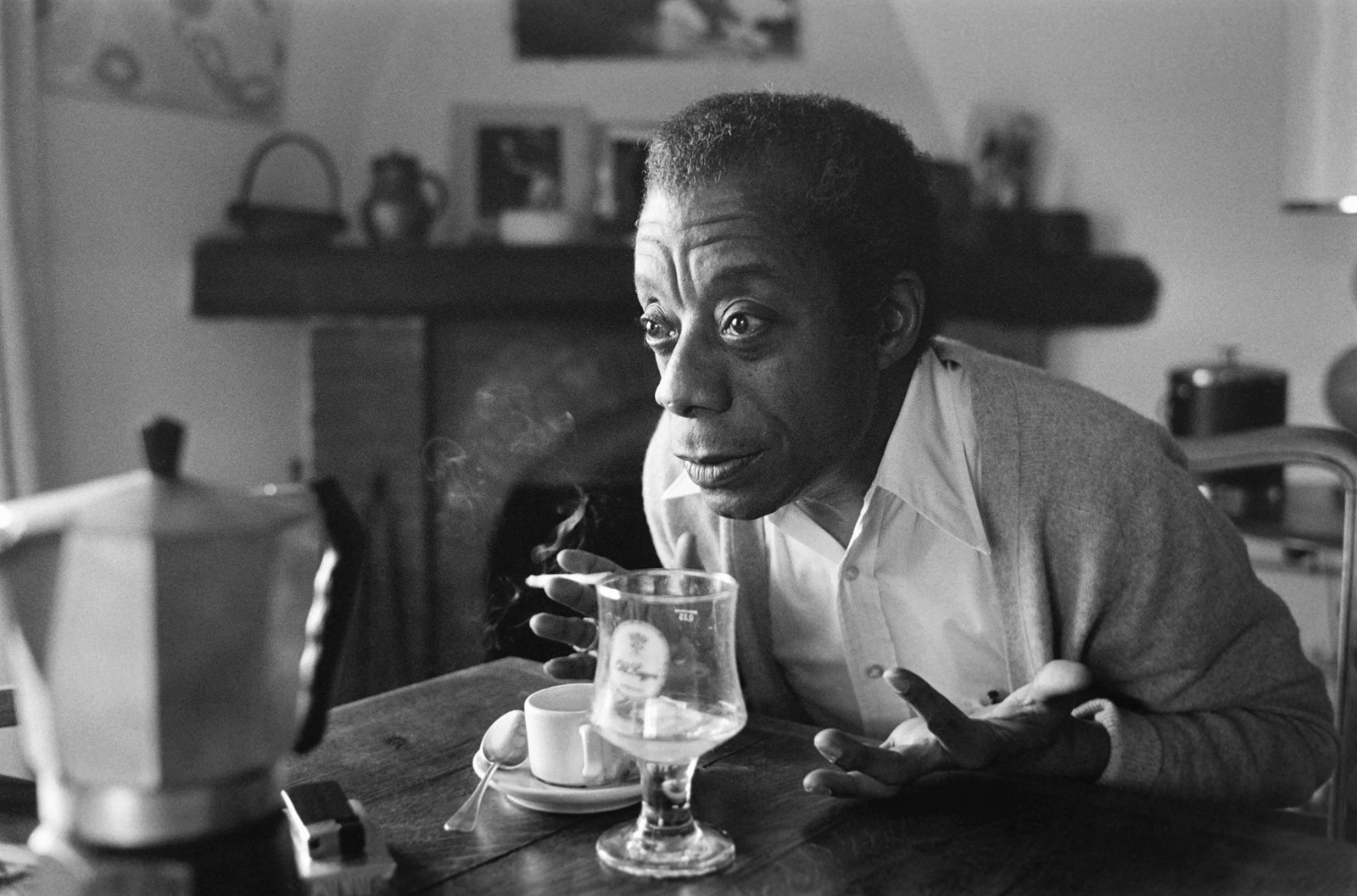

PS: I appreciated how you had a loving but critical perspective on these figures, in particular James Baldwin. Was that something you developed through writing the book and did it challenge your assumptions on him and other figures?

DH: Yeah. I have loved James Baldwin’s writing for a very long time. I have disagreements with him – not that he ever knew that – and problems with some of the framing in his work. You know, queer history is not an institution, although apparently we have Queer Britain, a museum in London. But it’s not an establishment, it’s not an institutional thing, so we go in search of queer stories we can draw upon and be proud of. I think there’s a temptation to look back at the past and romanticise – when it comes to someone like Baldwin, effacing the more difficult, disappointing moments of his life and his work really does him a disservice, and it’s historically inaccurate.

I wanted to dig into the shame that was a fundamental part of his upbringing. Even though he wrote Giovanni’s Room, which is this gay classic, it was all about shame, and in writing it, it’s not like he exorcised his demons. His shame was there throughout his life despite the fact he was this powerful orator with a strong moral and ethical compass. I connect with Baldwin so much. In spite of the huge difference between where we grew up, we had a similar Christian, conservative background.

PS: What was it like writing and researching a book about place during the pandemic?

DH: I don’t think you can dissociate the project and my thinking about the book from the fact that for many months we weren’t able to go anywhere. But that feeling of not being able to access a particular place or feeling locked out is something I’ve been quite familiar with. Maybe a lot of queer people are familiar with that as well; there are a lot of spaces that are heavily coded as heterosexual or heterosexist. It’s why gay bars exist. I think that reluctance to enter certain spaces overlaps with the feeling of displacement that’s very important in the book.

The idea of home is such a complicated notion for queer people and why the majority of people I talk about in the book make lives and build worlds far away from where they grew up. They flee homophobia and other kinds of oppression in order to find a home elsewhere. I think that’s something hopeful about the book. In spite of this threat to traditional queer spaces – the report that showed in 2017 that in the decade before 58 per cent of queer night venues closed down – the book is hopeful about how home is a very complicated idea and you will feel displaced, but there are other places where you can make home. There are other places where you can make a community and you can feel accepted.

Nothing Ever Just Disappears by Diarmuid Hester is published by Allen Lane and is out now.