Daniel Lopatin began his music career in an emphatically underground fashion, releasing limited-run cassette tapes and CD-Rs of synth-based ambient, drone, and noise music in the 2000s. On paper, the avant-garde electronic musician was an unlikely candidate to influence an entire subgenre of electronic music (Vaporwave), soundtrack an Adam Sandler film (Uncut Gems), executive produce a platinum-certified album (The Weeknd’s Dawn FM), perform on the Chanel runway, and serve as the musical director of The Weeknd’s Super Bowl halftime show. It’s a remarkable career trajectory, but what if things had turned out differently? What if Lopatin had taken one of the many other paths that were illuminated to him early into his young adulthood? What might his music sound like today?

Lopatin explores these questions on Again, his newest album as Oneohtrix Point Never. Music, memory, and fantasy intersect as Lopatin imagines a hypothetical collaboration between his present self and his past, young adult self. The result is a straightforwardly musical and satisfyingly emotional record that adds post-rock, prog-rock, and orchestral composition to the OPN sound palette. In real life, Lopatin’s early twenties were where many of his formative musical experiences took place, surrounded by exciting art and interesting people after leaving his home state of Massachusetts behind. Some of Lopatin’s collaborators on Again were influential during this period of his life, such as the experimental rock musicians Xiu Xiu and Jim O’Rourke, and former Sonic Youth guitarist Lee Ranaldo. Among these human collaborators are some inorganic ones too: the artificial-intelligence tools OpenAI Jukebox, Adobe Enhanced Speech, and the Riffusion neural network.

When he spoke to us about Again over Zoom, the usually New York City-based Lopatin was in Los Angeles, sitting on a porch smoking a cigarette and batting away mosquitoes during a break between studio sessions for an as-yet-unannounced project.

Selim Bulut: When you started writing Again, was there an initial spark that set you off?

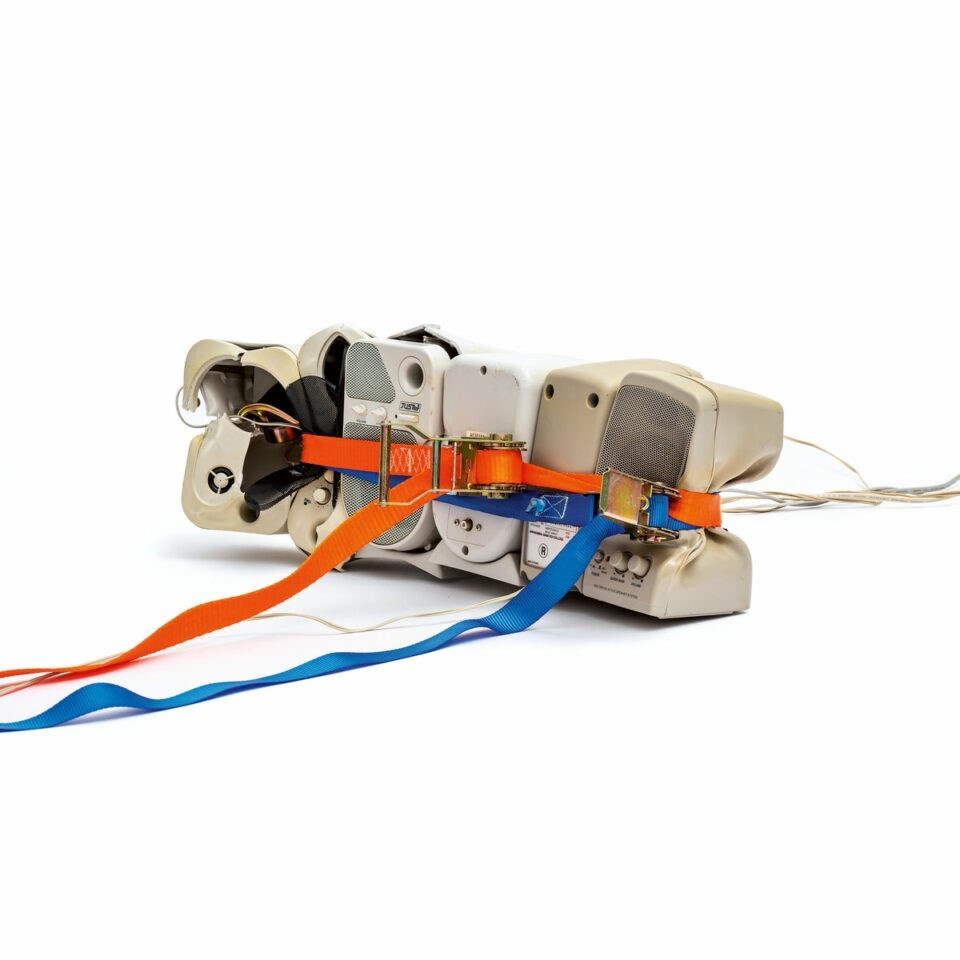

Oneohtrix Point Never: I was going around a lot to second-hand stores upstate and in New England, and I saw these computer speakers. They reminded me of this Matias Faldbakken sculpture. I went back and found a picture of me, having finally seen Matias’s sculpture in the flesh, where I was so proud that I posted it on my Instagram. I was like ‘Man, what is it about this sculpture?’ I then started writing a lot of thoughts on how I arrived at where I am creatively and musically today. Very quickly it started picking up steam. I never had computer speakers; I used my headphones. I realised I was libidinously drawn to the computer speakers because they represented the promise that music afforded me at one point. You squeeze something because you love it so much that it breaks.

I was like, ‘OK, Let’s start thinking about that in terms of what the music sounds like.’ Having Matias involved with this record [Faldbakken created an original sculpture for the album artwork] felt very complete.

SB: Again is described as a “speculative autobiography” that stemmed from this theoretical collaboration between your current and young adult self. When you say ‘young adult’, what age do you mean?

OPN: Young adulthood, to me, is your early 20s. The world hasn’t really gratified you in any way, you’re completely at the whim of the outside world – but you can no longer hide from it. It’s very different to the sublimation of a teenager. Teenagers are just kind of overwhelmed, but if they’re lucky there’s some level of protection or safety that they still have; they’re still children. But when you’re a young adult, you’re finally facing off with very serious questions. What are your values? How are you gonna spend your time? What is it that you’re trying to do here? That’s a very different modality.

“My early twenties were an unbelievably exciting and really beautiful time. I was surrounded by really interesting people for the first time; I’d left my bumfuck town. There was really a bounty of things that were influencing me” – Daniel Lopatin

SB: What were your ambitions at that age?

OPN: I was realising that I was never gonna be cut out for the rat race, but I couldn’t afford not to be, so I had to pretend that this shit was gonna somehow work out. I remember feeling a lot of anxiety and stress around the fact I had this obligation to my parents, who had basically sacrificed their entire existence for my sister and I. That it was my duty to craft some kind of life for myself that would satisfy them. I was putting a lot of unnecessary pressure on myself, while at the same time having an absolutely incredible flowering, musically, and also meeting the best friends of my life, the ones I cherish to this day.

SB: There’s a thing in young adulthood where you sort of understand your parents a bit more, maybe because you’re approaching the age they might have been when you were born.

OPN: I’ve known a lot of people whose parents were their friends. I didn’t have this kind of experience. It’s a cultural thing [Lopatin’s parents immigrated to the USA from Russia]. My parents were always these monolithic rulers, you know? I had to break free of that. That’s the only way you can actually get on with becoming a human being, you kind of have to say ‘no’. There was a lot of wrestling with that.

There was also a burgeoning obsession with music, which I didn’t necessarily have as a teenager. Even though I was in bands and doing music all the time, my obsession was film until my early twenties. It was an unbelievably exciting and really beautiful time. The peer-to-peer explosion was happening. I was surrounded by really interesting people for the first time; I’d left my bumfuck town. There was really a bounty of things that were influencing me.

SB: As a young adult, what sort of alternative paths presented themselves to you that you could have taken under different circumstances?

OPN: My mum was a music teacher. I studied piano with her. If I hadn’t been such a derelict, I can see some bizarre version of me going more in the direction that she inhabits. Instead of playing little Mozart minuets, I would have worked my way up to Chopin and played The Nocturnes or something, but I never did. I got a shitty Fender acoustic guitar for my sixteenth birthday that I brought with me to college and hung on to for years.

My first college band was obsessed with Broadcast and The Kinks and The Who and power-pop. My second college band had a Joy Division/New Order thing going on. I was completely obsessed with jazz fusion. I learned about all the quote-unquote ‘pretentious’ electronic music that was happening in the early 2000s in Europe, and I ended up on one of those labels, Editions Mego. I was exposed to an unbelievable swath of incredibly progressive electronic music and electro-acoustic music on labels like Mille Plateaux and Raster-Noton. There were all these various in-roads that I was exploring, but not taking completely. I was never a person that was gonna settle for one kind of colour; it’s just not my personality. Those are interesting details about myself that I wanted to explore. Why did it end up this way? I try to tease that out on the record, on some level.

SB: They’re not the biggest part of the album, but I thought it was interesting that you used some AI tools on Again. Your 2018 album Age Of was based around the idea of artificial intelligence, so how does it feel now that AI is no longer in the realm of fiction, but real in this almost banal way?

OPN: That’s exactly right, it’s so banal. To me the thing that’s exciting about AI is that they seem to behave a lot like we do, in that they confidently misrepresent ideas, they misconstrue history. Those two things are so on point to me that I was like, ‘Yes, this absolutely belongs in the OPN toolbox.’

SB: I’ve seen people share clips of AI-generated music laughing at how wrong its interpretation of certain genres can be. But to me that’s more interesting to me than a perfect replica.

OPN: This is like the mediaeval period. It’s really funny to me. It can be quite haunting too. I don’t even know where the eeriness ends and the humour begins. I’m not so impressed with it sonically, but using this stuff influenced the arrangements, particularly Jukebox. That’s the one that seems to do the weirdest stuff with rhythm and time. It fails so majestically that we have to take note of it.

SB: AI aside, there are very human collaborators on this record too, like Xiu Xiu, Lee Ranaldo, and Jim O’Rourke. When did you bring them into the process?

OPN: I felt like the record needed the earthiness of the collaborators that I brought in. They’re all so distinct from one another. I can’t think of more emotionally agonised music than Xiu Xiu; I just can’t. Lee represents to me something that’s really present on the record, which is this connection between rock and minimalism. The story of rock that Lee is involved in is the story of ‘academic’ or ‘pretentious’ music becoming populist music. The way that Sonic Youth challenged noise music to be more comprehensible, and also challenged highbrow music to be more punk, is a contribution I can’t even qualify. To have him involved in this record that felt like a microcosm of the things I was realising as a young musician was a huge privilege. And Jim too – if you hear Jim talk about how he came into his own musically, it was exactly this kind of thing, it was tape cassette culture and the collapsing of high and low as home recording became more accessible. I also just appreciate them as musicians. It was a no-brainer.

Again by Oneohtrix Point Never is out now.