Following the news of Dariush Mehrjui’s death, we look back at four of his greatest films, which interrogated the psychological and social ramifications of existing under an oppressive political system

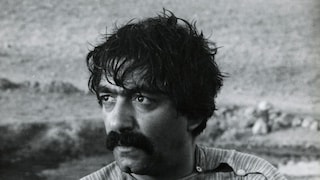

On the October 14, the news that the filmmaker Dariush Mehrjui and his wife, the screenwriter Vahideh Mohammadifar, were murdered at their home in Tehran flooded social media, sending shockwaves across the industry. A fixture of global cinema and vocal critic of state censorship, Mehrjui dedicated his career to creating a filmography of visually striking and emotionally dense works. As one of the pioneering figures of the Iranian New Wave, which preceded the 1979 Islamic revolution and was characterised by experimental visual choices and a poetic disposition, Mejrjui’s films laid the groundwork for contemporary Iranian cinema.

Anecdotes of Mehrjui’s childhood in Tehran, recounted by the American film critic Godfrey Cheshire, describe how the filmmaker would build his own 35mm projector, rent film prints and hold screenings in his neighbourhood, revealing the filmmaker’s nascent attachment to the medium. Later, he pursued film studies at UCLA but was discouraged by the rigidity of the curriculum – which favoured Western cinema – and moved his focus to philosophy and literature instead. While his love for cinema rekindled as he returned to Iran, Mehrjui’s academic background foregrounded the stories he lensed. The filmmaker frequently drew inspiration from literary sources, exemplified by works like Postchi (The Postman) in 1972, which was based on Georg Büchner’s Woyzeck and a close adaptation of JD Salinger’s Franny and Zooey, titled Pari (1995).

The themes in Mehrjui’s cinematic oeuvre, albeit veiled in allegory, critique the political ideologies that dictate Iranian life. In the early years of his career, the filmmaker was concerned with capturing the plight of Iran’s most disadvantaged classes under Pahlvi’s monarchy, but following the 1979 revolution, Mehrjui’s stories began interrogating the psychological and social ramifications of existing under an oppressive political system. In films such as Banoo (1992) and Leila (1995), this sensibility is extended towards the interior lives of Iranian women caught between opposing spheres of tradition and modernity. To Mehrjui, films were intimately tied to matters of class, creed and gender and, by extension, his affecting narratives were seen as controversial and were banned by both the Shah’s regime and the Islamic Republic.

In light of his recent passing, we honour the life and legacy of Dariush Mehrjui by revisiting four of his most influential films.

Gav / The Cow, 1969

Based on a story by Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi, Mehrjui’s neorealist drama The Cow, which follows a poor farmer’s all-consuming love for the titular character, is often considered to be the film that kicked off the Iranian New Wave by virtue of its experimental format and philosophical narrative. Through a Kafkaesque storyline, the filmmaker is attentive to Marxist theories of social alienation, portrayed through a man’s attachment to his cow and the grief that ensues when it mysteriously dies. Although it received funding from the Ministry of Culture and Arts, Mehrjui’s representation of rural impoverishment during the Pahlavi regime contradicted the image of modernity that the government wanted to portray, and thus faced the wrath of censors. The film was subsequently smuggled into film festivals, such as the Venice Film Festival, where it won the FIPRESCI Prize, and has since cultivated a cult following.

Dayereh-ye Mina / The Cycle, 1974

The unsettling narrative of Mehrjui’s The Cycle, which uncovers with staggering clarity the realities of poverty, drug abuse and blood trafficking within urban slums in Iran, is yet another adaptation of Saedi’s leftist literary work, namely The Garbage Dump. The film revolves around Ali, portrayed by Saeed Kangarani, who gets entangled in Tehran’s illegal blood trade in his attempts to afford medical treatment for his ailing father. Due to its pointed exposition of Iran’s medical industry, The Cycle was shelved for three years until it eventually premiered in 1977, partly due to pressure from Jimmy Carter’s administration to promote intellectual freedom in the country. Its influence and international success has been cited as a contributing factor to establishing the Iranian Blood Transfusion Organisation.

Ejareh-Nesheenha / The Tenants, 1987

Written and directed by Mehrjui in the post-revolutionary period, The Tenants is a witty satire that unravels the conflicts among the tenants of a building in the aftermath of their absentee landlord’s death. Considered one of the country’s most influential madcap comedies, which went on to inspire multiple television series, the film cemented the director’s presence within Iranian cinema. While the film’s peculiar cast of characters and the exaggerated dialogue lends to its commerciality, what sets the film apart is its covert display of bourgeois life in Iran in the 1980s.

Leila, 1995

In the 1990s, Mehrjui released a trilogy of films that attempted to paint a portrait of life in Iran for the modern woman. Titled Sara (1993), Pari (1995) and Leila (1996), these films are punctuated by oscillating themes of spirituality, materialism, cosmopolitism and Orthodox Islamic tradition. Leila, referenced by critic Amy Taubin in The Village Voice as “the most brilliant depiction of a marriage gone to hell”, stands out in terms of its aesthetic and social complexity. The protagonist, played by Leila Hatami, is stuck between her love for her husband, Reza and the ramifications of her infertility. Amidst the backdrop of Islamic polygamy and conventional notions of familial heritage, Mehrjui’s film adeptly explores the intricate gender dynamics that irrevocably alter the life and love of the young couple.