Directed by Lois Patiño, Samsara starts with teenage monks in Laos and ends with seaweed farmers in Zanzibar. “You open your eyes to the different ways of living,” he says

The middle section of Samsara is like nothing you’ve ever seen before, and, by the time it finishes, you still haven’t seen it. Directed by Lois Patiño, the docufiction feature starts with teenage monks in Laos and ends with seaweed farmers in Zanzibar. Halfway through the film, though, an onscreen text asks viewers to shut their eyes for 15 minutes, during which a soul is transported across the globe. “Somehow, we float, but maybe in a more literal way,” says Patiño. “You close your eyes and disappear from the real world.”

When cinemagoers shut their eyes, flashing lights appear on the screen so powerfully that they seep past closed eyelids and rattle around one’s headspace. At the same time, an evocative soundscape alludes to a spirit passing through various continents and habitats, all of which conjures up wild imagery in the brain. Basically, Samsara is a transcendent, theatrical experience, like a metaphysical twist on 4DX – at least, if you obey the instructions that pop up in the film.

“Most people close their eyes,” Patiño tells me at Curzon’s offices during the London Film Festival, the morning after Samsara screened at BFI IMAX. “Some of them are curious about what’s going on, so they open their eyes a little bit. I tried to make the image not too beautiful, because I didn’t want to tempt them. But I couldn’t resist making it a little bit beautiful.” And if we want to know afterwards what we missed? “People that experienced the film as I suggested with their eyes closed, they can see what I used for lights in the credits.”

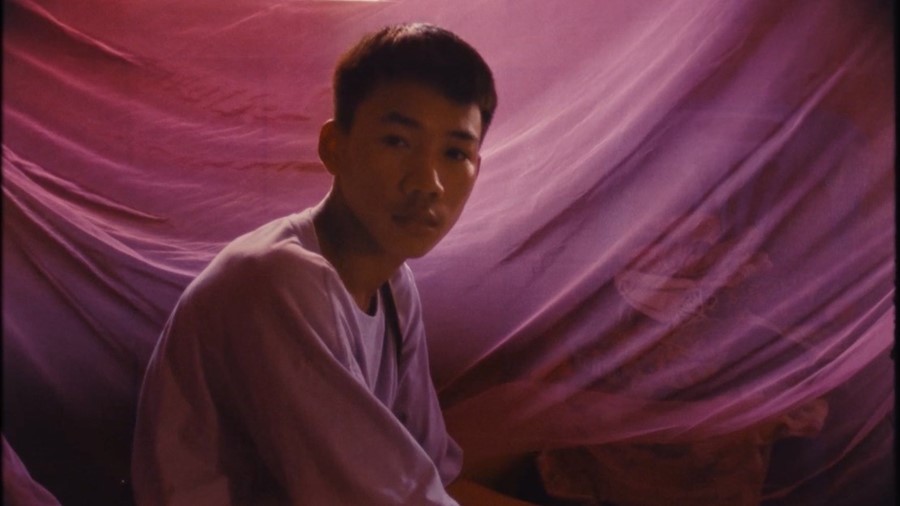

Co-written by Garbiñe Ortega and Patiño, Samsara is technically a three-act movie, albeit not one following a traditional plot structure. In the opening stretch, the film appears to be a documentary about a Buddhist temple in Luang Prabang that pays extra attention to male monks at the precipice of adulthood. For two months, Patiño lived in the temple and studied their daily, repetitive routines. “I chose some monks who are 17,” says the 40-year-old Spanish director. “When they turn 18, they choose if they want be a monk or do something else. Most of them aren’t monks anymore. The main actor is studying at university.”

The fictional element is that a young man, Amid, crosses the Mekong River every morning to visit an old, sickly woman and read aloud passages from Bardo Thodol – also known as The Tibetan Book of the Dead – about how life is cyclical. “As the film is about reincarnation, I needed somebody to die,” says Patiño. “This description of the afterlife is the trip we’re going to do with our eyes closed.” After the aforementioned 15-minute journey from one life to another, the action switches to Zanzibar where a goat is born. “I thought about reincarnating into a goat, because I wanted to bring a new perspective – not only in terms of culture and religion, but also human and not human. We look at reality from the perspective of a little goat.”

While the Laos section is lensed by Mauro Herce, the Zanzibar sequences have Jessica Sarah Rinland as the cinematographer. The contrast between the male and female gaze is deliberate, Patiño explains, as is the focus on female seaweed farmers after spending so much time with male monks. “I wanted a high contrast with Laos, so we went to a Muslim island in Africa. I got immersed in that community of women: speaking to them, listening to them, understanding their way of living. The women were their own bosses, working in an open place, on the beach, in the water, singing.”

With three features and several shorts to his name, Patiño has long been experimenting with the hypnotic powers of cinema. For instance, Night Without Distance, a 21-minute film, was shot entirely with infra-red cameras, while his Vimeo page includes “sound work” inspired by submarines. Samsara, though, has proven to be a breakthrough, not just because it won a top prize at the Berlinale, but the word-of-mouth effect is undeniable: let’s face it, you know it as the film where you shut your eyes for 15 minutes.

In Alejandro Iñárritu’s Bardo, a shadow briefly hovers over a desert; in Gaspar Noé’s Enter the Void, which also namechecks The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the camera repeatedly floats from a spirit’s perspective. For Samsara, Patiño knew he was creating something new, and the middle section was repeatedly tested at home on his laptop. “It was difficult,” he recalls. “I’d experience the flashing myself, but when I had my eyes closed, I didn’t know what was happening on the screen. I had to do a lot of trials. When I went to the cinema and didn’t like the film, I’d close my eyes to experience what it was like in a theatre.”

Since the shoot, Samsara has screened for the actors in Zanzibar (“they were crying a lot”) but the monks, many of whom use smartphones in the film, were sent online links. I question whether it’s safe to shut your eyes while watching a movie on your phone. “I told them to be in a dark place. With a computer, it still works. There are meditation apps that you experience with lights on your phone – I’ve tried it.”

Throughout the interview, Patiño stresses how much research went into Samsara and its various cultures: two months living in Laos, another two in Zanzibar. He admits that as a white European visiting these countries, there was a risk of cultural appropriation. “We triple-checked the dialogue with the local crew and actors,” he says. “For me, it was about listening and observing. The film celebrates the culture of diversity, and is an exercise in learning from others. It’s not about teenagers in Laos, and neither is it about women working on the Zanzibar seafront. It’s something else. 90 per cent of screens around the world show Western culture. It’s important to show different cultures.” So, actually, you have to open your eyes, not close them? “Yes. You open your eyes to the different ways of living.”

Samsara is out in UK cinemas and is streaming on Curzon Home Cinema now.