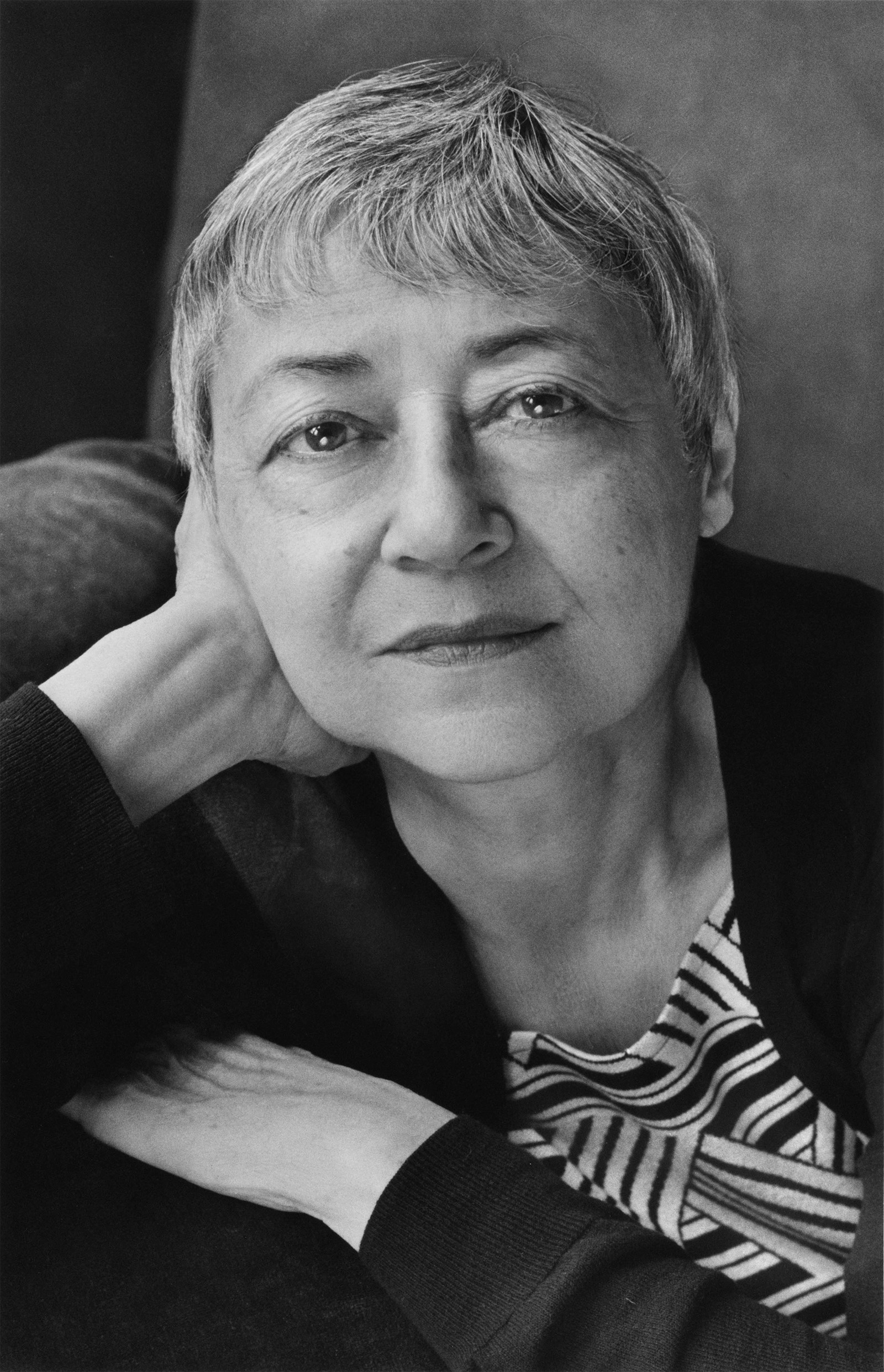

“Something is missing. Something has been lost. I believe this is at the heart of why I write.” In the opening pages of Sigrid Nunez’s new novel, The Vulnerables, the protagonist – an older New York writer who sounds suspiciously close to the author herself – reflects on the purpose of her work. At the same time, the city around her is being slowly evacuated. It’s the early days of 2020’s Covid lockdown, a period defined by a pervasive sense of loss, and the unnamed narrator is spending much of her time wandering the streets alone. Along with confronting the many “uncertainties” of that time – namely her status as a “vulnerable” person – there’s a deeper issue rising to the surface: “I want to know why I feel as though I have been mourning all my life.”

In 2024, writing about the pandemic, or even just talking about it, will induce a few eye rolls. We’ve all moved on, it was horrible, what more is there to say? The idea of ‘a pandemic novel’ is even worse. But this willingness to look away, to forget, is not compatible with Nunez, whose artistry shines in her quiet, soulful contemplations. Her books, especially in recent years, have centred on the complex ways we heal from loss, as well as the fragile but precious nature of human connection. “I thought of it more as a lockdown novel than a pandemic novel,” she tells AnOther. “I also felt like, for the first time in my life, I was writing about something that everyone on the planet also knew and was experiencing.” There’s also a lot to be gleaned in her books about how to live more mindfully and imaginatively, with Nunez often weaving in the wisdom of writers like Proust, Joan Didion, Oscar Wilde and Annie Ernaux.

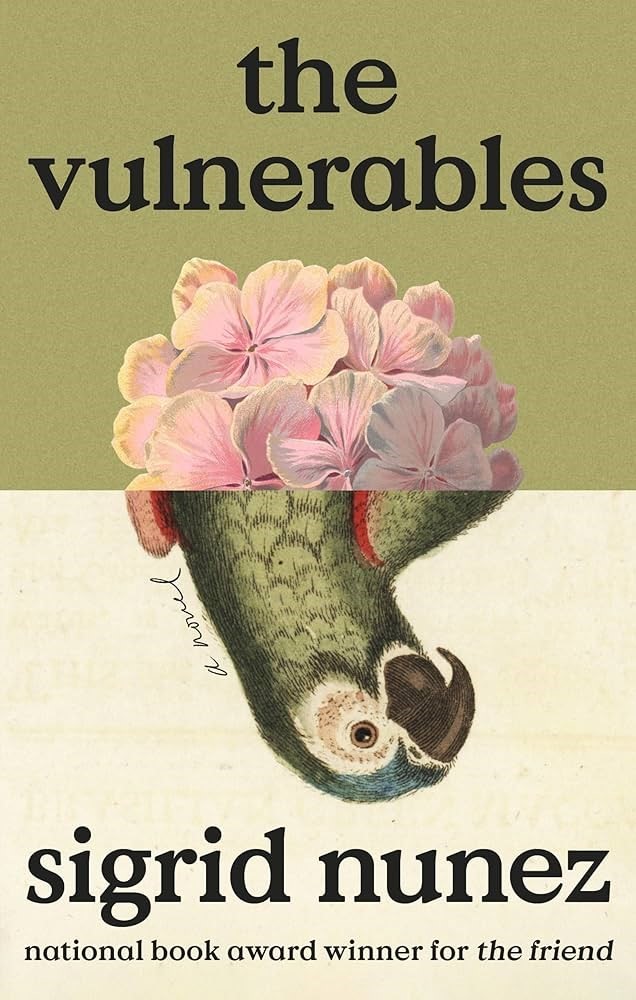

The Vulnerables is the 73-year-old’s ninth novel, following on from 2018’s National Book Award-winning The Friend and 2020’s What Are You Going Through. It follows the story of the solitary narrator as she finds herself locked down with a friend’s parrot (animals are another recurring theme in Nunez’s work) and a handsome young NYU student (a man “born to privilege, raised in privilege, and forever railing against privilege”). As the pandemic wreaks havoc on the world around her, the narrator is forced to face the parts of herself – her prejudice, fragility and motivations – that she had previously overlooked.

Here, Sigrid Nunez tells us more about the themes that inspired the book.

Dominique Sisley: Why did you want to return to the pandemic? Did you have any hesitations about writing a ‘pandemic novel’?

Sigrid Nunez: I already did write a pandemic novel that came out in 2010 called Salvation City, in which I imagined a flu pandemic. Then 2020 came along. We’d been in lockdown for a month, and I was having an annual faculty reading at Boston University, where I teach. I had not been able to write at the beginning of the lockdown – like a lot of people, it was hard to get any work done. So I decided to write about what was happening. I started with the phrase, ‘It was an uncertain spring,’ which came from Virginia Woolf’s The Years. It came to my head for all the obvious reasons. So I put it down and I wrote a few pages. One idea then led to another.

DS: Is that your approach when writing novels? You just start, with no plan, and see where it naturally goes?

SN: Yeah. For a lot of writers, that would be out of the question; they want to have an outline and know what’s going to happen. But for me, it’s completely different. Just as I said, that sentence [from Virginia Woolf] came into my head and then I just went with it. I like to move as ideas keep coming to me, and then when I get a certain amount of pages, maybe ten to 15, I keep revising those pages as much as I can until they’re as good as I think I can make them. Then I move on to the next ten or 15 pages. By the time I get to the end of the book, it’s finished. I don’t have to go back, because it’s not a rough draft. It’s a final draft that has been gone over and over again, while I’m writing it.

“Even if you are quite young, so much of life is about loss, because that is the nature of time. It takes everything away, without being melodramatic” – Sigrid Nunez

DS: In the opening pages, you write that you ‘feel like you have been mourning all your life’. How common do you think that feeling is? Is a sense of yearning or longing an unavoidable part of a person’s life?

SN: Well, I think the trauma of the pandemic and lockdown accentuated that sense of mourning or loss for all kinds of people. But I do think it is at the heart of why I write. And I don’t think it’s me, I think it’s everyone. Even if you are quite young – and I am not quite young – so much of life is about loss, because that is the nature of time. It takes everything away, without being melodramatic. When you’re young, you move from one school grade to the next, you make new friends but lose some of your old friends, your grandparents die, you move to a different neighbourhood. You get older, and people lose their youth, their looks, their partners and friends and so on ... it’s just so much a part of human life. And you share that with everyone else, which I suppose is largely what makes it bearable. But by the time you are a certain age, so much of your life, so much of what you had, isn’t there anymore. But you will get nostalgic about it: you will remember that time and all the excitement that came with it. It’s the way of the world, feeling that you’re mourning all the time, because every day you’re saying goodbye to something.

DS: There was some talk of ‘anticipatory grief’ in the pandemic; this idea of mourning the future as well as the past. Do you think that’s possible?

SN: Yeah. For young people, it was particularly acute because they were missing out on that year of college, [the youth] that they were not going to get back. They missed their graduation. They missed their senior prom: these were not were not going to be repeated. So yeah, I think the lockdown made that sense of mourning even more acute.

Also, along with all that, there is a certain amount of confusion in the place of resolution. A culture goes through a war and the war ends, and life goes on. But the pandemic didn’t have that [resolution]. People‘s lives were all up-ended and then they did their best to carry on. They’re doing such a good job of it, that now we’ve stopped remembering or paying attention. What effect that will have, we don’t know yet. There might be a price to pay for that in future.

DS: A lot of this book is about getting older. How have you found that experience? How has it changed your relationship with yourself and your work?

SN: People think that ageing isn’t interesting. It’s not something that, when you’re young, you think about with fascination or interest. Why should you be thinking about ageing, right? You shouldn’t be, in my view. But then when you reach a certain age, you discover that it’s anything but boring. It’s sort of endlessly interesting, at least to the person who’s going through it. I think that for a writer, or at least my kind of writer, it tends to make you more reflective. It makes you look harder at life, to try to understand it better, to make a narrative out of it. And then you become acutely aware of the shortness of time – like what do you want to do with your life now? You don’t have 50 years ahead of you.

“The pressure of an early success, I’ve seen that go very wrong in some very talented people” – Sigrid Nunez

DS: You got the recognition that you deserved quite late in life, finding major commercial success in 2018. You’ve said before that your twenties were quite tough for that reason. Did you have any struggles with self-doubt?

SN: I think I always had some self-doubt. My first book wasn’t published until I was 42, and my first important story in a respected literary magazine came out in 1988. The whole time, through college, out of college, and through graduate school, I was writing and sending out stories. I did publish one or two things, and I got some awards, fellowships, and a certain amount of encouragement. But it did seem to be harder for me than it was for a lot of other people. But I was always doing what I really wanted to do. I was writing – I wasn’t succeeding, but I always knew that this was what I wanted to do. I was really not good for anything else. I can’t imagine what else I would have done. So that was it.

The biggest difference came with the National Book Award; that was the big change. But really, I think it just comes down to the fact that I wasn’t distracted by the things that distract other people. I didn’t have another profession. I didn’t get married, I didn’t have children. I have always lived close to the bone: I didn’t mind living in one room and not having money or a certain kind of security. The biggest difficulty for me was coming up with paying for health insurance – that was extremely difficult and got harder every year. But I didn’t want other things so badly that I couldn’t devote myself to this, and feel like I was doing what I should be doing.

DS: How do you feel about this kind of commercial success now that you have it?

SN: Very lucky. There’s a really good side to this having come so late. First of all, it’s not in the past. I can enjoy it now. If it happened a long time ago, who knows where I might be now? I might be unpublished. People don’t stay successful forever, necessarily. I feel like if this had happened with my first book, or when I was very young, my whole life could have been different – in a good way, but also in a bad way. The pressure of an early success, I’ve seen that go very wrong in some very talented people. I already knew what I wanted to write, and who I was as a writer, so there was no pressure, no expectation. I had a certain freedom. And I think that when you have a lot of success early on, you don’t necessarily have that freedom, and I think it can be very confusing. There’s a lot to be said for this having happened later in life.

The Vulnerables by Sigrid Nunez is published by Virago, and is out now.