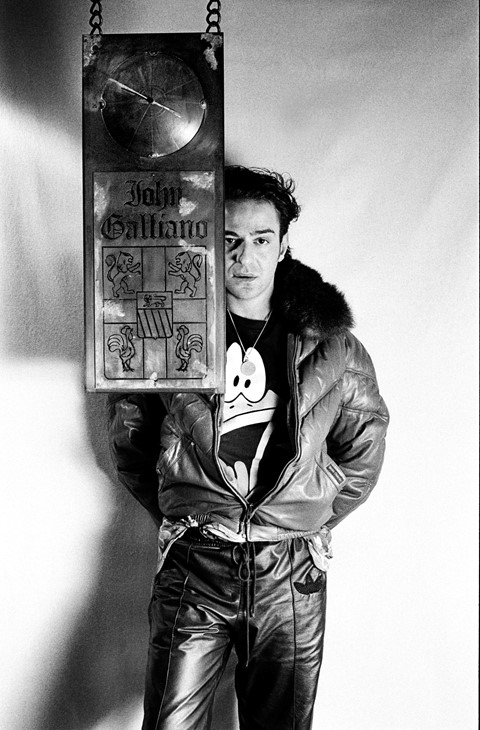

Director Kevin Macdonald opens up on his new documentary High & Low, a riveting account of the fashion visionary’s complex “fourth act”

Within the informal justice systems of social media, anyone has the power to play judge; its flattening format reduces debate to black-and-white and there is seemingly little space for redemption. It’s this question of what forgiveness could look like in the internet era which drives director Kevin Macdonald’s thrilling new documentary, High & Low. By following designer John Galliano’s spectacular fall from grace after his repeated hurling of racist and antisemitic remarks in a Parisian bar, Macdonald asks, “What happens next to all these people? How does society cope with it?’”

This is not Macdonald’s first biopic: his 2018 documentary Whitney followed the rise and fall of R&B powerhouse Whitney Houston. But unlike Whitney, and sadly many other tales of addiction, Galliano’s story has what the director calls a “fourth act” – his and society’s reckoning with what he did. “You have this last act which is all these people – his therapist, his addiction counsellor, his lawyer and others who are part of the story at that stage – talking about the consequences for them, for John, and the fashion industry,” says Macdonald. “The film became philosophical, which is not what I expected.”

High & Low unfurls in the grey muddle of human complexity. The film never reaches resolve or judgment; Macdonald simply lays out the facts through extensive archival footage, interviews with Galliano, and with others involved in the story. “People want to feel that either my film is made to excuse him or that it is damning of him,” he says. “And it’s neither to me. I’m presenting my experience of being with him, talking to him, examining his career.” The only conclusion Macdonald came to was that, even after spending a year and a half making the film, he could only ever have a nuanced understanding of Galliano: “I think the nub of it is: does he believe he’s done something hurtful and horrible and racist? Yes, you can see that and see that he did. Do we know how deeply he felt those things? Whether he really felt antisemitic? Or [if it was] self-destruction? We will never know.”

Similarly, Galliano never tried to contort the opportunity to tell his story as way to beg for mercy. “He never objected to anything in the final cut,” recalls Macdonald. “He said, ‘This is yours. You’re the filmmaker. You know best. I wouldn’t want you interfering in my atelier.’” If there are times when the designer’s eloquence can feel rehearsed, Macdonald is quick to point out that Galliano never worked with a PR and that it’s hard to hide behind prepared answers when you’re being interviewed for 30 hours. One only has to watch a Galliano fashion show, which are almost always fantastical narratives of escape, to comprehend the designer’s inherent theatrical temperament. “The day before the interview, I went to see him and he asked, ‘Oh, what should I wear? How should we do my make-up?’” Macdonald laughs. “And I said, ‘I just want you to be yourself.’ I could sense he was like, ‘Oh… how do I play the role of being myself?’”

The real-time narrative is spliced with footage from Abel Gance’s Napoléon (1927), and Emeric Pressburger (Macdonald’s grandfather) and Michael Powell’s The Red Shoes (1949). Each has parallels with Galliano’s story: he was an outsider who conquered Paris and he pushed himself to the limits of sanity through dedication to his craft. But the cinematic references were also a way to bring “a bit of John’s sense of panache and fantasy into the film”. “The first time I saw [Galliano] in the south of France, we started talking about the influence of [the film Napoléon] on him,” recalls Macdonald. “There’s a very famous scene where Napoleon stands on the rocks and looks at sea. I asked John to just step on the rocks and pretend he was Napoleon, and I began to see more and more of these parallels.”

So how can someone like Galliano be forgiven today? One of the first people Macdonald spoke to was Rabbi Barry Marcus, who worked with the designer to educate him on the Jewish faith and history, and to help repair his relationship with the Jewish community: “I wish [Rabbi Marcus] had said this on camera, but he said to me, ‘What’s the point of religion if we don’t believe that people can change?’” But in the absence of the redemptive mechanisms offered by religion, High & Low raises an important human lesson: to be able to hold two truths in one sentence. Yes, Galliano did something terribly hurtful and yes, he is a genius designer. “We’re in danger of making the world really boring and unforgiving because we are not allowing for errors, sin or nuance,” says Macdonald. “We need to allow for a mature enough view of humanity that we believe people can still be worthy of our love and our attention.”

High & Low – John Galliano is out in cinemas from March 8.