As Ethan Coen and Tricia Cooke’s Drive-Away Dolls is released in cinemas, we look back at five trailblazing queer road movies that paved the way

The allure of the open road has long tempted filmmakers, from the vast, silent sandy plains of Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas to the screeching tyres of three blood-lusty dancers in Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! Kill!, one of the inspirations behind Drive-Away Dolls.

Ethan Coen and Tricia Cooke’s riotous road adventure is the latest entry into the queer road movie canon. Unapologetically pulpy, uninhibited and even joyful, the film ushers the queer road movie into a kaleidoscopically coloured new era.

More widely, the road movie genre allows characters fed up with the tedium of daily life to unshackle themselves from the clutches of convention, driving in pursuit of a more utopic way of living. Some protagonists even go down in history as law-rejecting legends, from working-class lovers in crime Bonnie and Clyde to Queen and Slim, hailed as symbols of the fight against systemic racism.

With the lens trained on those pushed to the edges of society, the road movie contains all the perfect ingredients to explore queerness. Rife with vagrants and vagabonds, the subgenre is a close partner of the queer crime movie, where characters rip up the rulebook and exact their own forms of personal justice. Thelma and Louise, for example, one of the most queer-coded films in movie history, follows the eponymous pair as they ditch their humdrum lives for a holiday but run into trouble, getting their own back against the men who’ve mistreated them.

In the wake of the gay liberation movement, the rebellious queer road movie exploded into cinema in the early 90s. “My theory of road movies,” director Gregg Araki said in a recent interview with Metrograph, “is that they tend to come out in times of social and economic crisis.” Recently, we’ve seen a resurgence through the likes of The Man With the Answers, a gentle road romcom taking in the sights of Italy and Bavaria, Runs in the Family, a South African film where a father forges a connection with his trans son and, fresh from Sundance, Julia de Castro and María Gisèle Royo’s On the Go, a euphoric queer, feminist escapade in which a mermaid is the drivers’ guiding light.

Below, we explore five essential films that blazed a trail for the queer road movie today.

My Own Private Idaho (1991 – lead image)

One of River Phoenix’s final roles before his death in 1993, this Gus van Sant drama – loosely based on a John Rechy novel about two male sex workers – opens on Mike (Phoenix) pacing the side of the highway in the middle of nowhere, feeling strangely as if he has been here before. Co-star Keanu Reeves had to personally deliver Van Sant’s script to Phoenix, whose agent had refused to let him read it, such was the stigma around Hollywood actors taking on gay roles at the time. Good job he did: Phoenix is electric in this wounding, wistful reverie on youth, aimlessness and unrequited love.

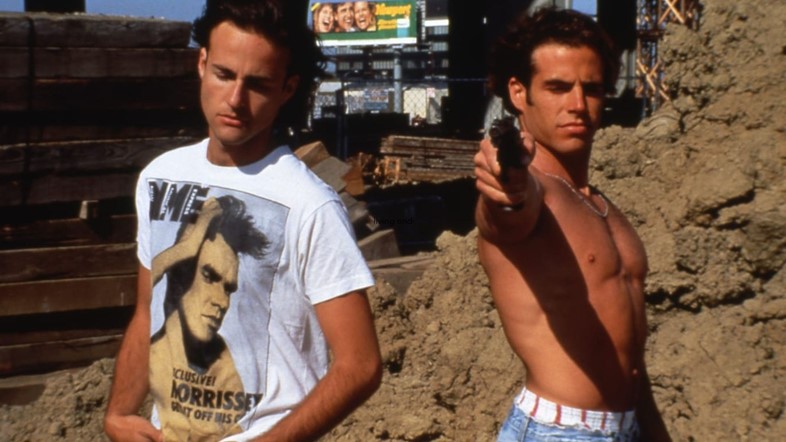

The Living End (1992)

A close contender with Araki’s other film on four wheels, The Doom Generation, this semi-apocalyptic romance is not only among the most iconic queer road movies, it’s one of the biggest landmark LGBTQ+ films full stop. Araki’s “irresponsible film” follows Luke, an angsty, devastatingly attractive nomad, and Jon, a sweet-hearted but tetchy film critic. After Luke kills a cop, the duo – both HIV positive and in doubt about their future – throw caution to the wind and embark on a swoon-worthy excursion across the US. Littered with graffiti, heavy metal and a series of unsettlingly strange, ephemeral interactions between minor characters, Araki’s early entry into the queer new wave canon is a cinematic blast of rage railing against the injustices of society.

Read AnOther’s guide to the cinema of Gregg Araki here.

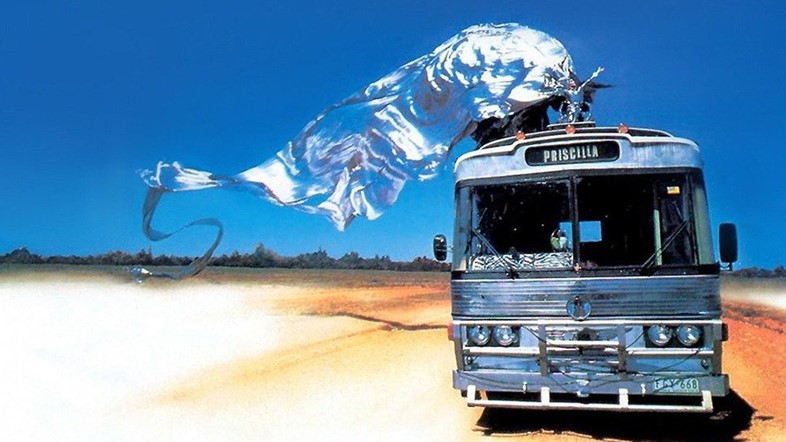

The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994)

A trio of drag queens from Sydney take a shabby but chic tour bus out for a whirl through the Australian outback. Their destination: a hotel casino in rural Alice Springs, where they will serve their flamboyant act to the uninitiated locals, and where Tick, leader of the pack, will reunite with his secret wife and son. Now cemented as an LGBTQ+ cult classic, this film far outstrips its American twin To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar, which also sees three queens wind up stranded in the desert. The only film in which you’re likely to see Guy Pearce in a stunning, billowing coruscation of silver atop a moving vehicle, Stephan Elliott’s film is an earnest ode to the queer chosen family and a glowing, hopeful entreaty for a more accepting future.

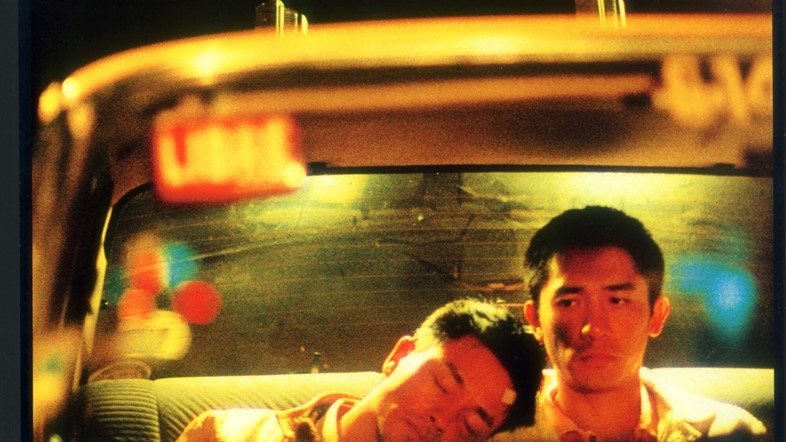

Happy Together (1997)

While you’re probably familiar with Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, it’s well worth seeking out the Hong Kong director’s unjustly lesser-known feature Happy Together. A stop-start, off-again-on-again road movie, the story opens on the side of a motorway in Argentina, as gay couple Ho Po-Wing and Lai Yiu-Fai study a map to work out their way to Iguazú Falls. A slight spoiler: they won’t make it to this spectacular beauty spot together, as their relationship wends in and out of rifts and reconciliations. Shot in shimmering black-and-white and colour with Wong’s trademark crimsons and nicotine yellows, this is a deeply stirring rumination on making peace with unhappy endings.

Read AnOther’s guide to the cinema of Wong Kar-wai here.

The Daughters of Fire (2018)

Queer women and non-binary people have historically been less represented in queer road movies, with hints at relationships between women in road trip films like Boys on the Side, but in the last few years female directors have been redressing the balance. The vibrant Drive-Away Dolls puts the lesbian road movie firmly on the map. But before this, there was Albertina Carri’s story of three women on a quest to rid themselves of the influence of the patriarchy, making a porn movie along the way. Their polyamorous journey is a flaming and fierce retort to the male gaze, attempting to redefine sexuality and sensuality beyond the bounds of a male-dominated society.