How have people’s lives been shaped by the print matter they collect? In a new column for AnOthermag.com titled Paper View, Norwegian publisher, curator and critic Elise By Olsen sifts through the libraries of various cultural figures, learning more about their lives and careers in the process.

At the end of February, I’m on a train traversing the flowery fields to visit the fashion image specialist and curator Adam Murray in his new home in Vivienne Westwood’s birth town. I feel like the birdman of Derbyshire as I step off the train in Glossop, a bowl beneath peaky valleys, carrying Adam’s 2012 photo book Road and Rail Links Between Sheffield and Manchester, the format resembling one of those old pocket-sized travel books. Murray’s practice spans from self-publishing and curating, to teaching Fashion Image at Central Saint Martins for the past seven years. And although I’m not hang-gliding like Steve Coogan’s entrance in the Manchester-set 24 Hour Party People (which I’ve just watched the night before), I am, in fact, here in the Peak District to browse Murray’s collection of printed matter with a bird’s eye view.

Murray moved here with his wife, the painter Evie O’Connor, to her native Glossop nearly one year ago, forcing him to – yet again – go through all the magazines and photo books he has assembled over the last 25 years. Murray has moved with his paper load about 15 times – growing up in a small town near Loughborough in the East Midlands, then to Preston, a small city on the north bank of the River Ribble in Lancashire, where he studied photography at the university, and eventually to Manchester via London and now back up to the North – with his collection being condensed each time. “Every time I moved houses I had to downsize a bit, and tried to get rid of some things,” he says. “This is the first place we have lived where we have enough space to store everything. In London, everything was in boxes, but here you can actually access it all, and see it. As you unbox your books and magazines you see what you need and what you don’t.”

I enter through the front port of his newly redone terraced house, straight into a charming living room with terrazzo flooring – white and bottle green walls with grey powder-coated radiators – and wall-hung aluminium shelving in the room’s nook. There’s a sky-blue kitchen (that is, if the sky is ever clear blue here in Glossop) looking out on the house’s garden plot, and in the background, the long plains of the Pennines, with Snake Pass crossing over to Ladybower Reservoir. This exact route, with a stop in Glossop, is illustrated in Road and Rail Links Between Sheffield and Manchester, as Murray and Theo Simpson, another photographer, travelled between the two cities for three days with trains, buses and cars, documenting transport connections on rails and roads. Little did Murray know then that he would move here 12 years later.

After his time self-publishing and making zines in Preston, Murray had the urge to return to a smaller town in the North. For collectors, there’s an increasing desire for more solitary and remote places. Yes, it could be romanticism or nostalgia, but also a want for their belongings to have more room for less money. “I keep my head down and heart grounded by distancing myself from the big cities,” says Murray. “Digital tools have also allowed for more decentralised lifestyles and practices. With that in mind, how can one work?” From the fringes of fashion, Murray has done multiple projects celebrating creativity outside the big metropoles, among them North: Fashioning Identity, an exhibition he co-curated with Lou Stoppard on the North’s influence on fashion (and its tension with the South). The exhibition contained some books in vitrines, but mostly images and prints, and toured from a specialist photography gallery in Liverpool, via Somerset House, to a space in Yorkshire. Murray’s practice also extends into organisational projects such as the Copeland Book Market, a book fair that he co-organised at a car park in Peckham in 2012.

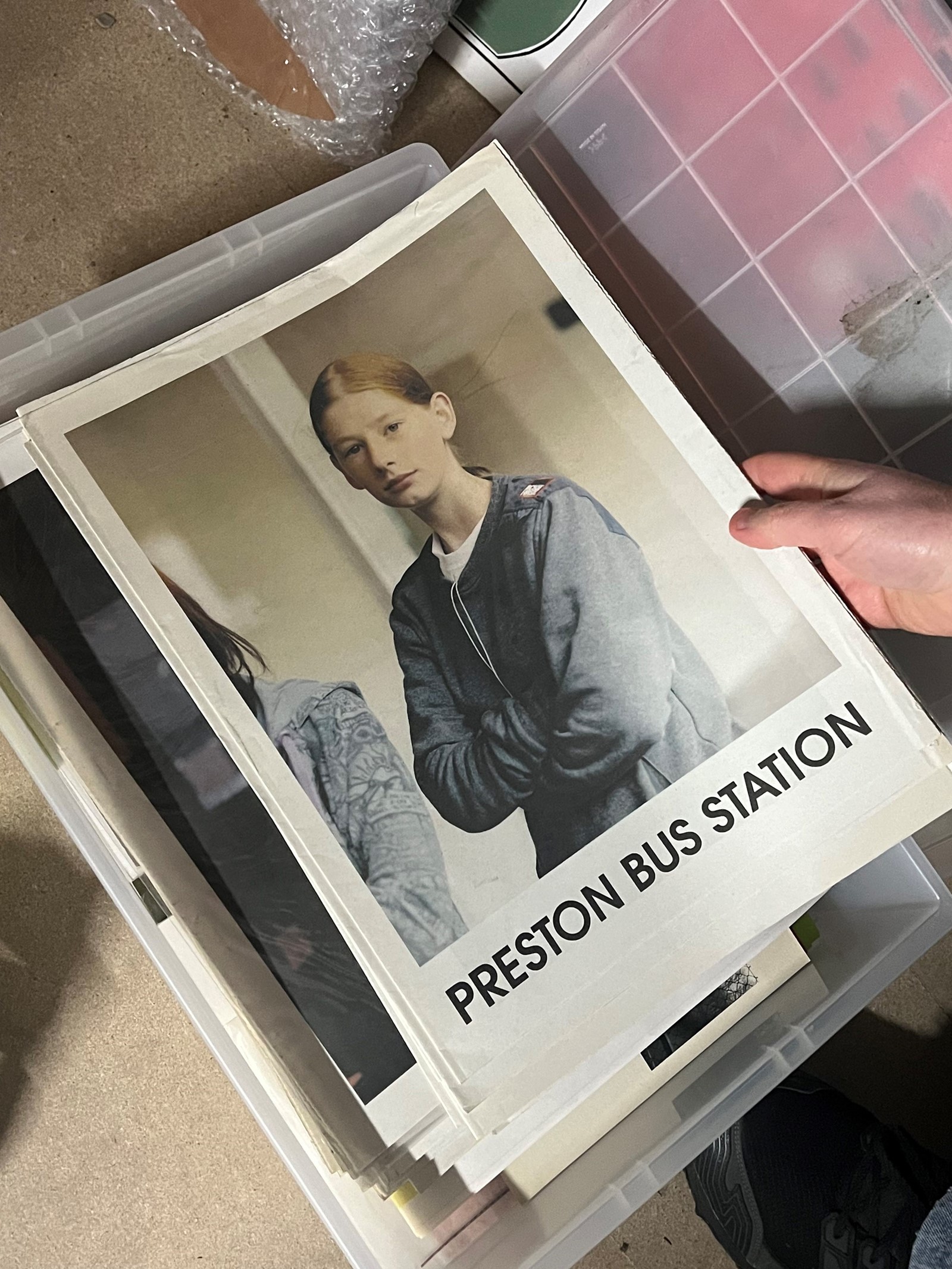

Back in the living room, Murray brings out the original issues of the first publishing project he did. “Preston is my Paris was a project that grew out of a fascination with the North. There was nothing happening in Preston, but my friend Robert [Parkinson] and I were really into it, we had a lot of friends and a great life up there, and we wanted to show how fantastic the place really was,” says Murray, “We did photocopies for free at the university, bought a long arm stapler and did special prints at the chemist, and started making these little zines in editions of 50 or 75 that were given away for free around Preston. Sometimes we used double-sided tape to glue other prints or Polaroids to the cover. It was low quality, black and white Xerox” From 2009 to 2019, the pair did 15 issues, among them special issues on the local bike race “Tour de Preston” (the logo mimicking the original), one featuring photographs of various objects found on the street around Preston, and one featuring photos of old DVD rentals and shops that no longer existed, thus becoming capsules of a specific moment in time.

“I keep my head down and heart grounded by distancing myself from the big cities. Digital tools have also allowed for more decentralised lifestyles and practices” – Adam Murray

Another Preston is my Paris project was created in collaboration with Murray’s former student, the fashion and documentary photographer Jamie Hawkesworth, about “Preston’s most important architectural landmark” – a brutalist bus station. “We set up a project space in a disused shop in the bus station and produced a photographic document – a newspaper – of the building and the people that use it,” he says. Murray’s photo book collection is mostly downstairs in his living room, and Hawkesworth is otherwise widely represented, in addition to the likes of Nigel Shafran, Deana Lawson and Lars Tunbjörk– books on books and magazine making, such as Vince Aletti’s Issues – and zines by collaborators and peers. “Community is such an important part of my life in collecting,” says Murray. “I’ve developed many friendships through publishing and it is interesting to see what people who I first met through early book fairs or events are now doing.”

I ask Murray what role his collecting plays in his teaching. “My knowledge of this culture has pretty much developed through being with printed matter. It is so important for students to see a full project or editorial and the context that the work lives in. You just don’t get this understanding with single images on Instagram. Working with printed matter develops skills in editing, sequencing and how an audience will engage with their work.”

So how does Murray collect? “I’ve obtained most of these books from either Village, an independent bookstore in Manchester, or at Offprint back when it wasn’t a fancy thing,” he says. “Most books these days, even small-scale things, are at least 50 pounds, which is such an inaccessible price. Magazines too! I haven’t got so many new books lately as I still have a lot to look through.” Murray is clearly a healthy collector, in the sense that he’s truly intentional with his additions – also because the surfaces of his shelves are flat and thus perfect for all the delicate paper. Instead of bookshelf wealth (using your books as a display of success), this is bookshelf health.

The house’s second floor – with the couple’s bedroom, elegantly tiled bathroom and generously sized office-cum-studio – is almost entirely dedicated to references and research behind Murray’s new book project, which will examine the relationship between fashion image and domestic space. Various Vogue Hommes International, Versace Magazine and Arena Homme + lay inside cardboard cases, waiting for their turn to be scanned into facsimiles for the book. “I’m tracing the history of fashion photography from the 90s onwards through imagery or editorials, from magazines or commercial commissions that are set or staged in homes. Whether it’s fashion photographers or photographers working in a fashion context – these boundaries have shifted a lot – how do you even categorise fashion today?” Murray asks.

Murray grabs a stick in the office that he attaches to a hatch in the ceiling, and down comes a ladder leading up to a loft. We crawl up into a vault dedicated to magazines only. “The first magazine I ever got was The Face at the newsstand when I was around 16,” he says. “I would collect them and have my mum and dad drive them up to university and back home every summer, boxes and boxes of them.” Murray’s loft has more or less the complete run. He also has the second issue of Joe’s, a magazine that stylist Joe McKenna did in the early 2000s – “this format is beautiful, but goes against my whole accessibility thing” – the magazine only lasted for two issues.”

Back on the railroad, this time together, we are headed back into Manchester – more precisely to the Manchester Met uni library, to explore more of our shared interests in libraries, especially those outside of the capitals. Murray claims they’ve got one of the best artist book collections in the UK. “Like you, I’m interested in who has access to collections and libraries. Manchester Met is a fantastic collection and so few people know it exists and that it is all open to the public,” he says. Murray steps into the library as if it’s his own, and there’s no one else there. Striking shelves with catalogues of some of the most seminal contemporary fashion exhibitions are held in acid-free boxes or Margiela-esque white paper pouches, labelled with a fuschia pink dot and an inventory number written in pencil. Lastly, Murray pulls out Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations with a sun-bleached price tag: £1.75. Now that’s accessible! Seeing Murray with books, whether with his own collection at home or with this external one, I’m reminded of one of the library’s purposes: as birthing rooms of the future. And on platform two, we close the book and Murray jumps back on his train of thought.