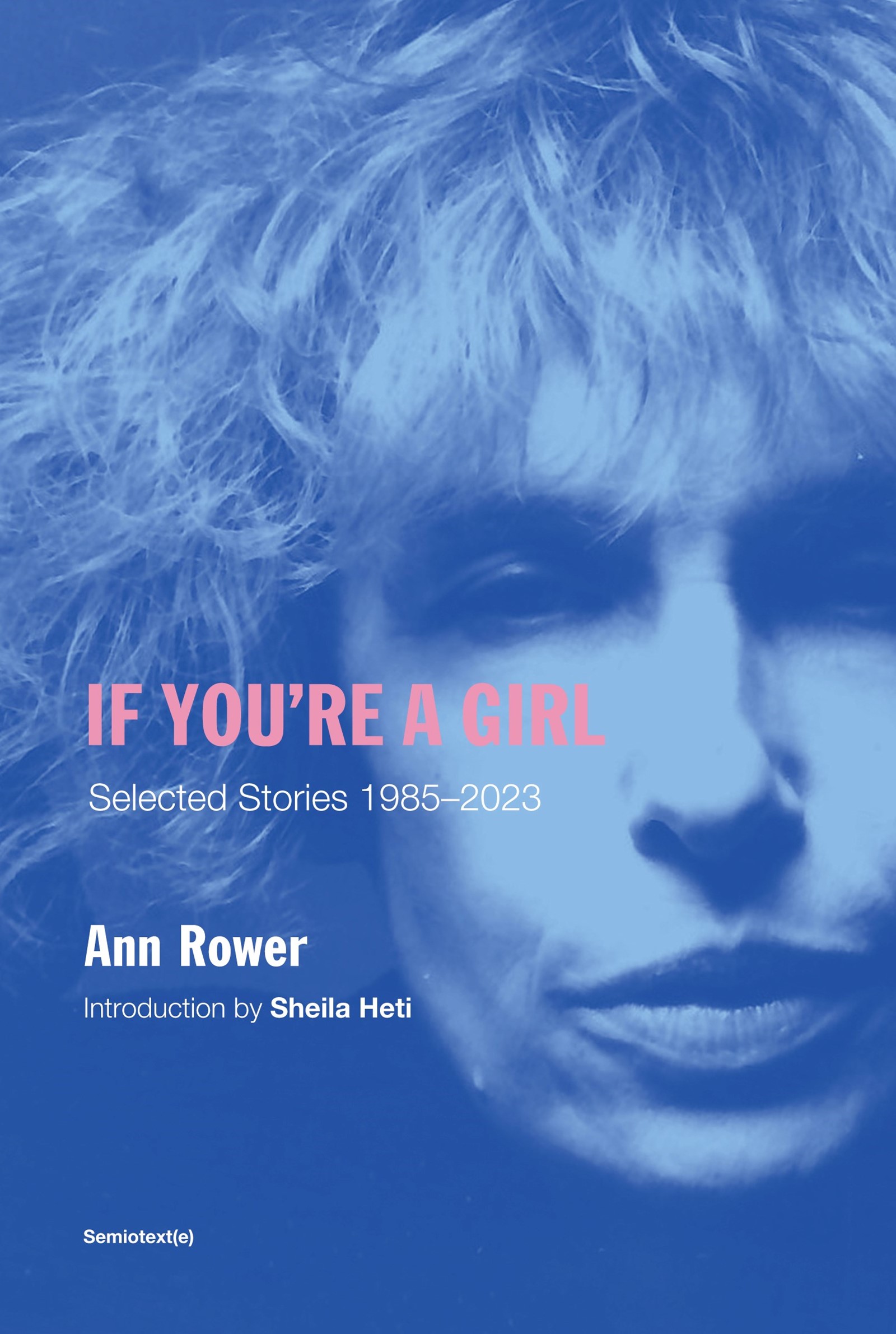

Ann Rower’s If You’re a Girl was first published by Semiotext(e) Native Agents in 1991. It was Rower’s first book, and Native Agents – the series established by Chris Kraus as an antidote to Semiotext(e) Foreign Agents’ penchant for French male writers – was in its first year. Rower was then 53, but she was firmly established in the downtown scene as a writer, with stories about everyone: she made plays with Francis Ford Coppola, danced under the tutelage of Martha Graham, attended a protest with Eileen Myles, toured with Kathy Acker and Lynne Tillman, and kissed (and subsequently fell in love with) Heather Lewis under a pink sodium street lamp. Her stories stopped when Heather committed suicide in 2002. Two decades later, Rower entered her eighties, signed a new book contract with Kraus, and started writing again.

The expanded edition of If You’re a Girl has dozens of new texts written over one long summer in 2023. Rower’s voice feels unchanged, ringing with gossipy humour and the hot arousal that stirs in the erotic act of remembering someone or something. Pain and loss hang not far behind the joke, but such is her rhythmic command of syntax that the punch line hits with a double beat: after laughter comes tears. Her manner is unflinching.

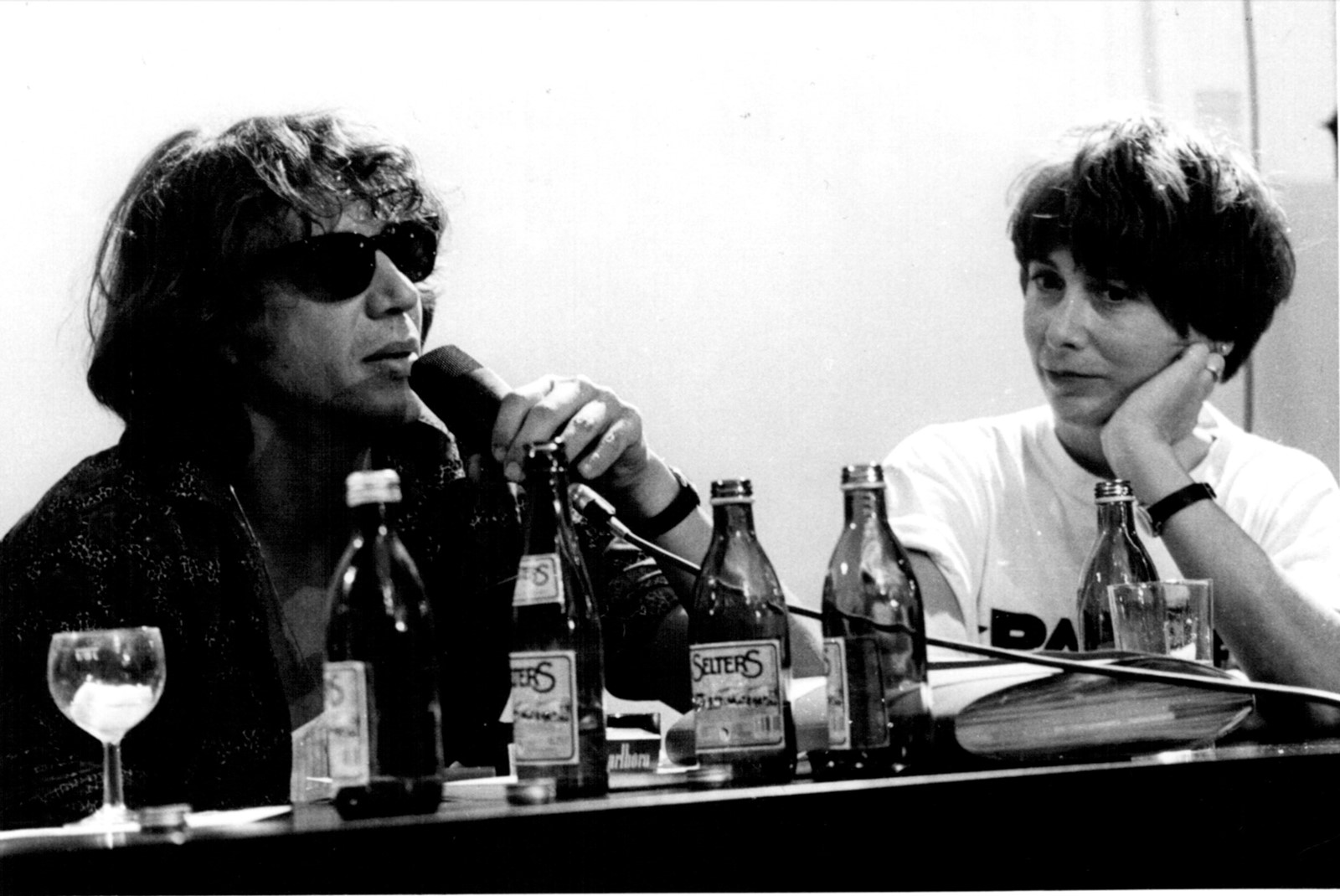

Kraus and Rower go way back; as Rower writes in the book, “Chris is the only person I’ve ever seriously collaborated with … Chris did many great things for my life, my well-being”. Their respect and affection for one another is palpable. Below, the ladies discuss what it means to be a girl, why transfiction is a better term than autofiction, how talking dirty in your eighties is the last taboo, and the big daddy of them all: transgression.

Chris Kraus: When you first started putting the book together, you were gonna look through your archives and choose some older stories that were left out of the original volume. But then you started writing more and more and more. About a third of the stories in the book were written in the last couple of years! So what happened?

Ann Rower: I aged. I aged out of shame, embarrassment, filter, everything. In other words, by the time I got to 85, it didn’t matter what people thought. Now I can say anything.

CK: At what point did you decide to jettison the idea of foraging for old material and just write new stories?

AR: It really wasn’t a decision. What happened is that I started doing physical therapy and somebody touched me. During the pandemic people didn’t touch. And my physical therapist touched me, just a little bit, very lightly. It made a huge difference. He also treated me like a writer. He would ask me – because I told him I was scribbling at night in my journal – how are your essays coming? It made me feel like a writer again, which I hadn’t felt like in 20 years because I hadn’t written anything new.

Then this friend came to my house with the first volume of If You’re a Girl, which she’d found clearing out the flat of her partner who’d died. There were stories in there that we hadn’t used in the original and that’s when I got in touch with you. We talked and you sent me the contract the next day. So I realised that was a story: it was the story of the stories and how they came to be. I wrote about that and for the next three months, I didn’t stop writing. They just came out. And then they stopped coming.

CK: Your stories have always felt to me like Russian dolls or Chinese boxes: there’s always the story within the story and you chase them down to the very end.

AR: Like Richard Hell said: ‘hungrily’. Good word.

CK: It’s amazing the way your style remains intact but the circumstances you’re writing about are totally different. Your writing was always daring and brazen and unfiltered but it seems incredibly transgressive that you apply this mouthy, jokey, post-New York style to the circumstances of being 85 years old. At one point you joke about calling your book If You’re an Old Lady. Do you think writing candidly about life in one’s eighties is one of the last taboos?

AR: It doesn’t feel that way to me but it seems when people talk about it they clear their throat, you can tell it’s a little awkward. I think people are not comfortable with women ageing in America. It’s really serious.

Isabelle Bucklow: And simultaneously there is this revival of interest in the idea and experience of girlhood. In the book, you move between ‘the girls’ ‘the ladies’ and ‘the women’, but you stuck with the original title. Can you talk about that decision?

AR: Yes, this reaction to people not wanting to say girl and insisting we say women which is, I don’t know, not such a good word. I’m not sure about ladies, except if you’re an old lady, and we end up back with ‘girl’ again, which is a good word. ‘If you’re a girl’ was originally from a song about getting raped, getting sexually assaulted. The hook was: these things just happen if you’re a girl.

“I aged out of shame, embarrassment, filter, everything. In other words, by the time I got to 85, it didn’t matter what people thought” – Ann Rower

IB: You mention how ‘if you’re a girl’ could be formed as a question now rather than a statement.

AR: Maybe it’s a question for everybody, because I don’t really know what being a girl means. I never felt like a girl, I never felt particularly feminine. I enjoyed my feminine parts but not necessarily [my] ‘femininity’. The fact is it’s not just writing about being in your eighties, but also writing about sex in your eighties. Talking dirty in your eighties is a big taboo. Since I’m by myself all I can do is write about it.

CK: The ghost of your late partner Heather Lewis runs throughout the book. At one point you were going to write a book about your lives together and then you abandoned it, but the memory of Heather comes and goes throughout all the new stories. Do you think sideways is the best way of addressing volatile topics?

AR: I guess that’s the right word, as opposed to directly head-on? Maybe I’m afraid to do it any other way. I don’t feel like I’m choosing a method or technique, that’s just how I do it, it just comes out sideways.

CK: You have this incredible strategy (and now you're going to say it’s not a strategy!) of telling difficult truths through deflection, refraction, apology. By playing dumb you get to be transgressively brilliant and accurate. Are you conscious of doing this?

AR: Once again it’s not a conscious choice. I like the feeling of writing about difficult topics and it’s more comfortable to approach them tangentially. Maybe that says a lot about me and my life.

CK: Transcribing other people’s voices has always been a big part of your work. There’s the essay that you wrote for the first edition called Transfiction, about the way following the rhythm and sounds of real voices is the best way to achieve an imperfect accuracy. Imperfect because the transcriber will always add or leave something out.

AR: I was doing all this transcribing at the same time I was working on a little play for The Wooster Group with Ron Vawter and Lizzie Borden. It’s very, very painstaking work because it feels important to get it right, every time they said ‘mmm’ or ‘urrr’ I wanted to put it in the right place. But Lizzy at the same time was writing a fictional story, and we were inserting the real dialogue into it. So that's where transfiction sort of came from. Someone pointed out to me, that’s what people now call autofiction. I’m not sure it’s exactly the same …

CK: It should have been picked up instead of autofiction. I think transfiction is a much better term, because there’s a pun in it too – to be transfixed.

“No person’s voice is ever one thing but an amalgam of all the other voices that they’ve been around and heard. We’re all collages of other people” – Chris Kraus

IB: It makes me think of something that Chris has spoken about elsewhere of being so transfixed by and immersed in a book that the author sort of enters your body and gives voice to your innermost thoughts. When transcribing, you let a voice flow through you. As you write, “You always fall in love with the voice you’re transcribing.”

CK: It’s something like a palimpsest, no person’s voice is ever one thing but an amalgam of all the other voices that they’ve been around and heard. We’re all collages of other people.

Richard Hell emailed something great after reading your book: “It gives me the sense of life as not being individual, but rather webs of relationships and happenstances.” Do you think that people are best revealed by following all the strands of a story?

AR: I do. Webs is the important word there, and happenstance, because from the beginning of this book, I felt that serendipity played a huge part in the way things happened: I found the physical therapist by accident, my friend found my early version of the book by accident. I’ve always cherished accidents. I think I believe in that if I believe in anything.

The expanded edition of If You’re a Girl by Ann Rower is published by Semiotext(e), and is out now.