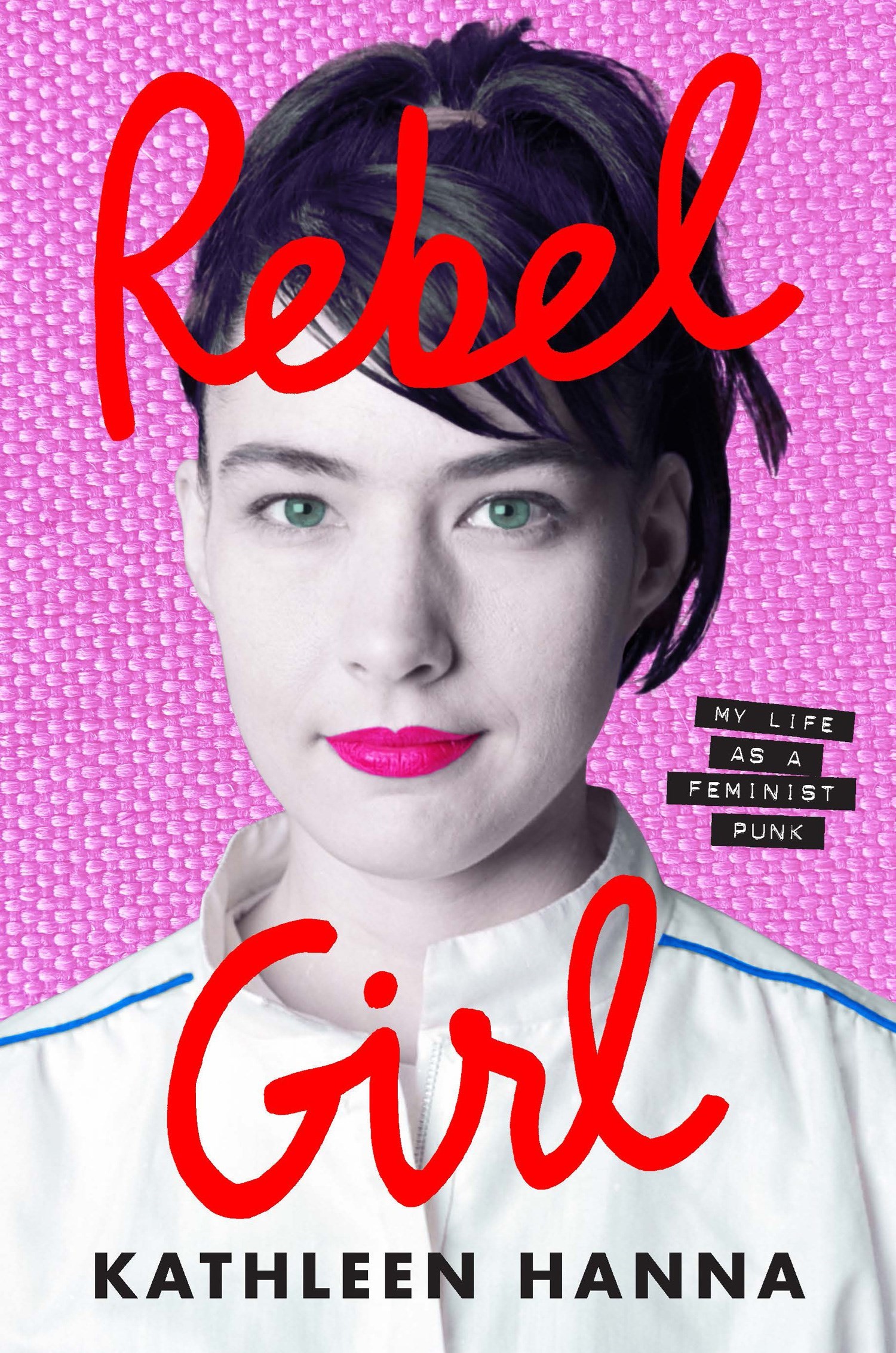

“To me, it’s not like a rock history book or some shit,” says legendary front-woman Kathleen Hanna about her memoir Rebel Girl. “It’s more a coming-of-age kind of story." A powerful, whip-smart reckoning with her life and work in pioneering feminist punk band Bikini Kill, and later Le Tigre and The Julie Ruin, Rebel Girl is a love letter to Hanna’s bandmates and the many people who lit her path as an artist. (Though there’s plenty of rock history in its pages too, from tender memories of friendship with Kurt Cobain – Hanna’s drunken graffiti famously inspired the title of Smells Like Teen Spirit – to falling in love with her husband, Adam Horovitz of the Beastie Boys.)

Coming of age comes across as an ongoing process, a series of epiphanies – whether it’s discovering a love of performing, encountering vital feminist texts, starting a gallery and a band, or helping build a grassroots feminist movement in riot grrrl. There’s an early meeting with Kathy Acker, who advises Hanna to start a band, and friendships with Joan Jett and Kim Gordon, who recently appeared on the cover of AnOther Magazine. Then there are the many zine writers, artists and musicians, as well as survivors who contributed to Hanna’s story and creative ferment.

Hanna’s style is vivid and forthright, with a lightning sense of humour that throws a cleansing light on the pain and violence she has also experienced. “I want to say all of this stuff now, so that I can move on to my next career,” she explains. “I can do whatever I want because I have sort of wrapped that past up and put a really beautiful bow around it.”

Laura Allsop: How did you start gathering together and distilling the material from your life for the book? Did you write chronologically or was it more impressionistic?

Kathleen Hanna: It was definitely nonlinear. For most of my life, I’ve journalled every day, since I was probably 17. And I just write down titles or things I overhear, or funny wordplay. I always have a page of weird titles going, that could be song titles, or book chapters, or band names. I started conceptualising the book and thinking, what would the [chapter] titles be? Some of them were shorthand for events in my life. I always say “Benjamin Franklin’s glasses” when people ask me about the Smells Like Teen Spirit thing, because in my head I feel like I found Benjamin Franklin’s glasses in the garbage. And everyone’s like – you’re the girl who found Benjamin Franklin’s glasses! I’m like no, I’m a musician, I’ve done all this stuff! I’ve travelled the world and been in museums. And they’re like, yeah, but you’re the girl who found Benjamin Franklin’s glasses. So I wrote all those titles down in a line and then I would just go to work.

LA: I wanted to ask about your literary influences and if there were other musicians’ memoirs you thought about as you were writing?

KH: I read a couple that I hated but I won’t say what they were because I’m not that guy. But the people whose work I would refer to mainly were Brontez Purnell, who has written fictional memoirs, but really in his own voice, and very fearless. I love this one book Johnny Would You Love Me If My Dick Were Bigger; I also love Since I Laid My Burden Down. I was like, I can’t keep reading these because it’s just setting the bar too high. But he reminded me to not be afraid, or ashamed, and that everyone’s story is interesting. And then of course, Viv Albertine – her second book, To Throw Away Unopened, even more so than her first, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. [It’s] about her relationship with her sister, which was enthralling, her mom and her daughter and the process she went through of deciding to get a divorce and what it means to be ageing. She’s a really strong writer and there were sentences that I just lingered on. Brontez as well. His books are so dense, like a flourless chocolate torte with so many perfect sentences over and over you feel like you’re being stabbed in the heart by beauty.

LA: Did you keep the book to yourself as you were writing, or show it to people along the way?

KH: I kept it to myself for almost the whole time, the only person who saw it was [author] Ada [Calhoun]. The first comments I got back were from Ada, and I feel really thankful because we’re friends and I think she’s honest, but gentle, and was really excited about the project, which made me excited about it. Then when it was pretty near done, I sent it to Mimi Thi Nguyen, who’s mentioned in the book. She’s a writer who I really respect who wrote this wonderful essay about race and remembering of riot grrrl, the re-historicisation that whitewashes women of colour out of history but puts the nostalgia spin on it and takes out any racism or homophobia or classism. I got some great comments back from her. And then I sent it to Tobi [Vail] and Kathi [Wilcox], my bandmates in Bikini Kill, mainly because they’re in so much of the book. That was about it. I mean, my husband didn’t read it till like two weeks ago.

LA: You were the subject of a documentary, The Punk Singer, in 2013 and your archive is at New York University. After these experiences of archiving and contextualising your work, how was writing your memoir different?

KH: This just felt like the end of a trilogy. The documentary was focused on certain things. There are a lot of issues I had with it, though I’m happy it got made at all. I’m making one about my uncle [Darcelle XV] right now, and it’s impossible. He was the oldest living drag queen and had the oldest continuously running drag club in the world. His life story holds a lot of meaning for me. But the fact that [The Punk Singer] got made at all was kind of a miracle. I was sick during a lot of it, so a lot of my memories aren’t the best because I wasn’t feeling well, even though I look pretty cute – looks can definitely be deceiving! There was a point where I said something like, I could never tell my full story because nobody would believe it. In a way, I felt like that was the beginning of the book. I’m just going to say it all. And the archiving was a part of that process, because I had looked at and grappled with that material, I had gone down memory lane in my head.

The thing I kept out of the archive was all my journals, and so I kind of had to process those. I have hundreds of journals. While they were very beautiful and had lots of cool pictures glued in them and paintings and drawings, and I thought they were going to be a wealth of information for writing the book, they didn’t help me at all, they were all about internal stuff I was feeling. It was tonnes of quotes and shit I was trying to write about theory that was embarrassing and crushes I had. Now I’m going to have to have some kind of party, where I burn them in a fire. But the archive really was the first step of the process, the film was the second step, and then the third step was the book. And I feel like – I’m done, I’m free.

LA: I would love to know what the next chapter holds?

KH: I want to tour with Bikini Kill – as L7 said – till the wheels fall off, for as long as we can. It’s very healing to go from being in a band that was constantly harassed to being in a band where people are like, crying the whole time and screaming all the lyrics and dancing and having a great time. We just got back from Latin America, and it was absolutely thrilling. Whereas maybe in the States, I saw some of the less idyllic versions of riot grrrl, whereby, you know, white middle-class women played the oppression Olympics to the detriment of everyone else, I got to see that in certain places in South America, riot grrrl was a real site of resistance – is still. That was very gratifying, especially after writing this book, to see the way that my band’s music and other bands’ music had really been a part of something that continued to grow, as far away as Santiago, Chile. You know, in Argentina, they’re going through this horrible shit with this right-wing president. To see people who are in that situation screaming political slogans at shows and really participating … it just felt great.

Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk by Kathleen Hanna is published by William Collins, and is out now. Bikini Kill will play at the Roundhouse in London on 12 June 2024.