With new titles being released by Philippa Snow, Olga Tokarczuk, Constance Debré and more, here are ten books to add to your reading list over the summer months

The only curatorial theme for this list is that these are recently published books. Though not all strictly contemporary – some are reissues and some are in translation – each title was either published over the past few months, or is set to come out over the coming summer. So it’s a list assembled by chance, through publishing calendars alone. Nevertheless, other uniting themes have emerged. Women making art is one; the compromises, envy, looking to others, constricting material realities, and freedom that can come with this. Desire, and the course it can chart for your life, is another. Also, the aftermaths of radical decisions and the metamorphoses that these decisions can prompt. Finally, there is a focus on those people who lead unconventional lives, and who create the bonds they want to have with others on their own terms.

Below, find our recommendations for the summer months.

Trophy Lives by Philippa Snow

It feels apt for Philippa Snow’s democratic critical approach that in buying Trophy Lives: On The Celebrity as an Art Object you also get to possess a reproduction of the transcendental Sam McKinniss painting of Whitney Houston, Star Spangled Banner. Brilliant cover aside though, with this latest book-length essay, Snow further cements her reputation as one of our most original writers on celebrity, art and culture. Perhaps it is partly because Snow studied at art school that her criticism feels generative; in her work, you often feel that something new, beyond the original subject of her writing, is being produced. Another particular joy of reading Snow is her ability to draw unexpected connections between her subjects, and to find new ways of seeing. “The arc of becoming a celebrity, with all the alterations to the self it tends to require, can look kind of like a horror story from the right angle,” she told AnOther.

Read our interview with Philippa Snow here.

Loved And Missed by Susie Boyt

In Loved and Missed, the seventh novel by Susie Boyt, an ageing teacher, Ruth, takes over the care of her only granddaughter, Lily. Lily’s mother Eleanor, Ruth’s only child, is in the grip of a severe drug addiction, and though initially an informal arrangement (Ruth takes Lily home after her christening, in exchange for a bag of cash), Ruth ends up effectively being Lily’s mother: a role she takes huge delight in, perhaps because of her estrangement from her actual daughter.

Similar to Vigdis Hjorth’s novels of familial estrangement, Boyt gives us only Ruth’s perspective for the vast bulk of Loved and Missed. This means that Eleanor never quite comes into full view – she feels nearly a figment of her mother’s imagination at points – and it emphasises the fact that each member of a family’s experience is only their own: “She’d tell it differently, of course,” Ruth says of Eleanor at one point, “but she wouldn’t talk to me.” The result is a beautiful, complicated novel about trying again, the thickness of friendship and the unconventional bonds that many of us build ourselves, both in the midst of a dysfunctional family and in its absence.

The Hearing Test by Eliza Barry Callahan

Eliza Barry Callahan’s debut novel begins, “I have a habit, since I can remember, of reading plot summaries of movies and books before watching or reading them.” Anyone who is also prone to doing this will know that most of these kinds of online summaries tend to capture, above all, the difficulty of communicating the experience of anything through plot points alone. It’s a fitting opening, then, for an astonishingly vivid, painterly novel, that’s acutely attuned to capturing the narrator’s daily experience, not just of losing their hearing, but of falling out of love and grappling with making meaning and art.

Read our interview with Eliza Barry Callahan here.

The Last Sane Woman by Hannah Regel

Hannah Regel’s debut novel, The Last Sane Woman follows artist Nicola who, experiencing a crisis of self, stumbles upon the letters of potter Donna who, three decades prior, seems to have been on a trajectory that (Nicola feels) eerily resembles her own. Donna’s letters are written to her friend Susan, who is in an unhappy marriage raising a young daughter. While Nicola’s is the connecting thread, any of the three women could be thought of as the novel’s protagonist, their perspectives and psyches intertwining, creating an effect that reinforces the fact that how you see yourself and others is always rooted in your own subjectivity.

Regel started out as a poet before turning to fiction, and the sharp aesthetic sense and ability to hold and distil a moment that characterises her 2020 poetry collection, Oliver Reed, are present here, too. But (to me at least) the strongest moments of the novel are where Regel lets her characters veer into camp, whether through their interactions, or expertly depicted scenes of weekends in the country with well-to-do friends. “WELL, SUSAN”, Donna exclaims in a letter to her friend, where she announces that she met a man and fallen in love. “You don’t think I have chutzpah?” Nicola asks her boyfriend Ben. “I think that you’re depressed, Nicola,” he replies.

The Last Sane Woman has been marketed as a novel about ‘art and envy’, and while it is that, it is also about the unique frustration we can feel over the holes in ourselves, and our desperate, and, ultimately, futile attempts to find a model on which to base the narrative of our lives.

Playboy by Constance Debré

There are different strategies of rewriting that different people will employ to protect themselves and their pride in the aftermath of a divorce or breakup. Victimhood is an easy one; most people can do enough harm to each other over the course of even a good relationship that there is usually plenty of material for this. Part of the appeal of Constance Debré’s much-lauded Playboy – the second of her novels to be translated into English, but chronologically the first that was published in her native France – is that there is little of this victimhood on display. In this account of a woman leaving her husband both to begin having sex with women and to pursue the life of a writer, Debre’s ‘I’ tends to eschew self-pity, and clearly egregious treatment is presented mostly in matter-of-fact terms. What results is a consideration of metamorphosis, motherhood and sexuality that feels bold and true.

Read our interview with Constance Debré here.

The Children’s Bach by Helen Garner

I was delighted to see that the great Australian writer Helen Garner was getting the reissue treatment in the UK this spring, but it was laced with that feeling of when you love something so much that you almost want to keep it to yourself. A titan in Australia but criminally under-read here, Garner is, if not my favourite writer, then the one who I return to the most, and so I did think: if she becomes everybody’s, will she still feel like mine?

That possessiveness, the feeling that she is yours, is also borne out of the extreme intimacy of Garner’s writing. Right from Monkey Grip – her first novel, which was published in 1977 originally and lifted in parts from her diary – you have the sense that you are laying around with her in a shared communal house in Melbourne, serenely watching the loose parenting, drug-taking and love affairs play out. I recommended her a couple of years ago on one of these lists; then, I said to start with Monkey Grip. Today, I think I will say start with The Children’s Bach, the most novelistic of her works.

The Empusium by Olga Tokarczuk

Forthcoming from Fitzcarraldo in September, The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story, is the latest of Olga Tokarczuk’s virtuosic novels to be translated into English. Set in 1913, it opens with tuberculosis-afflicted Mieczysław Wojnicz checking into Wilhelm Opitz’s Guesthouse for Gentlemen, a kind of convent for sick young men. As something dark and unsettling unfolds in the background, the residents sit around drinking the hallucinogenic local liqueur and weighing in on topics of the day, particularly gender. (Think interiors described as, “Very masculine: just imagine, marble, onyx, mahogany, real leather. A black-and-white floor, minimalist …”).

In their rigour and subject matter, Tokarczuk’s novels can tend to feel not of this time, and so it can be easy to forget just how funny and contemporary a writer she is. The Empusium is at its sharpest in its scenes of men talking about women, with lines like: “Women are more fragile and sensitive by nature … which is why they’re easily inclined towards ill-considered acts.” And, “In Mieczyslaw Wojnicz’s family world, the women had vague, short, dangerous lives, and then they died, remaining in people’s memories as fleeting shapes without contour.”

Hagstone by Sinéad Gleeson

Another rich novel about women making art, Sinéad Gleeson’s Hagstone is set on a remote island off the west coast of Ireland, where artist Nell lives an isolated existence creating work in dialogue with the landscape. On the brink of another harsh winter on the island, she is invited by the Iníons, a reclusive self-sustaining commune of women, to make a piece on their history. In the background of Nell’s life there are also two men – Nick, a famous American actor, and Cleary, an islander who has recently returned. (To the wider men of the island Nell is, “Not wife material … Thank fuck for that.”)

Gleeson herself is an artist as well as a writer, and this novel is intimately attuned to the material realities of constructing artworks, their meaning and reception, and the financial precarity of an artist’s life. Also the sometimes savage reality of rural, remote life, over an idyll of what it might be like. On one piece she writes of, “Looping wires around the trees, hoping branches would take the weight of the speakers. The possibility of electrocution.” Or, on a journalist describing Nell’s work as ‘moving’: “Her work was not meant to move people. All that she wanted, all that she asked of an audience was for them to be present, or curious.”

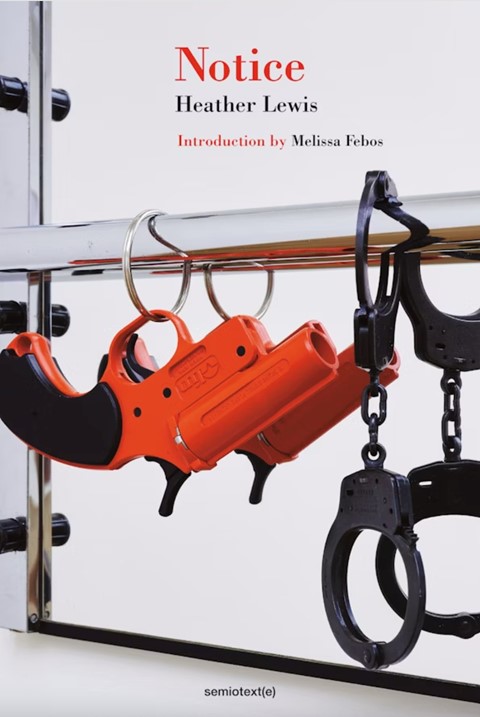

Notice by Heather Lewis

First published in 2004, two years after Heather Lewis’ death, and recently reissued by Serpent’s Tail and Semiotext(e), Notice has amassed a cult following over the years for its graphic, compulsive account of a sex worker’s descent into a sadomasochistic exchange with a couple. It is easy to get caught up in the pure violence of Notice – words like ‘stark’ and ‘brutal’ repeat through reviews and blurbs, and if you Google the book one of the first hits is a video by a YouTube reviewer (his channel is called CriminOlly) titled, “The most disturbing book ever is back in print!” However, for me, Notice is compelling most of all for its depiction of desire as a force which can override comfort, safety and even free will, and for some of the best, most evocative writing on sex that I have read.

Mother State by Helen Charman

I started to type that Mother State, the eagerly anticipated debut from the writer and academic Helen Charman, was ‘slender’, then looked again, slightly perplexed, at the proof on my desk. In reality, Charman’s “political history of motherhood” is pretty substantial. But how could it be, when I tore through it over a couple of days like it was a thriller? Some of this is owed to Charman’s invigorating style and to the clarity of her thought. She writes beautifully, with a great sense of pace, and has the intellectual confidence and generosity to make her arguments clearly (and convincingly); there is no jargon or convoluted, meaningless, language. (For a sense of this style, I have been recommending her conversation with Jaqueline Rose).

In Mother State, which is out at the end of August, Charman weaves anecdotes from her own life deftly alongside a great catalogue of references – high, low, historical, academic, and anything in between. A book which could also be read as a history of feminist thought through the past few decades, I especially appreciated its full understanding and contextualising of Ireland, the North of Ireland, and its relationship to Britain.