Queer individuals and communities in the Arabic-speaking region have long had to contend with, as well as push against, either the negation of their existence or the instrumentalisation of their plight. Our realm of the everyday is punctured with the ordinary violence of state and religious formations; and shifting our gaze towards an elsewhere only ever points us to imperial tactics aiming to alienate us from, or have us turn against, our kin.

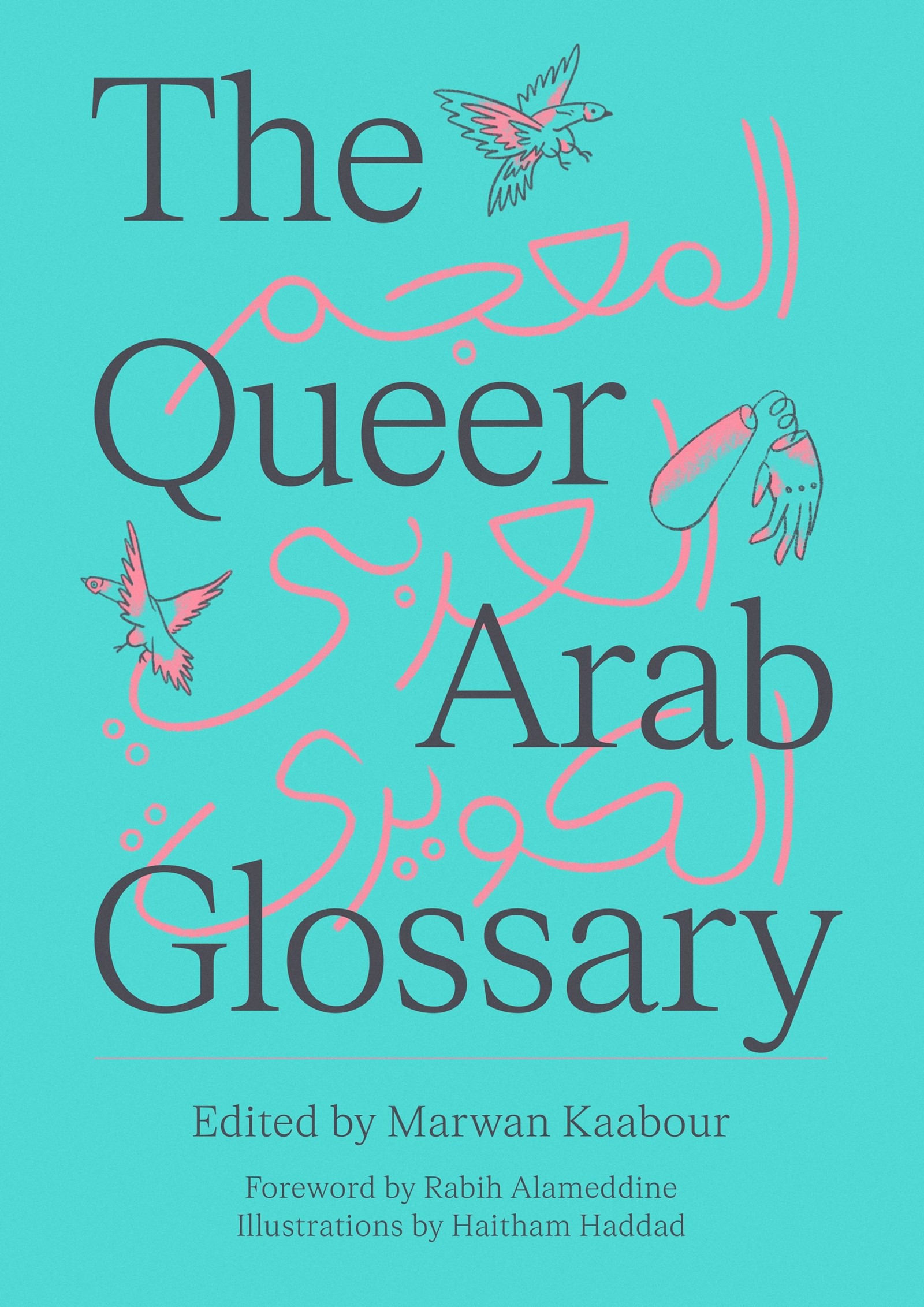

The Queer Arab Glossary, edited and designed by Beirut-born graphic designer and visual artist Marwan Kaabour, conjures community, resilience, and breathing space in the form of a book. As a project and offering rooted in archival care and memory work – there is emphasis on preserving local queer slang of the past and the present, as well as engaging the manifold cultural artefacts and phenomena that have shaped us – it remains refreshingly committed to laying bricks towards a future of recognition and emancipation. The Queer Arab Glossary is but a beginning, but one that is brimming with aliveness and possibility.

Below, Marwan Kaabour tells AnOther about the thinking behind The Queer Arab Glossary.

Edwin Nasr: At the beginning of this was a digital repository you created and manage, Takweer. It primarily operates through Instagram and continues to enjoy great success. Could you tell us more about this platform and how it informed the shaping of The Queer Arab Glossary?

Marwan Kaabour: Takweer is a virtual space where I collect, archive, research and celebrate queer narratives in Arab history and pop culture. It began in September 2019, mainly as a research space for me to explore ideas and themes I was interested in. Little did I know that I was (accidentally) building an archive. I basically comb through Arab books, articles, films, television, magazines, art, memes, etc in order to spot a queer narrative. Once I do, I research it for context, and then share the post on Takweer in both Arabic and English. My background is in graphic design and story-telling, and that plays a crucial part in how I present material on the page.

The page has now grown to over 22,000 followers. Takweer was always meant to be a broad space of exploration that leads to more focused projects, and The Queer Arab Glossary is Takweer’s first realised project, with language being the focus. I constantly interact with the page’s followers, many of which speak Arabic dialects I am not familiar with. They would use queer slang, which I would enquire about, and that curiosity led me to want to discover more, and build a linguistic mapping around queerness across the Arabic-speaking region.

EN: What then pushed you to envision The Queer Arab Glossary as a book, rather than an evolving digital platform?

MK: The quick answer is that I love making books. In my design practice, I am primarily a book designer. It’s a format I know intricately and am able to think through. I also wanted to produce a reference book that can exist in personal and academic libraries for the future. I envisioned it as a continuation of the long history of Arabic glossaries (mo’jam) that I’ve encountered in my childhood. With that said, I do feel the project lends itself naturally to a digital space that is evolving and changing, just like language does.

EN: One particularly compelling aspect to The Queer Arab Glossary is its structure – part dictionary of slang terms used by or for queer-identifying individuals and communities across the Arabic-speaking region; and part collection of newly-commissioned essays reflecting on histories and modalities of queer world-making as well as ongoing struggles against state violence. How did you pick the contributors?

MK: The way I envisioned the project changed and evolved as it grew. I initially wanted to produce a small glossary of terms, but when I ended up with over 300 entries, it was clear that I had a bigger undertaking on my hands. It was integral to me that I situate and contextualise the book in today’s world, from different vantage points. The ‘Arab world’ is made out of endlessly diverse communities, as is the queer community itself, so I set out to find a variety of diverse Arab voices, who can expand on themes of language, slang, and queerness from their own unique perspective and area of interest. The eight contributors range from writers, poets, researchers, community organisers, translators, musicians, and novelists. They hail from different parts of the Arabic-speaking region, with most having grown up in it, and others in the diaspora. I hope that the experiential multiplicity of the contributors’ allows for a nuanced and necessarily complex reading of the queer Arab community.

EN: Slang terms used by and for queer-identifying individuals tend to be difficult to track and make sense of specifically because some were created for the purpose of concealment and opacity; others for intra-communitarian referential purposes understood only by its members. How did you manage to collect so many from different geographical contexts?

MK: One of the joys of having a project like Takweer, is the way it allows me to connect with people from all across the Arab and queer communities. Takweer’s followers have always been honest and generous with their feedback, advice and input. When it came to sourcing the initial ‘data’ for the glossary, it was only natural that I would resort to speaking with people who use these words and terms themselves. As it is an Instagram page, I used the built-in ‘submission’ sticker to ask the page’s followers to submit words they use or are familiar with. I asked them to specify which country or dialect that specific word is used by, and to provide as much context as possible. I repeated that exercise multiple times, which is how I ended up with my initial data, which I then organised in a sprawling spreadsheet. Having followers from all over the Arabic-speaking region meant that the submissions reflected that diversity.

Over the next two years, I switched to having one-on-one interviews with individuals from different geographic contexts, where we would go through the compiled list of that region, and discuss each entry. I made sure to speak to people from different parts of the same region, but also of diverse socioecnomic backgrounds and gender identities. I kept on doing that until I felt there was enough context and nuance to each entry. I then roughly translated all the entries myself. The final and very crucial step was bringing in Suneela Mubayi, the glossary’s brilliant editor, who was able to give each entry much-needed historical and cultural depth, as well as refining the language and translations further.

EN: The Queer Arab Glossary seems especially relevant at a time during which our existence is being erased or weaponised for the justification of ongoing genocidal campaigns. How do you tie this project with the ethical and political imperative to stand in solidarity with Palestine?

MK: The necessity to uphold Palestine’s right for liberation and self-determination is one that I carry in my being in every step. One of the many tools of manipulation and erasure that is used against Palestinians is pinkwashing, which aims to portray Palestinians, Arabs and Muslims as hateful and homophobic barbarians who are incapable of embracing queer people in their communities. The Queer Arab Glossary obliterates that assumption by not only showing that queer people have existed and thrived, despite the challenges, at the heart of our communities from the early days of this region till today, but also shows how Zionists have weaponised queerness against Palestinians as a method of further subjugation. Adam Hajyahia’s piece in the book Are You a Pan-Arab Nationalist or Just a Man Who Sleeps With Men? illustrates that beautifully.

EN: You dedicated the book, among others, to your ‘queer comrades’ – a term we heard a lot following the tragic suicide in 2020 of militant Sarah Hegazi, who had to flee to Canada following her brutal arrest and torture at the hands of Egyptian security forces for the supposed crime of waving a rainbow pride flag at a Mashrou’ Leila concert. What makes a queer comrade?

MK: They are people who expand and challenge our understanding of what being queer is. They reject the limitations of identity politics, and firmly place queerness in a space that considers the humanity and liberation of all. We laugh and joke with them, we show each other boundless love, we dance and sweat, and then we go to battle together.

The Queer Arab Glossary by Marwan Kaabours is published by Saqi Books, and is out now.