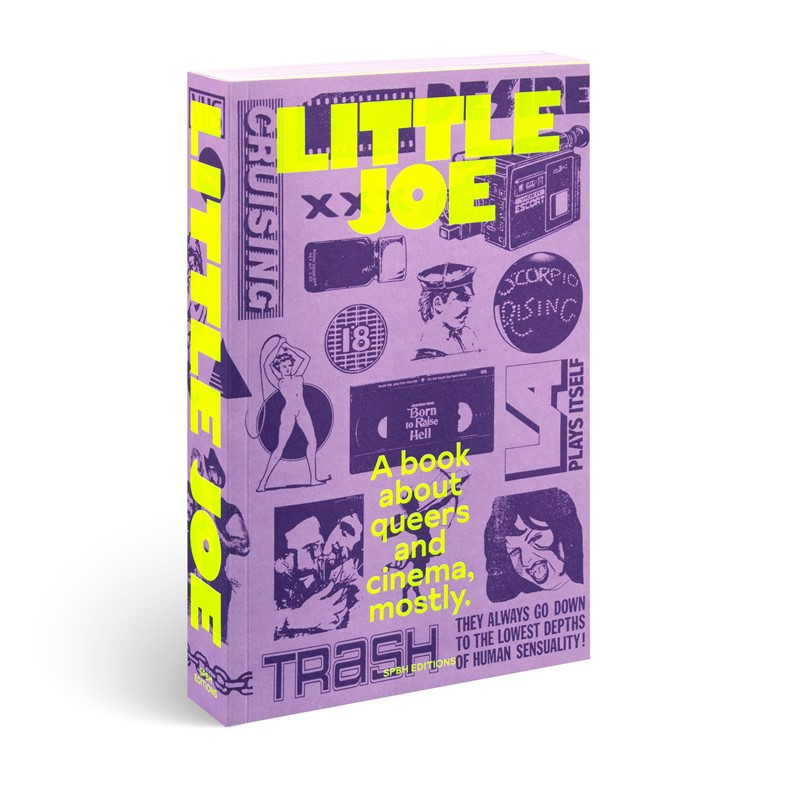

As the cult magazine publishes a new bible of queer cinema, Little Joe picks six queer cinema classics from the book to add to your watchlist

If there were a bible of queer cinema, Little Joe: A Book About Queers and Cinema, would be it. Discussing over 100 seminal titles, the new compendium of interviews, essays, recommendations, archive imagery and beautiful illustrations is a cinephile’s wet dream. Sometimes quite literally; the book never shies away from exploring the murky territory between arthouse cinema and pornography, along with pieces like a guide to cinema during the early days of Aids, and interviews with underground heroes including George Kuchar, Rosa von Praunheim and George Earl. Taking inspiration from Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon, the salacious stories behind the screenplay a crucial role in the editorial direction.

Little Joe started out as a magazine, running from 2010 to 2021, and was created by designer and cinema obsessive Sam Ashby. It was a beautiful risograph object that quickly became both cult and collectible to those with an interest in queer culture or film more broadly. (Ben Whishaw: “I cherish my copies of Little Joe.” Same.) There was a playfulness to the publications: stickers or micro-zines might fall out of its pages. They even held a scratch-and-sniff screening of John Waters’ film Polyester. The magazines – six issues in total – all sold out, are now famously hard to come by. Thankfully, Ashby has generously collaborated with Mack Books and SPBH Editions to make some of the best content accessible in book form.

Below, to celebrate the publication, and the sexier side of queer culture this Pride Month, the team behind Little Joe selects the queer cinema classics that best capture their ethos.

A Bigger Splash (1973)

The front cover of the first issue of Little Joe featured Peter Schlesinger swimming naked in Jack Hazan’s film A Bigger Splash (later remade). The film was also the first title that Little Joe screened IRL, in New York. Made in what its director describes as “experimental times”, it’s a dream-like, feature-length documentary focused on the breakdown of the relationship between painter David Hockney and his then-partner Peter. To make the film, Hazan essentially hung around the artist until he conceded. “He was not precious about his privacy in any case. He’s very democratic and if he likes you, he’ll treat you as he treats himself,” the filmmaker tells Little Joe. However, when the film was released – deeply intimate and unprecedented in its representation of ordinary gay life – it was both socially controversial and upsetting to Hockey, who reportedly went into a depression for two weeks, feeling exposed at being captured so closely. Now, however, the artist “looks at [the film} as history”, according to Hazan. “His life was a love story. The film was a love story because that was what he had made it.”

Taxi Zum Klo (1980)

Translating as “taxi to the toilet”, this is a cruising masterpiece, if such a genre exists. Director Frank Ripploh’s authentic, semi-autobiographical film follows the story of a school teacher by day who ventures out in search of anonymous sex by night. In tracing one man’s day from classroom to glory hole, it plays on society’s worst fears about gay men at the time: “think of the children!” The heart of the film, according to Ripploh, is “about the struggle that is love and the difficulty of keeping a love,” a conundrum that occurs when the film’s protagonist finds a relationship that tests his desire for domesticity against his desire for sex (yes, there is a piss scene). The film was seized by US customs and eventually banned by the UK’s Video Recording Act of 1984, falling out of circulation. But when UK indie film distributor Peccadillo Pictures re-released it in 2011, a new audience discovered it as a film that is still relevant to a question many queers experience: to assimilate or not to assimilate, and do we really have to choose?

City of Lost Souls (1983)

The third issue of Little Joe featured an iconic image of punk star Jayne County on its cover. The image derives from City of Lost Souls, a low-budget German musical film directed by Rosa von Praunheim and performed by drag queens and transgender women, including County. As writer Bradford Nordeen explains in Little Joe: “Ostensibly, City of Lost Souls is about a Berlin pension run by an American transsexual starlet, Angie Stardust, who also manages the squalid diner downstairs, Hamburger Queen. That fast food dive is stagged by the pension’s boarders who, when we first encounter them, are doing anything but working [...] it is between these characters that the loose chain of events we typically call a plot will unfold.” At moments the film descends into chaos, or the comically absurd – like when Country’s character becomes pregnant. It’s a very fun watch.

Zero Patience (1993)

After Aids first hit North America, conjecture swirled as to how it originated (much like with the Covid pandemic). Enter the urban legend of “patient zero” – the Canadian flight attendant who reports claimed was responsible for spreading the epidemic. In true camp subversive fashion, Zero Patience takes this story and sends it up in flames, through the format of the musical. Written and directed by John Greyson, the film examines and refutes the urban legend, as we follow the story of 19th-century English explorer Sir Richard Burton meeting the ghost of the first Aids patient in a sometimes shlocky but almost entirely novel film. In Litle Joe its director names just one comparable title: “I was aspiring to [Derek] Jarman’s Edward II (1991) or Wittgenstein (1993) achieved so beautifully – but instead, because of budget and inexperience, I feel we landed more on the low-budget and somewhat clunky Rocky Horror side of the tracks.”

BloodSisters: Leather, Dykes and Sadomasochism (1995)

When a film is protested, that’s often a good sign, or at least, Little Joe might argue so. This documentary film directed by artist and filmmaker Michelle Handelman hones in on the lesbian BDSM and leather scenes in San Francisco in the mid-1990s (the same scenes that Catherine Opie famously documented, as well as the magazine On Our Backs). BloodSisters was subject to protests by the American Family Association as part of efforts to defund the National Endowment for the Arts, from which the film's distributor Women Make Movies received funding. At the time, it was a radical look behind the curtain of sexual subculture (long before harnesses were seen on catwalks and kink went “mainstream” in advertising.) Today, the film reads more like a historical document of a movement and a group of people who ripped apart the rule book when it comes to sex and gender, kink, love, and activism, and entirely rewrote it. It’s a far cry from the longing lesbian love stories that have made their way onto our cinema screens of late.

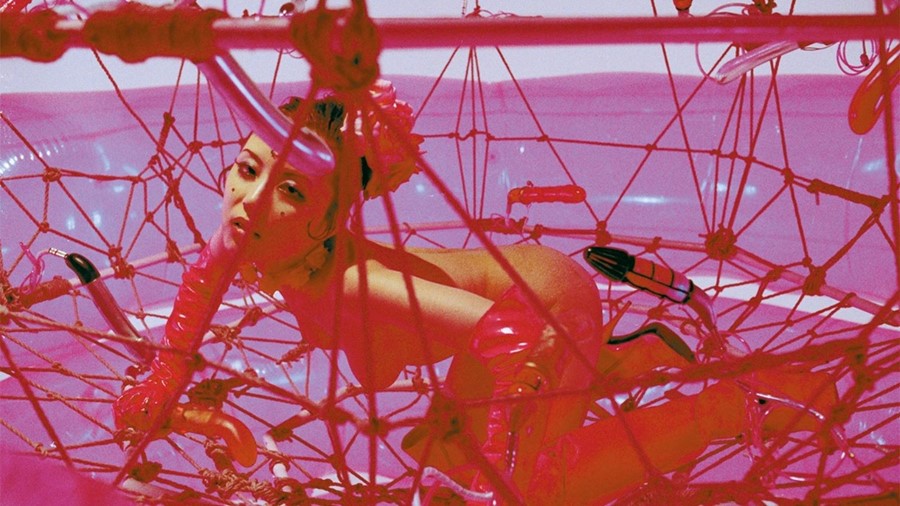

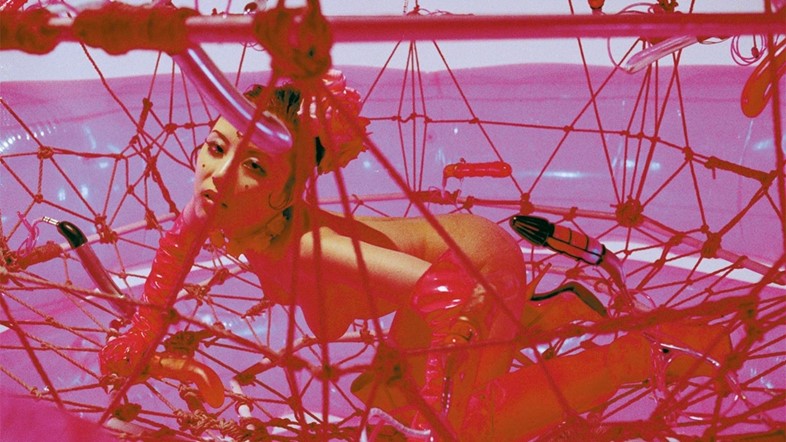

IKU (2001)

When Taiwanese-American experimental filmmaker Shu Lea Cheang’s film IKU premiered at the 2000 Sundance Film Festival, critical reception was poor. The first pornographic film ever screened in the festival, it was marketed as a “Japanese sci-fi porn feature”. Its storyline follows Reiko, a sex robot programmed to accumulate sexual experience, who goes through seven body types to experience a variety of couplings and collect “orgasm data”. Inspired by Blade Runner, only more psychedelic and much more explicit, the film explores digital politics and queer sex positivity, through the female gaze. As artist Liz Rosenfeld, one of Lea-Cheang’s collaborators puts it in Little Joe, after they saw IKU they felt “excited. Hopeful. Ready to fight. Ready to fuck.”

Little Joe: A Book About Queers and Cinema by Sam Ashby is published by SPBH Editions, and is out now.