As Apartamento reissues Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s Tokyo Style, we explore the cultural impact of the book, and how it challenged the picture-perfect myth of Japanese minimalism

First published in 1993 after the collapse of Japan’s infamous bubble economy, photographer Kyoichi Tsuzuki’s book Tokyo Style showcases the unfiltered realities of a handful of ordinary people living in one of the world’s most fetishised cities. Unsettled by the misguided international perception of Tokyo’s 33 million-strong population living in uniformly minimalist, traditional Japanese homes, Tsuzuki spent more than two years traversing the many neighbourhoods of the country’s capital on his green Honda 5cc scooter in an extraordinary effort to capture authentic homes that he felt truly represented the city’s residents.

More than three decades have passed since Tokyo Style’s original publication, and now, interiors publisher Apartamento has revived the cult classic with a reissue that includes a moving introduction by Barry Yourgrau and a new afterword from Tsuzuki himself. Reflecting on the cultural significance of this body of work both then and now, the photographer and former Popeye and Brutus editor writes, “In those days, the media only showed unusually luxurious living spaces that were the bastard children of the bubble economy, while more familiar homes of ordinary people were kept hidden. I realised that it was my life’s work to pursue the truth of how most of the world lived. It was my job to depict this reality, which was not a major one, but a majority one. Now, 30 years later, most of the media is still showing the gorgeous lifestyles of celebrities and the super-rich, but it has no bearing on many people’s lives. Perhaps it is precisely because the economic disparity is much worse today that the modest living spaces of Tokyo 30 years ago seem so charming.”

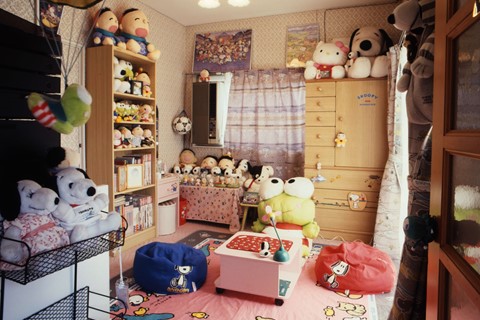

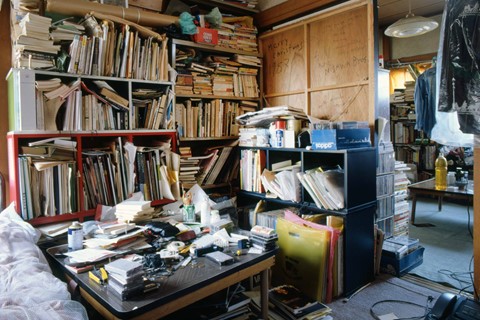

Across 388 pages, Tokyo Style invites the viewer to refocus their lens when it comes to the romanticisation of everyday life in the city. Challenging the picture-perfect minimalism so often sold as archetypal Japanese living, the one hundred or so homes immortalised by Tsuzuki narrate a love story so many living out their fantasies against the backdrop of high-density urbanism will resonate with. From London and New York, to Shanghai and Mexico City, anyone who has moved to these cultural centres will recognise pieces of themselves in these portraits of domesticity.

Keeping true to Tsuzuki’s desire to capture the human condition with candid authenticity, the book’s eight main sections speak to the desires, agendas and leanings of the homes’ inhabitants, articulated via their interior choices. Tokyo’s residential spaces are famously small, and the compact, often overpopulated homes in Tokyo Style do little to dispel this archetype. What is apparent as you journey through the city from page to page, is the myth of minimalism that plagues our misunderstanding of Japanese culture. From record-stacked living rooms to kitchens with more utensils than centimetres of workspace, it’s clear from Tsuzuki’s images that the Western world has much to unlearn about the consumerist habits of its Eastern neighbours.

In his newly-penned introduction to the reissue of the book, writer Yourgrau cites the rise of Marie Kondo as his unlikely route to the photographer’s seminal work. He explains, “My memoir about clutter, hoarding, and collecting, Mess, came out in 2015. A few months prior, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up had appeared in English and proceeded to engulf the planet, so it seemed, with its will to decluttering and minimalism under the marketing halo of ‘Japanese style’. I’d become pro-clutter ... I started writing an article on the Kondo phenomenon, and a friend in Tokyo told me about Tokyo Style. I wrote to Kyoichi right away from New York, and we immediately found a kinship.”

As mentioned by Yourgrau, Tokyo Style was published in the earliest days of the Internet, when only 12% of Japanese households included personal computers. As such, a distinct lack of homogeneity defines this collection of images. In his new afterword, Tsuzuki questions whether the same work could be produced today with the rise of uniformity in habits, experiences and purchases as a result of streaming services, smartphones, fast fashion and food delivery services. He concludes, “The nostalgia that rises in me today when I look back at Tokyo Style is not because of the CRT TVs and stereo sets, but because the rooms used to be the richest expression of the individuality of the residents, the Wunderkammer of each and every one of them.”

Tokyo Style by Kyoichi Tsuzuki is published by Apartamento, and is out now.