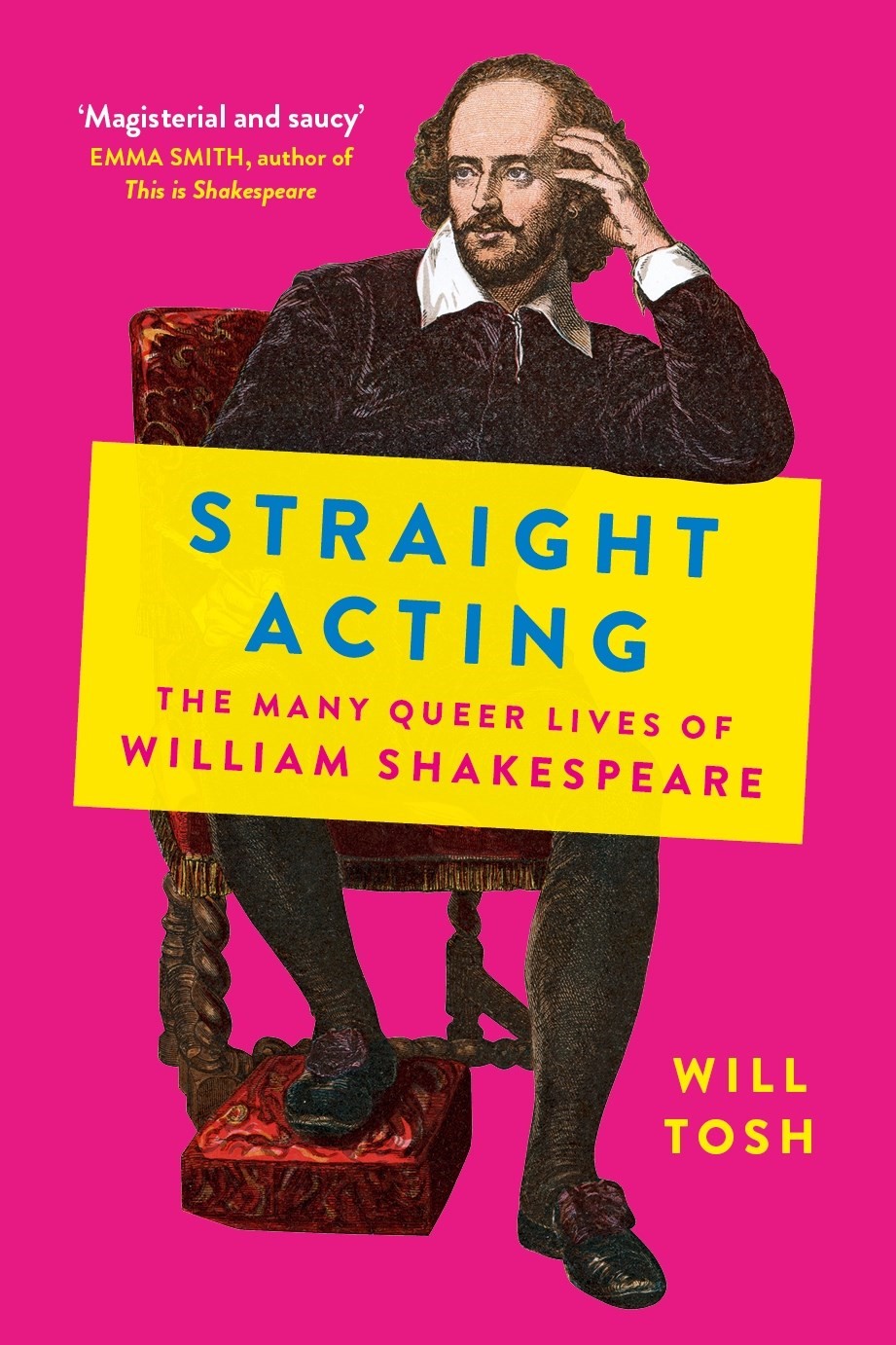

Will Tosh wants us to rethink our national poet. In his tremendously entertaining new book, Straight Acting: The Many Queer Lives of William Shakespeare, he argues that it’s not just the Bard’s sonnets that have “suffered un-gaying”, but also some of his best-known plays. In the opening chapter, he asks rhetorically: “How many of us, reading Shakespeare at school, were given the chance to explore the queer relationships of Sebastian and Antonio (Twelfth Night), Bassanio and Antonio (The Merchant of Venice) or Orlando and ‘Ganymede’ (As You Like It) on their own terms?”

But Straight Acting offers more than a forensic examination of queer and queer-coded moments in Shakespeare’s work – the vast majority of those sonnets were written about a “fair youth” who definitely wasn’t female. It also explores the overlooked queer corners of the supremely patriarchal world that Shakespeare grew up in: from the homoerotic literature he read at school to the arty London suburbs where he and other ambitious young men shared rooms – and beds – to save money. Tosh, whose day job is heading up research at Shakespeare’s Globe in London, steadfastly refuses to label the Bard “gay”, “straight” or otherwise. Instead, he paints a fascinating portrait of an artist who experienced queer desire in a world that allowed it – provided you had the right education and class background.

Speaking from his office at the Globe, Tosh says our conception of Shakespeare can tell us a lot about how we view ourselves as a society. “Because Shakespeare’s been so central to our education system and cultural life, he’s incredibly powerful – that’s why different approaches to Shakespeare can cause frustration and anger,” he says, acknowledging that some people may not be ready for the systemic “un-gaying” to end. “People recognise the value of Shakespeare and the potency with which he can articulate our own feelings about ourselves, so he’s a real touchstone in terms of modern identity.”

Part playful polemic, part queer social history, Straight Acting is a book that casts The Bard’s enduring brilliance in a surprising new light. Here, Will Tosh discusses some of its key themes.

Nick Levine: What made you want to explore Shakespeare’s queerness in such a witty, accessible way?

Will Tosh: For me, reading Shakespeare was always quite a queer experience. I strongly remember feeling a sense of welcome recognition when I read Twelfth Night as a gay teenager – I wasn’t wildly thrown or disturbed by it; it sort of helped me to understand my own queer identity. But then, later when I became an academic, I was a bit surprised that this easy recognition I’d experienced when I was younger wasn’t really reflected in any books about Shakespeare that I read.

When the topic was raised [in these books], it was done in a fairly binary and unimaginative way: “Was Shakespeare gay or wasn’t he? What proof can we offer to categorise Shakespeare, almost regretfully, as a historical homosexual?” And I thought that seemed to be entirely missing the point. I saw no point in wasting time on a historical cold case when what we find in his plays is something more capacious and exciting, which is a real recognition of queer desire as something that sits inside humans.

“Even I was surprised to find this institutionalisation of queer desire so visible in Shakespeare’s culture and in his own work” – Will Tosh

NL: Was part of your objective to humanise Shakespeare in a way? Because he’s such a cultural monolith, it’s easy to forget he was a real, breathing, flawed person.

WT: I think that’s a really good way of putting it. I’m really struck by this idea of Shakespeare as a universal genius who speaks to everyone, which has come in for a really appropriate challenge in recent years as we realise that not everyone looks and feels like an Englishman from the 1600s. You know, one of the reasons we celebrate Shakespeare is because he gave us an extraordinary body of art that speaks to human experiences plural. But it’s also a body of work that so many subsequent generations of writers, thinkers, philosophers and lawmakers have built on to remake the world in its image.

But at the same time, there are other themes in Shakespeare’s work that the same people who celebrate his universality tend to dismiss as being historically contingent. The expressions of queer desire tend to get sidelined in this way, as do the ways he speaks about racial identity and class.

NL: Why do you think the queerness in his work has been sidelined for so long?

WT: Oh, because of psychopathic cultural homophobia. The notion that a celebrated dead white literary Englishman might not have been 100 per cent straight wasn’t a conversation that our educational and cultural gatekeepers wanted to have until very recently. And I suppose that’s part of the bigger history of the way in which sexual desire has been crystallised into sexual identity categories. From the 18th century on, there was a real kind of holy horror at the idea of queer desire and sodomy. Interestingly, this horror wasn’t as present in Shakespeare’s time, though Shakespeare’s time was certainly no queer utopia.

In a funny way, the emergence of this horror of queerness, particularly male queerness, came at the same time as the development of Shakespeare as a national icon both at home and abroad. Shakespeare was marketed around the world as a symbol of imperial Englishness, and nobody wanted to drop queerness into that equation.

“I’d love for people to come away with a sense that our understanding of Shakespeare isn’t final. It will continue to evolve as we evolve, and that’s entirely healthy” – Will Tosh

NL: Did anything about Shakespeare’s queerness surprise you when you were researching this book?

WT: For me, it was the discovery that Shakespeare was a published poet at a time when there was this marketing and packaging of a form of quasi-pornographic queer literature to an eager, mostly male readership. Even I was surprised to find this institutionalisation of queer desire so visible in Shakespeare’s culture and in his own work. I’m thinking partly about his sonnets, but also about his gorgeous long poem, Venus and Adonis, which isn’t as widely read [today] as his plays.

NL: Finally, what do you hope people take away from the book?

WT: I would love readers to feel that they weren’t told everything about Shakespeare in school. It’s a good thing to realise that the way we talk about celebrated people from history is itself really time and history-bound. We talk about these people in ways that reflect our own society’s concerns. So we might think that Shakespeare is a kind of an unchanging monolith, but he isn’t. He’s been reinterpreted countless times over the past four centuries: that’s how history works, how literary criticism works, and how we understand our culture. So I’d love for people to come away with a sense that our understanding of Shakespeare isn’t final. It will continue to evolve as we evolve, and that’s entirely healthy.

Straight Acting: The Many Queer Lives of William Shakespeare by Will Tosh is published by Sphere, and is out now.