This story is taken from Scenery Number Two, which is out now:

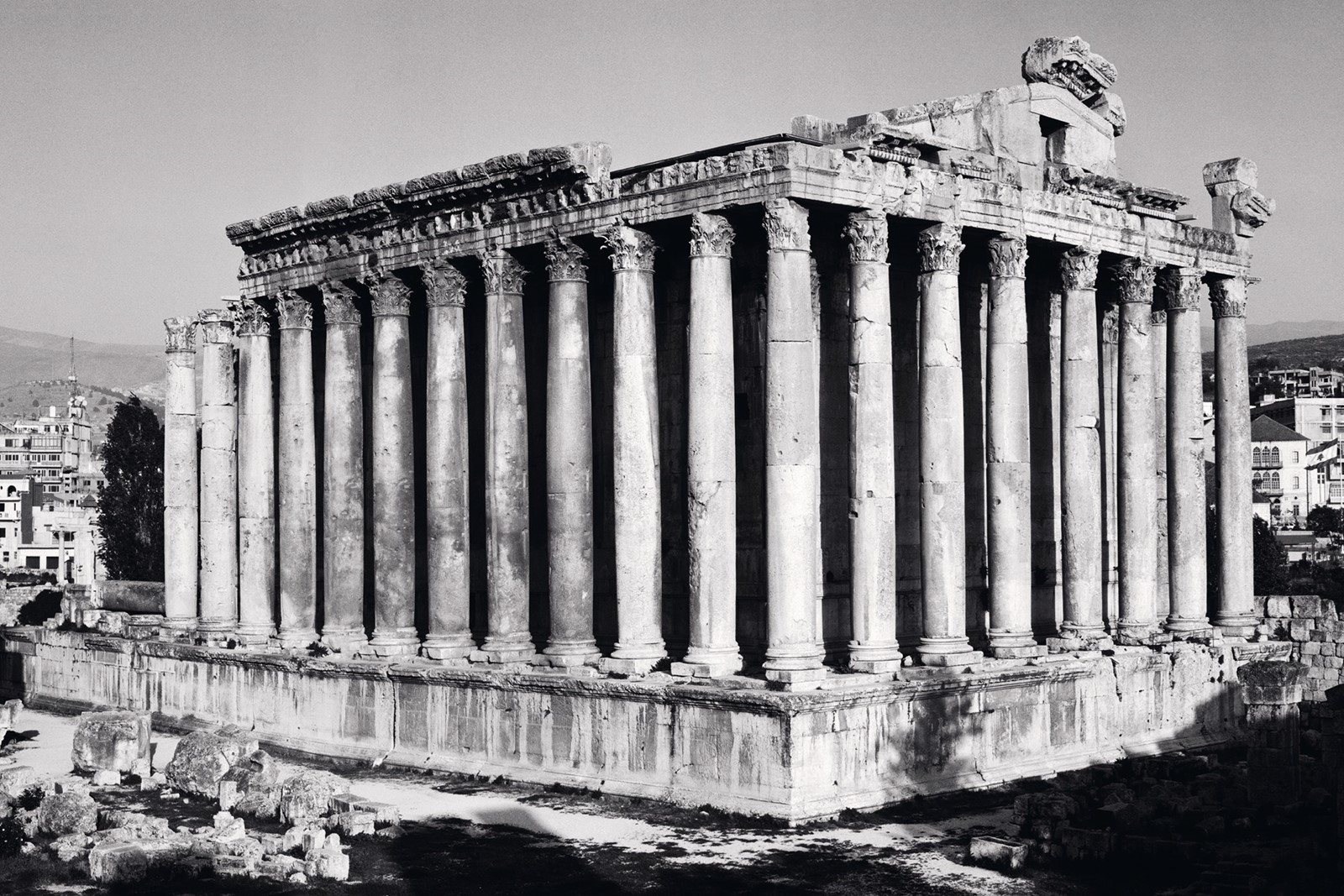

The location of Palmyra, nestled in the heart of the city of Baalbek, has been both its biggest blessing and its greatest curse. Since the war that sparked in 1975, Baalbek has been completely neglected by the state and left in the hands of Hezbollah (a pro-Iranian militia) and other family tribes who, at the slightest provocation and until this day, exchange gunfire. Like a family jewel, the Palmyra was buried amid this chaos. Today, and more than ever before, it seems to emerge from the ruins of what was once called Heliopolis, the City of the Sun. Throughout the day, the silhouettes of the Temple of Bacchus (one of the grandest and best-preserved Roman temples in the world) and the Temple of Jupiter (the largest monument dedicated to the deity in the history of the Roman Empire) appear to be drawn on the façades of the Palmyra. And this sight alone is poetry. At sunset, the hotel has something almost biblical about it. On the terrace, the colours are weaved together by gold. It’s here that the poet Jean Cocteau wrote: “The mysterious terraces of Baalbek, from which it is assumed that men embarked towards the stars, are they not the ideal place for the soul of poets to take flight and set sail?” Seeing, from this spot, the columns of the Temple of Bacchus drawing their boundaries with the sky, one suddenly forgets that outside this isle, the country is so damaged.

In effect, the precarious situation in Lebanon since Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, has dealt a significant blow to the establishment. Today, Palmyra is a place that is both deserted by its past and very much inhabited by its memory. It’s a national treasure whose secrets are kept within an imposing guest book at reception. As visitors flip through its pages or walk down a long corridor leading to the derelict dining hall, they seem to encounter spectres of historical figures who once resided in one of the 25 guest rooms. Such company includes German emperor Wilhelm II, Charles de Gaulle, François Georges-Picot, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Albert Einstein, and even some legendary artists who graced the stage of the Baalbek festival – notably Joan Baez, Ella Fitzgerald, Herbie Hancock, Fairuz, and Fanny Ardant.

Rima el-Husseini holds a special memory for Nina Simone: “It was in 1998, we had to carry her on a chair to her room in the annexe,” she recalls. “I will never forget that magical encounter, like all the others that make up the story of Palmyra. She asked for a bottle of Veuve Clicquot rosé before going on stage, and we had to scout the entire Beqaa Valley to find this for her.” Likewise, climbing the creaking wooden stairs, it’s impossible not to see the poignant mark left by Cocteau after his two stays at the Palmyra in 1956 and 1960. Just push open the door of Room 27 to discover his sketch of a face with troubled, haunting eyes blown onto a wall like stardust. “Like every visitor, this character seems to look at the temples of Baalbek through Palmyra’s eyes. That, in a few words, is the experience our establishment offers,” muses Rima, who managed the hotel from 2010 until her son Hassan recently took over.

What I remember most from my last visit to the Palmyra is the impression that here, everything seems to resist time. The concierge Ali is a character from another era, with his slow and outdated elegance. The cats that come to lounge on the ancient sculptures scattered in the lobby and bar, both untouched, feel frozen in another time. The intact furniture like sentinels of the past. The lace curtains, and the sheer mosquito nets above the beds, billowing in the wind.

The old shutters weathered by time and sun. “Conserving this spirit was a battle in its own right,” confirms Rima. A battle indeed: like facing the repeated comments of those who, upon arriving at the hotel, seek out the minibar, air conditioning, and other hyper-comforts customary in today’s holiday palaces, oblivious to the fact that Palmyra’s notion of luxury lies elsewhere. It’s in the magic that operates in every nook of this place; where a fragment of the country’s history is also sealed, as the signing of the Grand Lebanon Declaration in 1920 took place here. “I’ve always received many comments like this or that needs refurbishing, this or that needs changing, this or that needs modernising. But the more time passed, the more determined I felt to do the opposite, which is to preserve this place as it is. Because Palmyra is exactly that: a time capsule,” insists Rima. Furthermore, “the problem is that the region has always been associated with conflicts, fuelling a certain fear among the public who came to attend concerts at the Baalbek festival but hurried back to Beirut,” she says. The silence that weaves through the daily life of Palmyra today is not unusual. “It might seem strange, but we’ve experienced for years what the country is going through now,” she adds. “It only takes an incident in the region for the hotel to empty out. [But] this crisis seems to us like one too many.”

So, witnessing Palmyra survive all of this – especially the past eight months during which the region, under Hezbollah control, has been regularly targeted by Israeli airstrikes – is nothing short of miraculous. Its mere existence feels like a promise to safeguard a Lebanon that is slowly disappearing.

Scenery Number Two is out now.