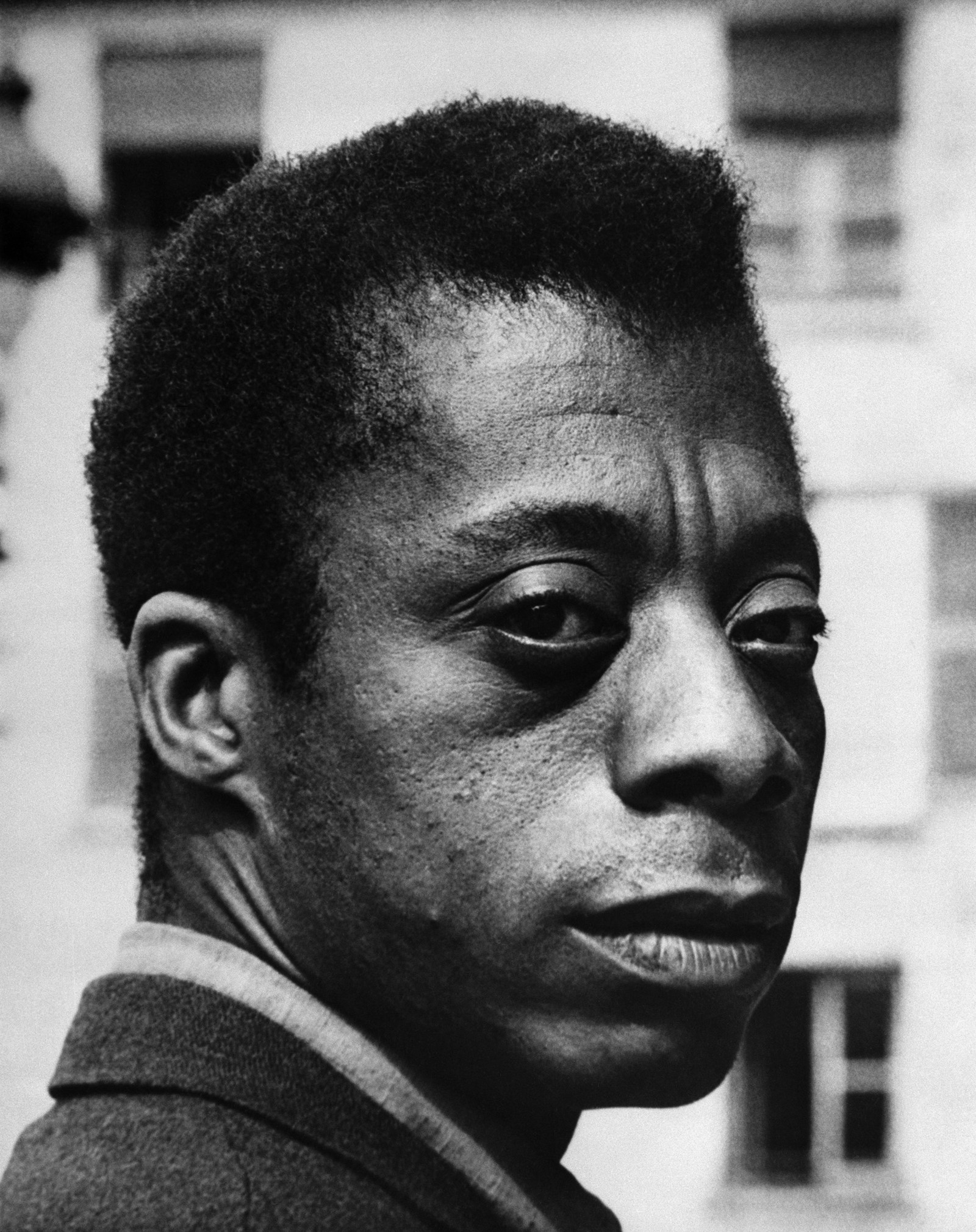

Among the great American writers of the 20th century, James Baldwin stood as a singular force on the global stage during the height of the Civil Rights Movement and Gay Liberation. Fearlessly speaking truth to power, Baldwin transformed the page into a stage that held readers spellbound in his rapturous prose on taboo subjects like race, sexuality, masculinity, and class.

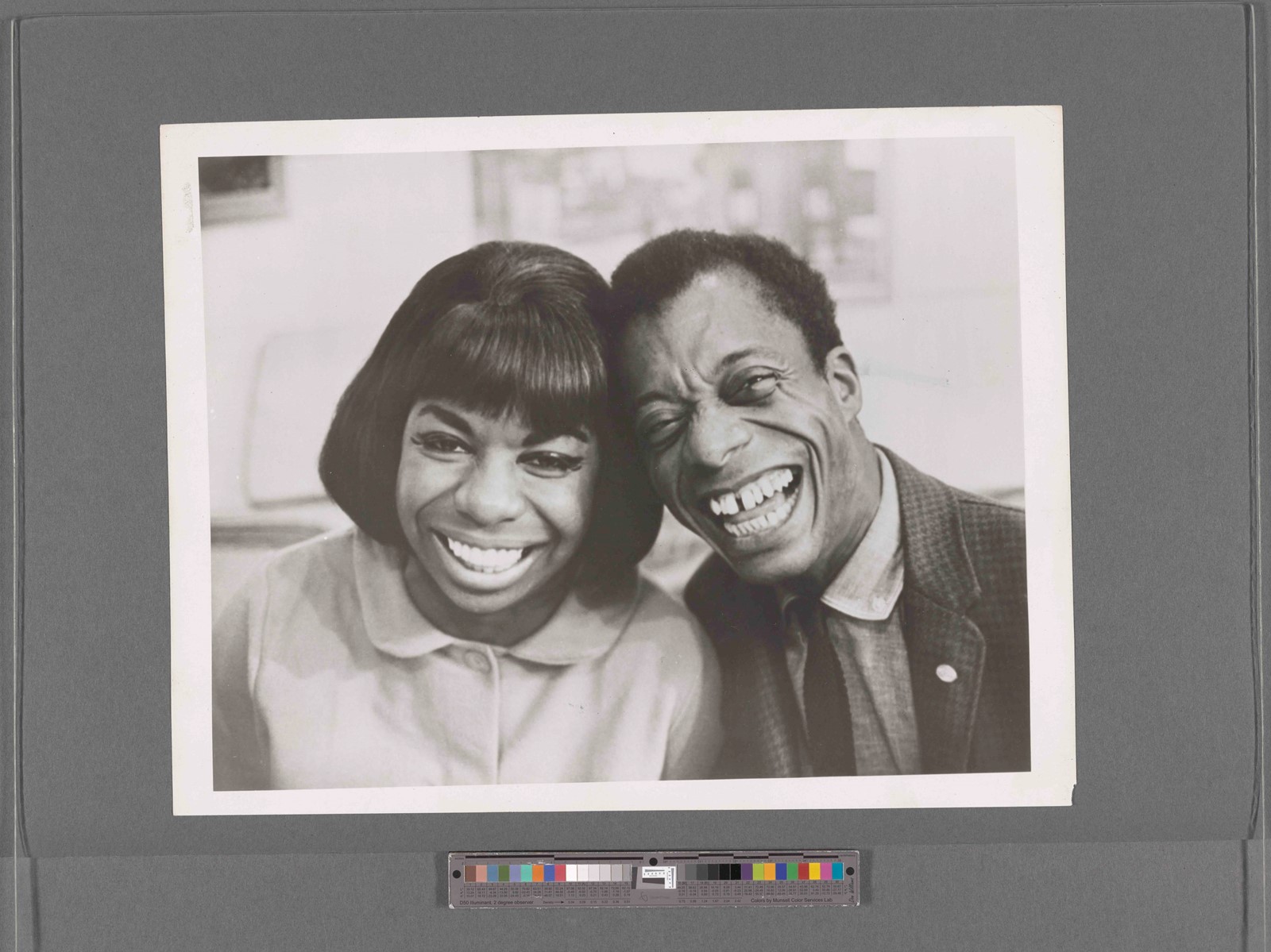

In celebration of the 100th anniversary of Baldwin’s birth on August 2, his life and legacy is once again brought to centre stage. The new exhibition and catalogue, This Morning, This Evening, So Soon: James Baldwin and the Voices of Queer Resistance at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC, explores the interwoven lives of Baldwin and his inner circle of artists, activists, musicians and writers, including Lorraine Hansberry, Bayard Rustin, Essex Hemphill and Nina Simone.

The show draws inspiration from the 2019 exhibition God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin, curated by Hilton Als and published for the first time earlier this year. “It was marvellous to bring back Baldwin’s body, his voice, his spirit, and all those aspects in the curatorial work; that was the joy,” Als says. “The difficulty was, how do we get past the ideology and the image of this person? How do we honour him?”

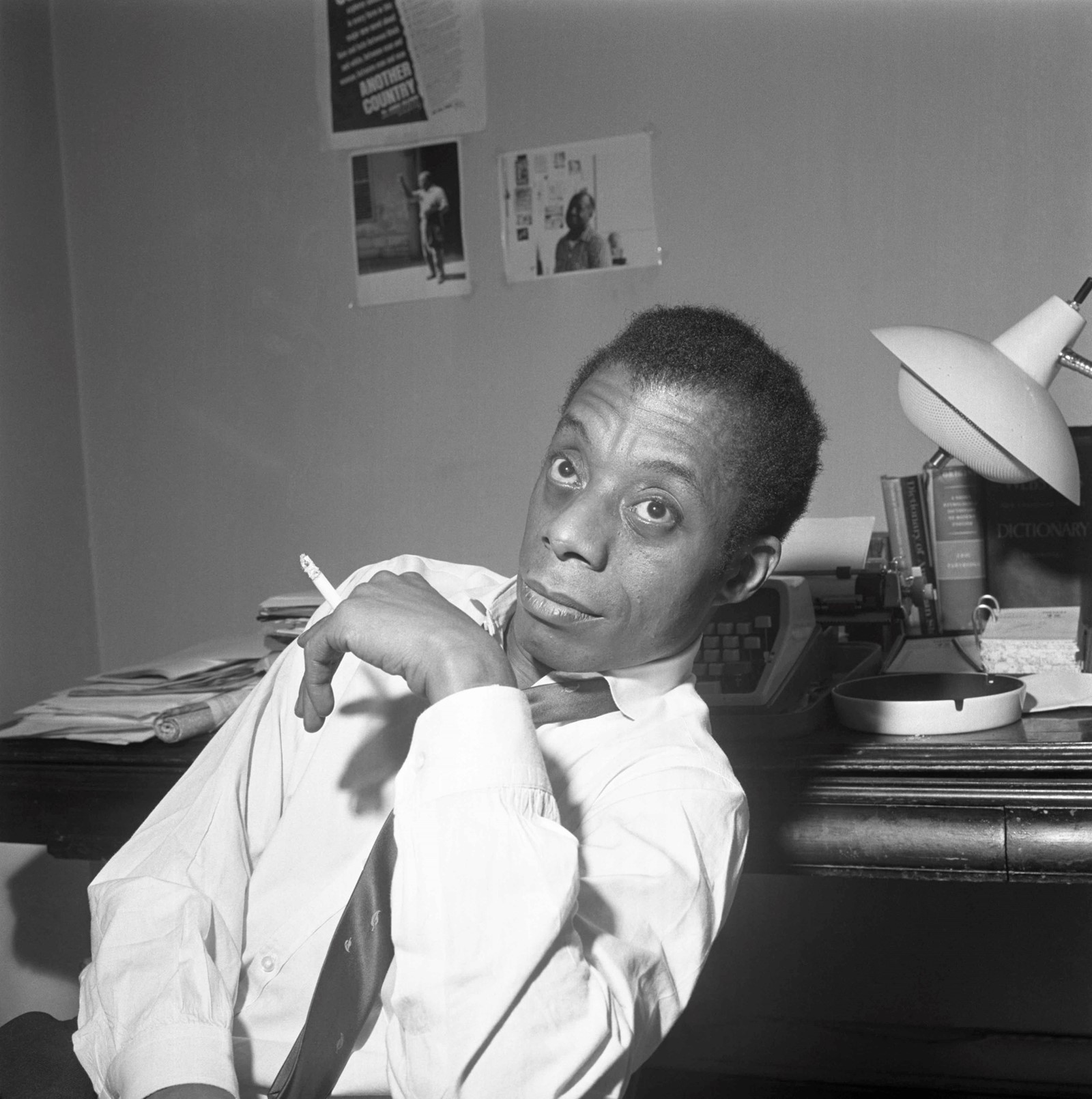

It is a question that contains multitudes, like Baldwin himself. The new exhibition, JIMMY! God's Black Revolutionary Mouth at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York, presents selections from the James Baldwin Papers alongside photographs by Steve Schapiro from their seminal 1963 collaboration for Life. Holding a mirror to the world, Baldwin began the essay with an intimate, collective truth: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.”

Here, four writers, photographers and filmmakers – Hilton Als, Shawn Walker, Maura Smith, and Anthony Barboza – speak on Baldwin’s artistic legacy.

Hilton Als, Writer, Curator, and Author of God Made My Face

“[Reading James Baldwin’s work] alerted me not only to the power of words, but to the power of freedom. I felt that what Baldwin was doing, particularly when I was a kid reading Notes of a Native Son for the first time, was incredibly brave in terms of the Black domestic life as I knew it; you never really told stories outside of the family.

“It took me many years to understand the only thing he had was his voice. He didn’t have any money. He didn’t have any prospects of success. He didn’t have heterosexuality. But what he did have was this voice, and if you could put your voice first, the rest took care of itself. If you have this voice, you had an incredible tool: the articulation of your soul, and what your experience has been. Understanding that the voice had no obligation other than to realise itself was a big release for me.

“Baldwin was a prodigy and he was very clear early on about the moral responsibility of his writing and what he was going to have to do to honour that voice, whether it was emigrate to Paris or not live in Harlem. He gave himself an education; he gave himself space to create. Even before I could absorb the other stuff, I was impressed by [the life he created for himself] first; and then I began to understand the moral imperative of taking care of your voice.”

Read our interview with Hilton Als on James Baldwin here.

“If you have this voice, you had an incredible tool: the articulation of your soul, and what your experience has been” – Hilton Als

Shawn Walker, Photographer and Founding Member of Kamoinge, Archive in the Library of Congress

“I read Giovanni’s Room in the early 60s. My brother never spoke about being gay, and I was trying to say, ‘Hey man, we should be able to talk about this’. I didn’t read any other books because I was focused on photography, so I followed Baldwin in the news. I read anything published about him and watched his interviews. I always wanted to know what he as saying. He was one of the most outspoken writers at that time. He was gay, and he was respected. You have to remember, those were terrible times for the gay people and what he had to say was so important that people had to listen. That within itself gives you strength.

“James Baldwin gave me a sense that I had the ability to become a creative person because he came out of the community and wrote these powerful books that the world recognised. I remember when [photographer] Roy DeCarava came to the [Kamoinge] group; he looked at our photographs, and said, ‘You guys are trying to be artists.’ I didn’t realise that on my own. I was just starting to learn, and thought it was photography or jail – or physical labour, and I didn’t want to do that either. I didn’t know what I wanted to do but I knew there were talented Black people out there that the world was recognising. So I knew I could do this. I’ve lived my dream.”

Maura Smith, Filmmaker, and Wife of Photographer Steve Schapiro

“Steve [Schapiro] was a literature major. He was one of the first Jews to attend Amherst College, but he thought it was too structured so he transferred to Bard. He went to Paris in 1954 to be a novelist and he was very proud to tell you that the first five pages of his novel were excellent.

“In 1963, Steve read James Baldwin’s essay The Fire Next Time in The New Yorker, went to his editor at Life, and suggested a photo essay. The editor connected him to Baldwin’s people, and they travelled from New York to the American South. Steve said that Baldwin always did everything in disaster mode; they would always be the last people on the plane. He was wonderful and incredibly intense. One of Steve’s favourite photos is the picture of Baldwin holding up the album cover that says ‘Do you love me?’ He had a real loneliness about him.

“Steve mentioned [that] his literature degree really helped him in conversations because it had nothing to do with photography. I could easily see them hitting it off in terms of their love of literature and France. Steve always cared about politics and Baldwin introduced him to people in the Civil Rights Movement. It opened him to this path he would travel for the rest of his life.”

[On meeting James Baldwin] “It’s a feeling that goes all through your body. It’s a spiritual thing, like an aura” – Anthony Barboza

Anthony Barboza, Photographer, Founding Member of Kamoinge, and Author of Eye Dreaming

“I came to New York in 1963 when I was 19 because I wanted to go to this photography school. I had an aunt who knew Adger Cowans, and he took me to a Kamoinge meeting. They mentioned James Baldwin. I didn’t know who he was, so I got a book, Another Country.

“While I was working on the Black Borders series in 1975, I met a model who said, ‘I see you don’t have James Baldwin there. If you photograph me, I will get Baldwin’. So I did that, and when the time came, Baldwin showed up with an entourage of about seven people. They never said a word. As I prepared myself to photograph Baldwin, I experienced something I’ve only felt slightly with Cesar Chavez and Alice Walker. It’s a feeling that goes all through your body. It’s a spiritual thing, like an aura. When a person gives their whole life to help others, it is unbelievable.

“When you read Baldwin, you can almost write the word that’s going to come next; the flow of his literature is really something. I’ve read a lot of his work through the years, and he definitely affected me. It’s about doing the work to honour the ones who came before me. I think that comes from reading Baldwin at a young age. It’s always been about that.”

This Morning, This Evening, So Soon: James Baldwin and the Voices of Queer Resistance is on show at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC until 20 April 2025. The catalogue will be published by Delmonico Books/National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution on 27 September 2025. JIMMY! God's Black Revolutionary Mouth is on show at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York until 28 February 2025.