There’s something about summer that always brings back the feeling of being a teenager. For the fourth season of Girlhood Studies, Claire Marie Healy examines the close relationship between girlhood and the summertime: as we experience it in our lives, and re-experience it through visual culture. This edition will publish weekly, with one for every week of the school holidays.

In the summer of 1952, when she was 19, Sylvia Plath journalled – not for the first time – about the melancholy of summer rain. “Three years ago, the hot, sticky August rain fell big and wet as I sat listlessly on my porch at home, crying over the way summer would not come again – never the same,” she writes of an earlier teenage romance, adding, “August rain: the best of the summer gone, and the new fall not yet born. The odd uneven time.”

There really is something uneven – and uneasy – about August. Hot, swollen and seemingly without end, it’s a time of year, as Plath identifies, that feels like waiting. And, much like prom night or your wedding, it’s precisely because the summer is meant to be a time where everybody enjoys themselves that it can warp under the weight of pressure. Writer Paula Mejía, in a recent Dirt piece I enjoyed, even goes so far as to explore the concept of reverse seasonal affective disorder, with potential summer symptoms including “insomnia, mania, and a zapped appetite.” And as the seasons for all the girlhoods to come get literally hotter year-on-year, the summertime SAD-ness doesn’t look to be going anywhere.

Disorienting, blinding and overlong: the conditions of the summer are designed for things to get a little weird. Soon enough, our feeds will be filled with the usual odes to the onset of spooky season (I expect all girlhood scholars to observe the usual traditions of posting images of Rory Gilmore, Jena Malone and Jake Gyllenhaal in a skeleton suit, and that photograph of Chloë Sevigny with a rifle and a pumpkin). For now, I find myself wanting to see out August by watching those films that make the case for the summer as girlhood’s real spooky season.

The most effective horror stories hover somewhere between fantasy and reality: the kind of terror that forms in the spaces where we doubt what we have seen. One reason a long hot summer provides the perfect atmosphere for strange and unusual things to happen to girls, is that such narratives usually hinge on whether they have made everything up.

Watching Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures (1994), the main thing that struck me was the soundscape of the girls’ sheer noise: it’s impossible to tell, throughout, if the girls are screaming in terror, laughing in glee, or both. The film is ostensibly a true-crime narrative, but it is also a story about the dangers of entering a fantasy world at the expense of lived reality. Centering on teenagers Pauline Parker (Melanie Lynskey) and Juliet Hulme (Kate Winslet) and their obsessive, hurricane best friendship, it details the period leading up to the girls’ murder of Parker’s mother as revenge for her not letting them run away together to Hollywood. But it’s also a strangely apt precursor to Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, with the visual landscape of the film swerving between conservative, dull 1950s Christchurch, New Zealand, and the verdant, technicolour, The Wizard of Oz-esque “fourth world” that the girls believe they can access with their minds. The film is all the more eerie for the intense detachment the girls, in their love of nothing else but one another, feel from the world and the people around them. The fact that Heavenly Creatures’ events take place in the context of family trips to the beach or countryside walks, with the girls in their matching girlish floral dresses, makes the horrific events all the more shocking in relief. It’s a sense of spooky dissonance bolstered by the film’s voiceover, which is based on the diaries of the 14-year-old Parker that the police found. “Our main idea for the day was to murder mother. This notion was not unusual but this time it was a definite plan which we intend to carry out,” in terrifying deadpan.

Far more innocent – and surely the first Walt Disney movie I have ever recommended in this column – is The Watcher in the Woods (1980), a film that, from cursory glances online, seems to have scarred many an 80s childhood. In the live-action film, a teenage girl – all California sunshine with her perfect bangs and satin bomber jacket – moves to a clearly haunted house in the rural English countryside with her family, owned by (an incredible) Bette Davis. Over the course of the summer, she learns of the old woman’s lookalike teenage daughter who disappeared mysteriously during a solar eclipse 30 years earlier. Disney has since disowned the film, but it’s an impressive example of the spooky girlhood genre: much like Japanese classic Hausu (1977) or even Sofia Coppola’s The Beguiled (2017), the boredom of a long summer spent in an isolated haunted house allows otherness to creep in.

The throughline with many of these films is that the teenage girls are the only ones who can see the supernatural – their position between childhood and adulthood is what allows them to channel other kinds of in-betweenness, like spirits who haven’t quite left this world into the next. But rather than hinging entirely on what the girls believe they saw, the genius of Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) is how it loses sight of the girls altogether.

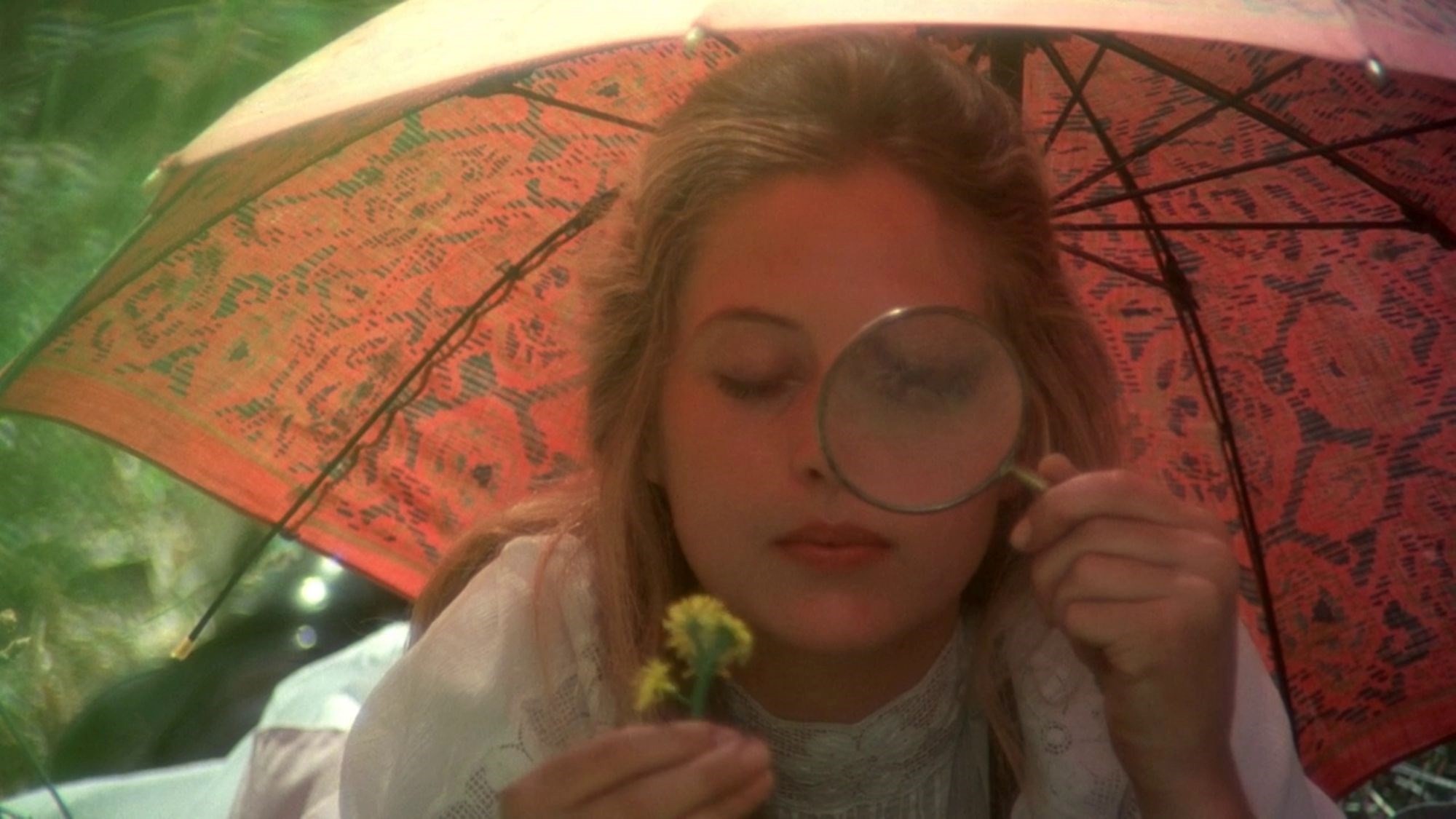

Based on the 1967 novel by Joan Lindsay, the film is set at the turn of the 20th century and concerns a small group of students from an all-girls college who vanish, along with their chaperone, while on a St Valentine’s Day outing to a local sight. The reason the film is a genuinely disquieting experience – other than the fact that its central mystery of what happened to the girls is never seen by the viewer, or resolved for the other characters – is that it all unfolds not only in “broad daylight”, but in a daylight so broad that it blinds us.

In their beautiful muslin white dresses and straw hats, the girls – especially the most beautiful and mysterious, Miranda – are shot in such a way that they seem to glow against the face of the rock they explore, like they are themselves charged with light. Something that struck me, this time, was that part of the film’s horror lies in the structures of “standards” of obedient girlhood: the fact of their school mistress putting them into black stockings, corsets and pretty white dresses in the first place to explore this dangerous terrain in the height of the Australian summer. The film’s producer, Patricia Lovell, has spoken about this, saying in 1993, “This is why there are so many problems now (in Australia) because no lessons were learned from the original people … They just decided to do all of this on European standards. It’s just so crazy and so desperate. To me, it wasn’t a romantic story, it was a horror story.” Such enforced contradictions are era-specific to 1900, of course, but much of the ideology of what girls ‘ought’ to look, act, and be like persists. (The film’s subtitle is emphatically one of the horror genre, too: “A Recollection of Evil”).

This column has sometimes spoken about the impact of Alice in Wonderland as a children’s book character that, in its visual expression in culture, became an adolescent girl – producing many offshoots in terms of how we understand girlhood. When watching movies of girls in spooky summer scenarios, I kept thinking of another turn-of-the-century girl – two sisters, actually: Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, who, aged 16 and nine respectively, took photographs as evidence of the fairies at the bottom of their Yorkshire garden. Of course, rather than the Saviours of the Theosophical movement and conjurers of magic they were initially heralded as, the two girls behind the Cottingley Fairies were simply bored girls in the summer. But they were also artists.

And even when the jig was up, and confessions made – one of the sisters, as an old woman, kept insisting on the fifth and final image’s reality. I often think about that.