Neo Sora draws on his own turn to activism in his sci-fi teen drama, a highlight of this year’s Venice Film Festival

In Happyend, Neo Sora serves up a startling visual metaphor for the wayward creativity of youth. Breaking into their school’s music room one night for a party, BFFs Kou (Yukito Hidaka) and Yuta (Hayato Kurihara) spy a forklift truck in the car park, right next to their headteacher’s brand-new sportscar. Cut to class the next morning, and kids and staff alike look on in amazement at the car, now turned perfectly on its end outside. “It’s so artistic!” says one pupil admiringly, before the upturned vehicle is fenced off like a prized sculpture in a museum.

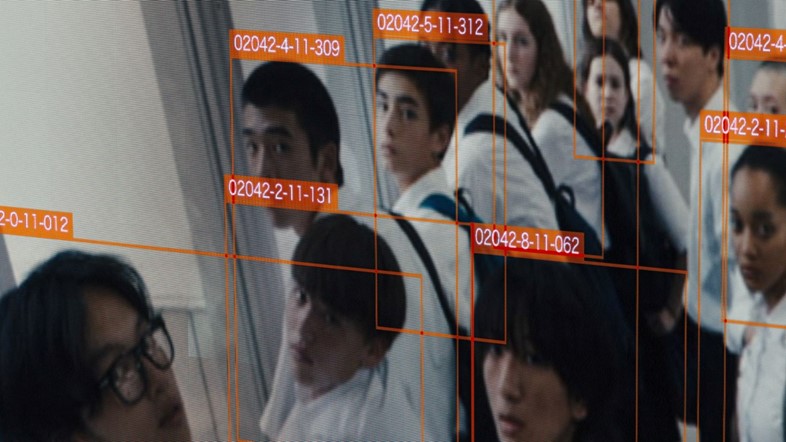

It's a moment of comedy in a film which attempts an implausible balancing act of its own. A high-school drama with a sci-fi twist, Happyend turns on the bromance of Kou and Yuta, two techno-loving misfits whose friendship falters when an earthquake hits, prompting their school to bring in a surveillance-camera system for the pupils’ ‘safety’. Kou, a second-gen Korean migrant used to being branded a troublemaker, joins a gathering protest that puts him at odds with Yuta, whose apolitical nature he comes to resent. Inspired by Sora’s own turn to activism in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, it’s a film about teens torn between the impulse to party and to act meaningfully in a world that feels, in some deep and inexpressible sense, like it’s “already over”.

“Today young people are confronted with these extremely large-scale political and social issues that feel totally out of their control, and yet they’re the ones that are going to have to deal with it the most,” says the 33-year-old director, who admits he cut himself off from friends who were out of step with his views during this period. “If you lived in relative privilege in the past you maybe didn’t have to engage, but at this point it’s something you’re forced to participate in. You can feel it every day, especially with global warming and environmental disaster and constant images of genocide and war around the world. So I think it’s always going to be present for a lot of people, especially through the phone.”

Sora’s fiction-feature debut unfolds in a Tokyo of the near future, nudged a few steps closer to the kind of techno-fascist society he sees in incipient form today. It’s the film he’d planned to make before refocusing his energies on Opus, a poignant concert film featuring his dad, Yellow Magic Orchestra musician and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto, before his death from cancer in 2023. A US native who grew up between Tokyo and New York City, Sora borrows documentarian Kazuhiro Soda’s phrase “dispassionate fascism” to describe Japan’s rightward creep under prime minister Fumio Kishida, which “has a different flavour from some other European instances… It’s more about this slow, quiet sense of fascism that presents itself as really boring. And because of that, no one’s paying attention; they just go ahead and do whatever they want.”

In fact, the “emergency decree” declared in the film is a direct rip from today’s headlines, Kishida attempting to drive through constitutional reforms that would hand unprecedented power to the executive. But the real-life events that drove Sora to make his film unfolded much earlier, with the earthquake of 1923 that sparked a massacre in Japan, after racist conspiracy-mongering brought populist rage down on the country’s Korean community. “They killed something like 6,000 people in the span of two days,” says Sora. “For me it was a big shock [reading about it]; I really wanted to understand how something like this could happen. And the more I learned about it, the more I started to think about [parallels with] today, because there were all these horrible hate-speech protests against Koreans going on at the time. They say in Japan within the next few decades there will be a big earthquake like the one a hundred years ago. And so I was like, if we don't do something about this trend I see happening now, another massacre could happen.”

None of which makes it into Sora’s finished script: Happyend is not that kind of film. Instead, it’s a heartfelt drama which, in bouncing between moments of comedy and mounting anger, seeks to understand the diverging paths its two best friends take – and perhaps to mend a few burned bridges of Sora’s own. “I don't really believe that a film needs to be a comedy to have a little bit of humour in it,” he reflects. “Every day I find a lot of humour in the way I see things. But then in another moment, I’ll be just, like, furiously angry about something. And so I think my personality really helped shape the tonality of the film. Because that’s just how I am.”