Torrey Peters is thinking about legacies of autocracy across the Americas and how writers have survived right-wing governments through periods of exile. She’s been living part-time in Colombia, watching events unfold in her native US and considering the interconnecting histories of people, goods, and ideas across the continents – “and it’s much closer than I was trained to believe as a midwestern American.”

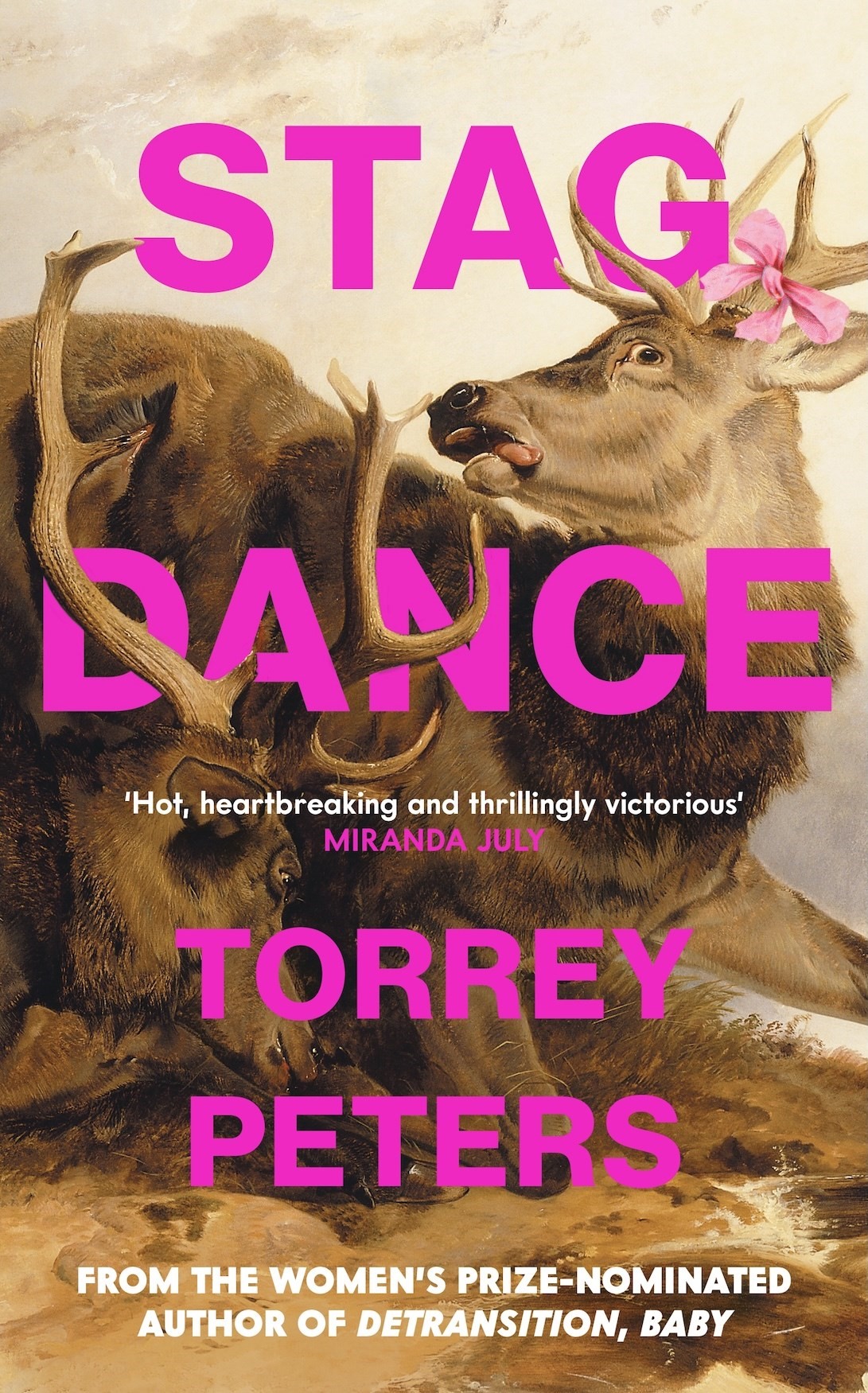

The bestselling author of acclaimed 2021 novel Detransition, Baby is about to publish a collection of stories exploring transness across time periods and genres, from an apocalyptic future to a Quaker boarding school ripe with adolescent longing to a nightmarish weekend in Las Vegas. The longest story is the titular Stag Dance, set a century or so ago on a logging camp among lumberjacks menaced by cold, loneliness, and a mythical creature known as the “agropelter.” Its narrator is an axeman nicknamed the Babe, who decides to attend a winter dance as a woman, his incipient yearnings allowed to flourish through the symbolic pinning of a cloth triangle to the fly. As immersive and captivating as Detransition, Baby, in prose reminiscent of Melville and Twain, Peters conjures an epiphanic winter’s night bacchanal in a brutal landscape. Here, she discusses the erasure of trans histories from the cultural imagination, the complex nature of sisterhood, and the importance of sharing her platform.

Laura Allsop: Stag Dance is so compelling, with this really rich sense of a past that’s very past, and at the same time, feels almost placeless.

Torrey Peters: It started out very specifically in 1915, and slowly I began to like the idea of a tall tale that isn’t the ways that they existed – less in historical fact than a place of imagined Americana. There’s mention of stuff that you could place historically but at some point I became more interested in the invented narrative consciousness of Americana, which I think has had transness erased from it.

The thing about the triangle – that’s historically accurate, it’s from a book called Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past, about gender relations and same-sex relations on the frontier. I wanted to recreate a consciousness in that space, the consciousness of the Babe. I learned that at these logging camps, they would have these dances, and the men would either tie a marker on their arms and literally wear a burlap bag as a skirt, or they would do this triangle thing. I was like, if that’s what they were doing, if these are the facts that history has given me, why would I not run with this totally rich, just ridiculous, and to me, very human thing they were doing?

LA: Is the agropelter something that came from your research?

TP: The agropelter is an unclear kind of cryptid that would kill loggers. It’s not a word that I made up, but I kind of gave it a queer spin. One of the things I was trying to do in that story, which I think is a little bit politically uncomfortable, was I wanted to ask questions about who gets to transition. A lot of this story, for me, was about symbols. We think of transition now as taking oestrogen and growing your hair, but that’s as arbitrary as any other series of things, it’s a series of symbols. I was like, well, what if you stripped down the symbols to the most basic parts, which it turns out, in history, already exists? Just a crude triangle at the crotch and said, “This is transition” – how come it works for this [person]? It seems like I could talk about this through a lumberjack world in a way that is actually more painful to talk about now. Why does this person’s transition seem to be easier than that person’s? Maybe it’s money, maybe it’s the body you’re born with. Maybe it’s all these different things that are actually highly unfair, and yet we have to create solidarity and not live in resentment.

“We think of transition now as taking oestrogen and growing your hair, but that’s as arbitrary as any other series of things, it’s a series of symbols” – Torrey Peters

LA: I want to ask about the idea of sisterhood, which runs throughout the stories, while motherhood was the more overarching idea in Detransition, Baby.

TP: That’s also kind of like an earlier transition mode – you can’t stay mother to another trans woman for very long, because actually she’s an adult. It might last for two years, but then she becomes something like your sister, maybe just your friend, maybe it’s just your acquaintance. I think that sisterhood is a thing that I feel with other trans women. In all of the classics, like with the March sisters in Little Women, there’s rivalry and love and a sense that there’s a finite amount of resources available to you that have to be shared. That your loyalties should be to each other, but sometimes they’re not and the ways that creates intimacy and also a capacity for cruelty. The surface level thing is, we’re sisters, and that means you’re going to defend each other no matter what. But I think that as a slogan, it’s just on the surface, because when you actually look at sister relationships, in literature and life, they’re often the most fraught, the most dark, the most charged with both recognition and rejection. I think pretending that’s not the case, just because it’s morally difficult, is ignoring a lot of things that structure my relationships with people – not just trans people, but people who are likewise to me in all sorts of different ways.

LA: Were there authors who acted as a kind of map for the genre aspect of the stories, from speculative fiction to horror?

TP: The speculative fiction is [influenced] more by movies than books. It’s actually structured like Pulp Fiction: a timeline flashing back and forth and then a loop around to the beginning. A lot of people were like, “you should really flesh out the world,” but there’s been so many dystopian and post-apocalyptic movies – putting my little spin on it didn’t feel necessary. Here’s the thing I really care about, which is relationships with other trans women and the way that your anger can destroy the world, in ways that are good and bad.

For the boarding school story, I’ve always loved Brideshead Revisited, the homoeroticism of it, the tenderness, the nostalgia and the earnestness of it, from someone who was a satirist. John Knowles’ A Separate Peace – there’s a lot of younger, queer, ostensibly ‘boys’ writing that I think I was drawing on. And then the horror – I don’t watch a lot of horror, but I recognise the way that shame can be horrifying. It seemed like horror and the uncanny was the right vessel for talking about my own shame, especially when I was writing it in 2016 when there was a lot of respectability politics around how one becomes trans.

“I think I had the luxury in 2021 to say I don’t represent [trans women]. I don’t have that luxury now. If I’m given a platform, I have to take it and try to share it as best I can” – Torrey Peters

LA: The climate we’re in is almost the inverse of when Detransition, Baby came out. How does it feel to look back on that time?

TP: When I published Detransition, Baby, there weren’t that many trans books out. One of the reasons I think it got as much attention paid to it is that it was marketed as women’s fiction even though it was about a trans woman. That was uncommon. Now, I think there are 15 books by trans women coming out this spring. It’s a bit weird for me because, on the one hand, Detransition, Baby came out at a sort of high water mark of being able to have rights. I was writing, thinking that it would continue, and almost within a year of Detransition, Baby coming out, the real backlash started, in all sorts of realms. If you’d asked me if this was a high water mark, I’d have said no – there’s literally no other books on the shelf with mine. It’s sort of ironic in that I think you can look back and say it’s worse, but people seized upon [that moment]. Just in the UK in just the last month or two, Nicola Dinan and Shon Faye [have published books].

Things end up creating reversals for me. At the time that Detransition, Baby came out, I was really resistant to having anybody say that I was representing trans women. Because there weren’t enough out there, people thought that I was representative. I actually think I’m a bit of a weirdo – I wrote a lumberjack book! This is not representative of anything but my own interests, and yet I was made to represent, and I disliked it. Now I think I’m much more free to represent because there are so many other people I can share the stage with. The political moment is dire enough that if if I’m given a platform to say, “this is bigotry, this is autocracy, this is authoritarianism, this is hate” – and not just for me, but for immigrants, for Black people, for poor people in general – it’s incumbent upon me to actually say it now. I think I had the luxury in 2021 to say I don’t represent. I don’t have that luxury now. If I’m given a platform, I have to take it and try to share it as best I can.

Stag Dance by Torrey Peters is published by Profile Books, and is out now.