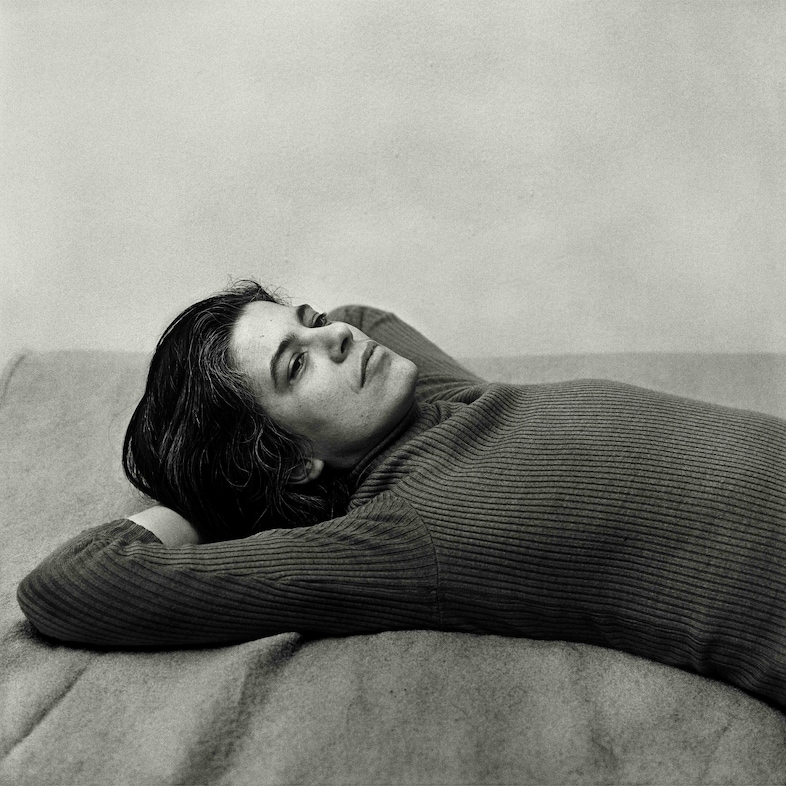

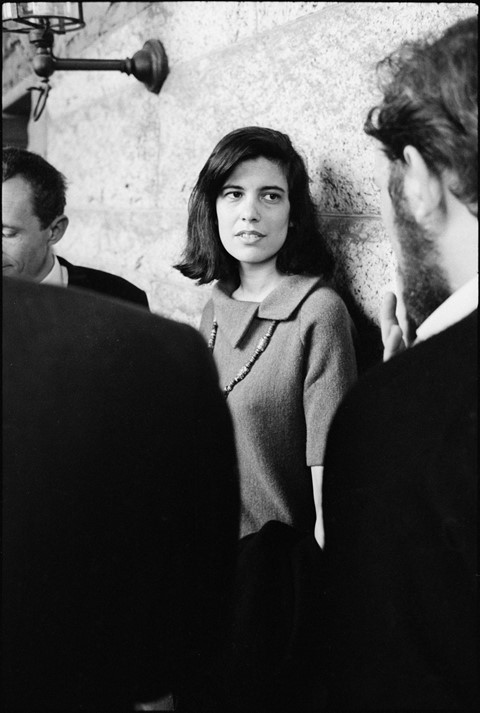

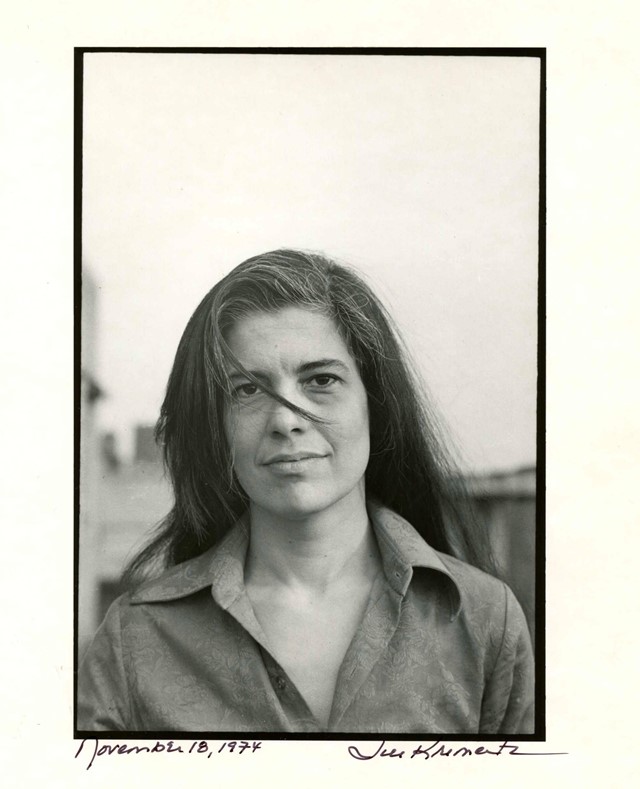

As her work is celebrated by two German institutions, we offer a five-point guide to the life and work of Susan Sontag, from her pioneering writing on photography, culture and cancer

Susan Sontag is one of the most famous cultural theorists of the 20th century. While she wrote extensively about the role of art, her view spanned far wider than the creative world itself. Her writing frequently interrogated the role – and failures – of photography in capturing the horrors of contemporary life and warfare. She flattened the imagined hierarchies that exist within culture, too. Her early essay Notes on Camp (1964) was described by The Guardian as a “cultural earthquake”, with Sontag examining the idea of camp as a collapse of so-called high and low culture. When countering Hilton Kramer’s critique of this paper, she said, “If I had to choose between The Doors and Dostoyevsky, then – of course – I’d choose Dostoyevsky. But do I have to choose?”

Born in New York in 1933, Sontag spent her professional life writing essays, novels, and short stories. She was also a political activist, publicly protesting the Vietnam War and basing her formidable cultural critiques on real-life visits to war zones, from Hanoi to Sarajevo. It has been over two decades since her death, but her writing is timelier than ever. Her ideas anticipated the flood of images that now proliferate the digital world, to which we have become ever more numb.

This spring, Sontag is being celebrated by two German institutions, with Susan Sontag: Seeing and Being Seen running at Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn until 28 September, and Susan Sontag: Everything Matters opening at Literaturhaus München on May 23. Below, AnOther runs through five key aspects of her prolific life and work.

1. On Photography has become a defining text on the medium

In 1970, Sontag joined a trip to Hanoi that was organized by the North Vietnamese government for US anti-war activists and writers. This visit had a powerful effect on Sontag, who released On Photography in 1977, exploring the political purpose of the camera and its passive, non-interventional role. She saw that photographs allowed those taking and viewing them to live life at one step removed. “To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have,” she wrote. In the contemporary world, her words are wholly fitting for self-image curation online: she asserted that the majority of people practice photography not as an art form, but as “a social rite, a defense against anxiety, and a tool of power”.

2. Regarding the Pain of Others questioned the passive gaze on real-life horrors

The last book Sontag ever published, 2003’s Regarding the Pain of Others examines the impact of photographs that depict human suffering. Informed by documentary images of war, and her own experience in conflict zones, this famous paper asks what’s really happening when we view violent images – especially those to which we have no tangible connection. Are we complicit? What does this constant passive viewing do to our sense of urgency and proactivity? “Compassion is an unstable emotion,” she wrote. “It needs to be translated into action, or it withers.” Since her death, these ideas have only become more urgent. This text is often quoted in connection with Israel’s genocidal attacks on Palestine, to which many on the outside have become resigned voyeurs.

3. Her production of Waiting for Godot placed art directly within a war zone

While much of Sontag’s work critiqued the role of art and photography, she did sometimes produce pieces herself. She visited Sarajevo with PEN International in 1993, during the Bosnian War. Upon her return to New York, she was contacted by Haris Pašović, the director of the MESS international theatre festival in Bosnia, who asked her to come back and create a piece of art. He wrote to her, “While you make the fog the real life and the real death are happening here. Move your fucking asses and make something real.” She took up his offer and staged a production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, with exhausted local actors and a set comprised of UN plastic sheets that were typically used as window covers to evade snipers. Her version included only the first act of the play, with the suggestion that those living in the war zone must wait for salvation.

4. While Illness as Metaphor followed Sontag’s cancer diagnosis, she described herself as “anti-biographical”

Unlike many cultural theorists and writers today, who weave biography and personal trauma through their texts, Sontag kept herself one step removed from her work, even when it veered directly into issues that impacted her life. Her 1978 book Illness as Metaphor was released one year after her world-renowned On Photography and three years after her first cancer diagnosis – the sickness that eventually killed her in 2004. Throughout Illness as Metaphor, in which she confronts the way sickness is spoken about and the way in which those who are ill are treated within the culture, she doesn’t mention her own diagnosis once.

5. Aids and Its Metaphors expanded her critique of the language of illness

In 1989, Sontag wrote Aids and Its Metaphors as a partner text to Illness as Metaphor, exploring how attitudes towards Aids were formed by society – and suggesting means that could dismantle the homophobic ideas that quickly surrounded it. “The effect of the military imagery on thinking about sickness and health is far from inconsequential,” she wrote. “It overmobilizes, it overdescribes, and it powerfully contributes to the excommunicating and stigmatizing of the ill.” The current exhibition Seeing and Being Seen addresses Sontag’s wider position within queer culture. She explored her own bisexuality in her journals, writing in 1961, “My desire to write is connected with my homosexuality. I need the identity as a weapon, to match the weapon that society has against me […] Being queer makes me feel more vulnerable. It increases my wish to hide, to be invisible – which I’ve always felt anyway.”

Susan Sontag: Seeing and Being Seen is on show at Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn until 28 September 2025. Susan Sontag: Everything Matters will run at Literaturhaus München in Munich from 23 May – 30 November 2025.