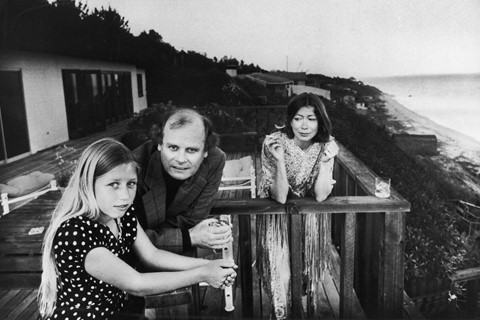

The Joan Didion most people think they know is made of a few well-worn images: a petite woman in oversized sunglasses, never smiling; an itemised packing list (two skirts, two jerseys, cigarettes, bourbon, and a mohair throw) and a highly-cited essay about leaving New York from 1967. These fragments have been quoted, referenced, repeated, and re-quoted into a distinct iconography: Saint Joan. But the person beneath the published voice remains elusive. By design, the mortal Joan stayed hidden. Despite the directness of her prose, one can never quite work out what she’s really trying to say. Now, with the opening of her archive and forthcoming publication of her diaries, that may be about to change.

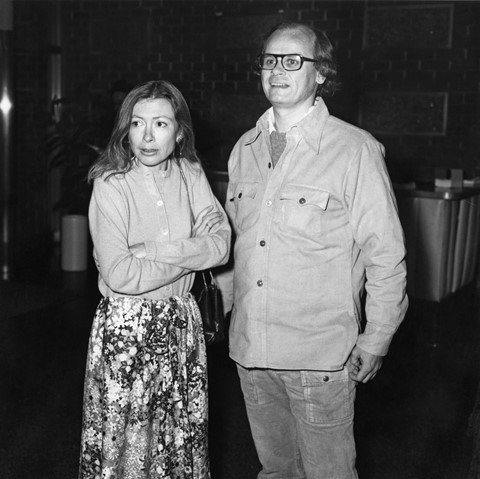

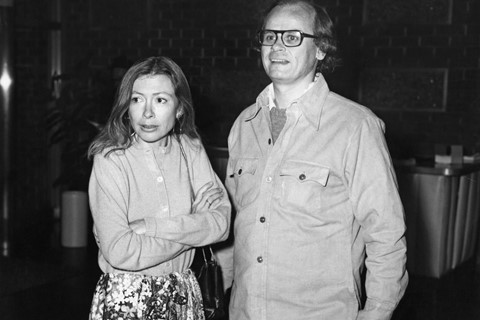

Didion died in December 2021 due to complications from Parkinson’s disease, leaving behind a legacy of 16 books as well as 336 boxes of archival materials. From transcripts to diary entries and personal letters, these boxes humanise the saviour who once walked on literary water. The archive, belonging to Didion and her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne (who passed away in 2003 after a heart attack), was recently acquired by the New York Public Library and can now be accessed by appointment, as of March 29. And later this month, on April 22, the publication of Notes to John – a posthumous book of largely unedited diary entries written after Didion began seeing a psychiatrist – offers an unfiltered glimpse into the mind of the New Journalism poster girl. It is in this moment, and perhaps for the first time, we can hope to see Didion as she saw the world: unwavering and unflinching, straight down the line.

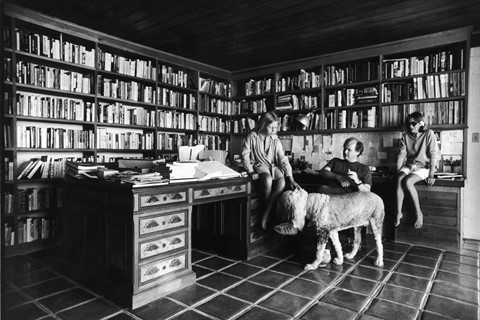

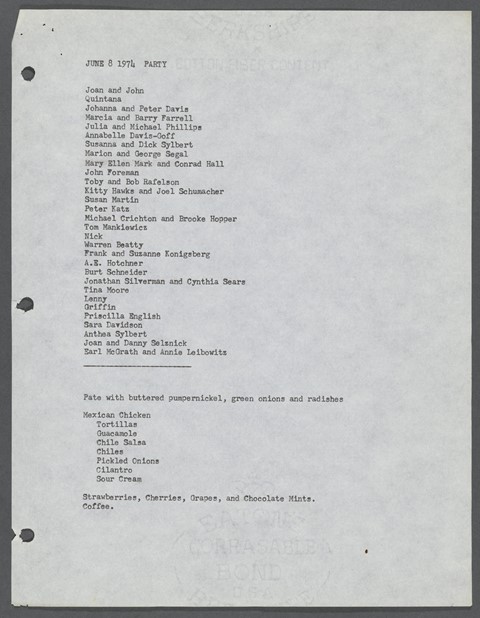

Didion’s archive is vast and exacting, complete with notes from interviews with The Doors, Linda Kasabian and Joan Baez; there’s also Joan’s baby book with clippings and hair; decades of “daybooks” written by herself and John, and over 140 letters tracing her voice during the seven years she worked at American Vogue. There are menus and guest lists from the couple’s glitterati dinner parties; RSVPs include Warren Beatty and Annie Leibovitz. Didion’s attention to detail is obsessive, almost indecent in its specificity, revealing, piece by piece, an image of the archpriestess of cool, caught smoking against that Corvette Stingray.

Olivia Laing, a writer who has made a career chronicling the lives of artists and writers, has previously described the act of visiting an archive as like talking to the dead, calling it a “strange business, summoning ghosts.” For Laing, the power of the archive lies not just in confronting the lost, but in its quiet ability to “summon over and over, forever maybe.” Lili Anolik, the author of Didion and Babitz (2024), a gorgeous joint biography of two American writers, also understands the power of the archive; it is where she got to know Eve Babitz – one of her subjects – intimately. “I never met the Eve who wrote those books I loved in the 1970s,” she says over email. “But reading these letters was like meeting that Eve.” Upon its publication last year, Anolik’s book sparked major controversy for describing Didion as “calculating” and “pitiless.” “She uses all these things, emphasizing her own frailty, to disguise the fact that she’s a predator,” Anolik writes in Didion and Babitz. “It’s the tininess, it’s the sunglasses, it’s the shyness. But she’s a killer.” This portrait only deepens the sense that Didion’s image was as impenetrable as it was deliberate.

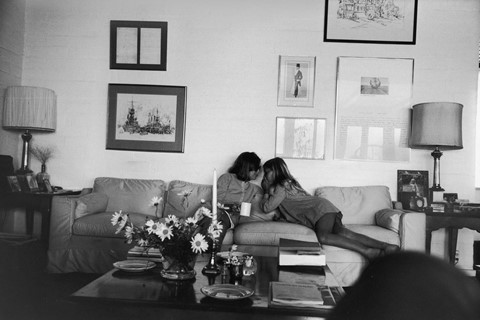

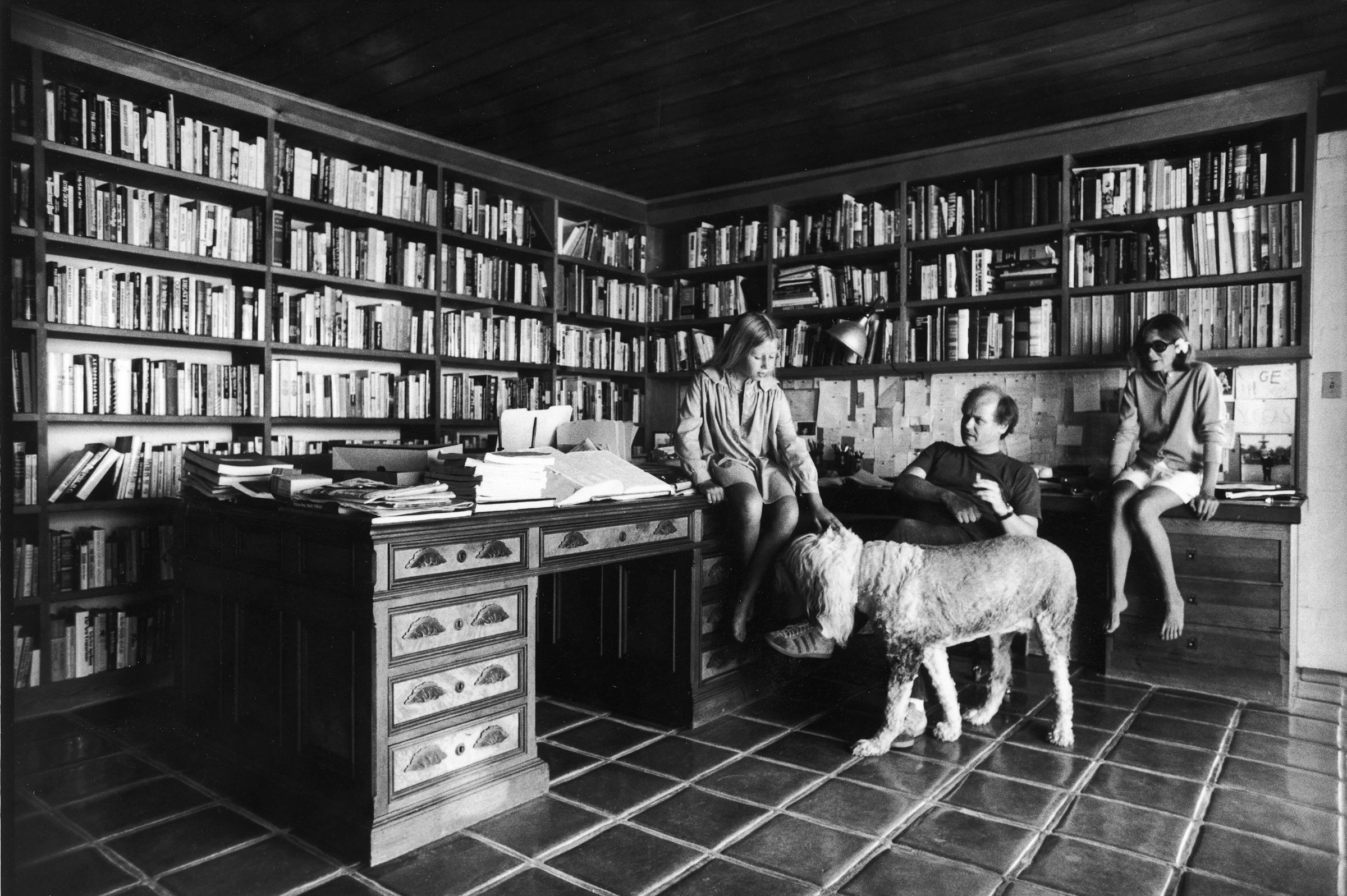

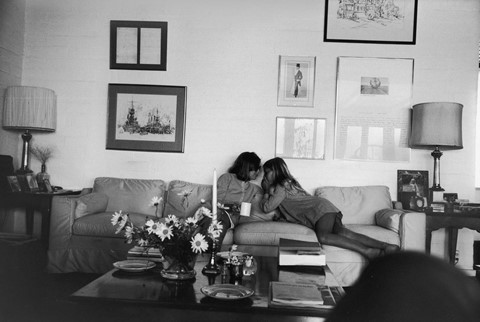

The NYPL archive proves that Didion and Dunne were keen observers, bound by a shared, meticulous instinct to document. Both passionate gossipers, the pair kept their receipts literally, tracking every expense, appointment, and prescription; a task that might seem tedious were it not punctuated by dinners with Edward Said, Patti Smith and Nora Ephron. We will learn more about the duo’s personal life and relationship in Notes to John, which offers a raw glimpse into Didion’s therapy sessions as she recalls them to Dunne, covering themes of alcoholism, depression, anxiety, guilt, and her complex relationship with her daughter, Quintana. Though a one-sided account, Didion’s voice – or Julianne Moore’s, if you listen to the audiobook – creates a sense of dialogue between the couple, revealing, if only slightly, an insight into their creative and romantic partnership.

In culture more broadly, as everyday life becomes increasingly digitised, the desire to document and sanctify physical ephemera continues to grow; film photography is back on the rise, as are handwritten letters. The lost and found of artists, writers, and thinkers have emerged as a vital and necessary component to the art world. Consider Dear Jean Pierre (2018), a book and exhibition of David Wojnarowicz’s love letters, or the upcoming publication of Stay Away from Nothing (2025) Paul Thek’s letters to his former lover Peter Hujar.

In a recent, moving piece for the London Review of Books , Colm Tóibín beautifully reflects on the loss of American writer and critic Gary Indiana’s library in the California fires, while Andy Warhol’s archive of over 3,600 digitised contact sheets at Stanford University offer glimpses into the person behind the mask and wig (and lest we forget, his quick-fire interview with Didion, covering regrets, first jobs, breakfast, New York, and dream dates). These repositories of the mundane offer a tactility to the divine figures who are at times intangible. The boxes are filled with eager seeds, ready to grow into new thinking, scholarship, or obsessions for future generations. When asked if archives are important for students today, Anolik responds simply: “Yes, fucking obviously!”

Since her passing, Didion’s influence has only grown, stretching far beyond her five foot one and three quarter inch frame (which she bumped up to five-two on her California driver’s license). While her iconic essay collections have long secured her place in the literary world, her renewed popularity has reached new cultural heights, cemented through exhibitions, play revivals, a hyped estate sale, countless biographies, and, of course, that 2017 Netflix documentary directed by Didion’s nephew Griffin Dunne. And now, with new access to her archive and the release of her letters, we’ll be granted an even rarer, more intimate glimpse into her world; here lies a chance to meet Didion’s gaze head-on, eye to eye, with only a waft of cigarette smoke breaking the silence.