Our new column offers a unique insight into London's most brilliant museums – first up, the Geffrye

I was looking for distraction when I went along to the Geffrye Museum on a recent Saturday afternoon. It was London's Open House weekend, and I followed drifts of people away from the noise of the Kingsland Road, into the calm, green courtyard of the museum. Built in 1714 by the Ironmongers’ Company at the bequest of Sir Robert Geffrye, the terrace of distinctively Georgian houses that hug the lawn was home to dozens of elderly poor for almost two centuries. The low row of fourteen two-story houses, each with their own smart olive green door, forms an inviting and protective c-shape around the grass. I thought of the anonymity of the tatty OAP homes that I knew in south London, which have little greenery of either sort.

A museum history

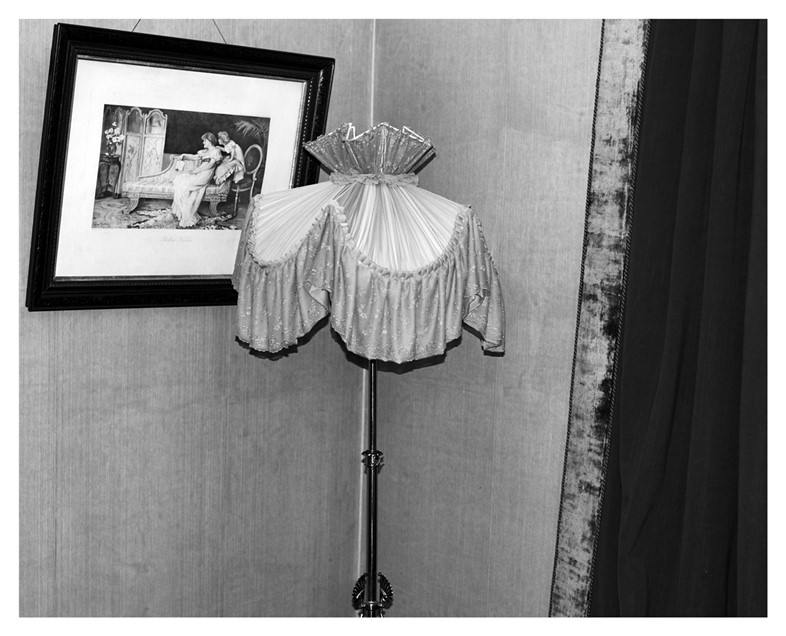

As a museum, it is exactly 100 years old, and the recreated almshouses are the most recent addition. Hoxton gradually lost its fields and market gardens as it became poorer and more crowded, and by the early 20th century the ironmongers relocated their pensioners to the healthier environs of Kent. In 1914 members of the Arts and Crafts movement campaigned for the buildings to be transformed into a museum that would educate people in the East End furniture trade, and today the buildings are Grade I listed, and the focus continues to be on the home. The main museum is a walk through time, as you pass chronologically through the living rooms of urban middle-class English households from 1600 up until a ‘loft style apartment’ from 1998. They are interrupted only by the central Chapel – where residents had to attend services every week – which has been left intact with its incredibly upright booths of pews and gold Ten Commandments written in large spidery letters on the walls.

Insights into living

Open House meant that I could also see inside No. 14 – a recently restored almshouse, open only sporadically. Downstairs is now furnished to show how a resident’s room would have looked in 1780, while upstairs recreates the slightly plusher living conditions of 1880. The house was candle-lit, which showed off all the original woodwork, and of course, the ironmongery. It showed living arrangements almost at their simplest: each resident or couple were allocated just a single room within the house. There was a bed in the corner, a fireplace, a few pieces of furniture, and a small pantry. Downstairs was a large, shared butler’s sink for laundry.

"The rooms felt familiar, poised, ready for human action, and illustrate the consistency of two basic desires: to live with independence and with pride"

Perhaps we are meant to think sorrowfully of lonely old men boiling vegetables for a whole day over the fire to make their gruel, as apparently they once did. But looking out of the butter-coloured sash windows onto the lawn, I began to envy the museum director that got to live here before its restoration. The scale of the rooms was pleasing. It was quiet, but didn’t feel isolated or overlooked. In fact, gruel and laundry arrangements aside, I was envious of its 18th and 19th century residents; probably not the intended, or appropriate, reaction to the ‘glimpse into the lives of London’s poor and elderly’, that the museum hopes to give.

"To live with independence and with pride"

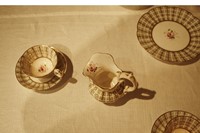

Focusing on the ordinary things that are chosen to make a home acknowledges the significance of our immediate surroundings, and how, as Virginia Woolf once wrote, objects can "enforce memories of our own experience". Obviously there have been changes over the years to how people order the insides of their houses, most evident in objects from abroad – rugs from Turkey, porcelain from China – making their way into the home, and staying as the decades progressed; and no doubt the Geffrye Museum does show the tastefully tinted version of what life was actually like in one of the almshouses. But there is comfort to be had from knowing that, at the domestic level, a similar aesthetic is still pursued, often at great expense, even after 400 years. The rooms felt familiar, poised, ready for human action, and illustrate the consistency of two basic desires: to live with independence and with pride, enough to want to share these private spaces with others (and hopefully provoke some healthy jealousy in the process). It was a great distraction, particularly at the time of year that encourages a retreat into warm interior spaces; but far from being about the old and dying, the Geffrye Museum really is full of living rooms, in every respect.

The Geffrye Museum, Kingsland Road, London, is open Tuesday-Sunday, 10am-5pm.

Words by Lily Le Brun