Enter a spectral, skeletal world exploring evolution and anatomy at the Grant Museum of Zoology, captured by Chris Rhodes

I once dissected a rat: put nails into its pink paws and pinned it to a wooden board, made a shallow incision in its throat with a scalpel, and, using scissors, snipped off its white fur coat. Everything had its place, packed neatly in and around a delicate skeleton. A thin, almost translucent layer of purple muscle covered its organs, which seemed to be individually colour-coded, as if they could be taken out and put back together with ease. Seeing the hidden logic was a revelation, as was how similar everything looked to pictures of the human anatomy that were in our biology textbooks.

It was only relatively recently that science confirmed that 97.5% of our DNA is the same as a rodent. But early scientists such as Robert Edmond Grant, after whom the Grant Museum of Zoology is named, guessed at it by cataloguing and comparing the anatomies of as many animals – including humans – as possible. They built great collections of creatures that they dissected, stripped to their skeletons, stuffed or suspended in liquid in jars. It might sound macabre, but it did important work: one of Grant’s pupils was the man who developed the theory of evolution, Charles Darwin.

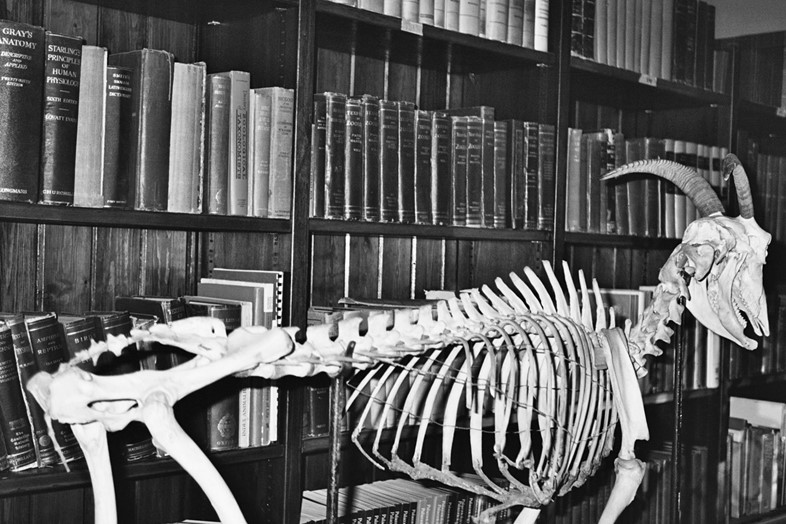

Grant was made the first Professor of Zoology at the brand new University College London in 1827, and was the first person to teach comparative anatomy in Britain, a method that is still used today. During his lifetime, he collected together thousands of animal specimens in order to teach: preserving them in alcohol, mounting their skeletons, and providing something for his students to dissect. Later, other whole zoological collections were added as well as individual items from London Zoo, such as the anaconda, whose 5 metre long skeleton, spiky with hundreds of rib bones, is displayed draped in a coil around a branch of a tree.

All this now forms the Grant Museum of Zoology in Bloomsbury, which is one of the oldest natural history collections in the world. Although it has moved around quite a bit since Grant’s teaching days, (including the time when the entire lot was shipped out to Bangor during the Blitz) it has maintained its traditional taxonomical display – i.e. the animals are shown in groups of those judged to be most similar to each other. The close ranks of dark wooden shelves, drawers and glass cupboards are filled to the brim with strange beasts, and there is more than a passing resemblance to the cabinets of curiosity that were once common in musty Victorian museums; some of the vitrines date back to The Great Exhibition of 1851.

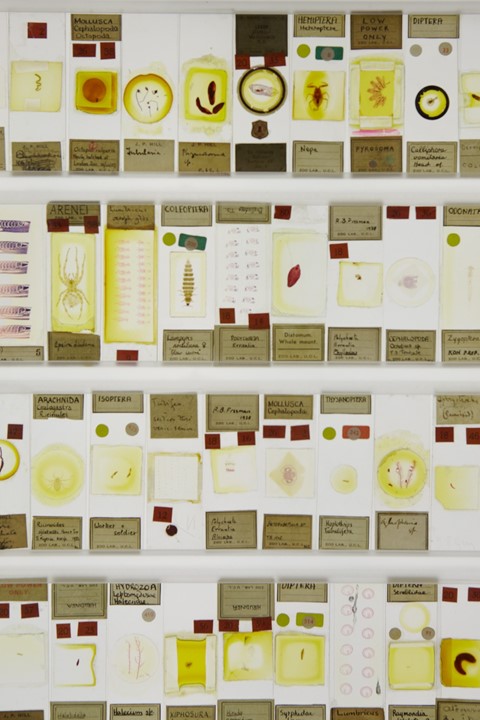

The Grant’s 70,000 animal specimens represent the great and the small, ranging from the skull of an elephant to a flea’s leg. A corner of the museum has even been converted into a micrarium – a sort of walk-in light box packed wall to wall with microscopic slides – where they manage to show over 2000 of the tinier things, like insect wings, fibres taken from a giraffe horn, a strand of mammoth hair, and a very miniature squid.

Even if you have only a sliver of the interest Grant himself took in the anatomical intricacies of the animal kingdom, it is difficult not to be beguiled by the range of exotic oddities that crowd the museum. Jars filled with dense tangles of snakes; a pair of eagle owl talons; the mandible of a thylacine; blackened dodo bones; the brain of a tiger cub; the skeleton of a spotted-tail quoll; the 3 metre wide, 7000 year old fossilised antlers of a giant elk… it is a collection of the truly curious that cannot fail to intrigue.

Words by Lily Le Brun