We look to the future and the extraordinary question of how to communicate with the humans 10,000 years ahead

Contemplation of the deep future is often confined to the alternative universes and super-galactic stories of science fiction. But we wanted to consider the few things that are real now and will likely survive many millennia after we're gone, stuff that reaches to the edges of fact and fiction. Here are three things that for better or for worse will outlive us all by a long shot:

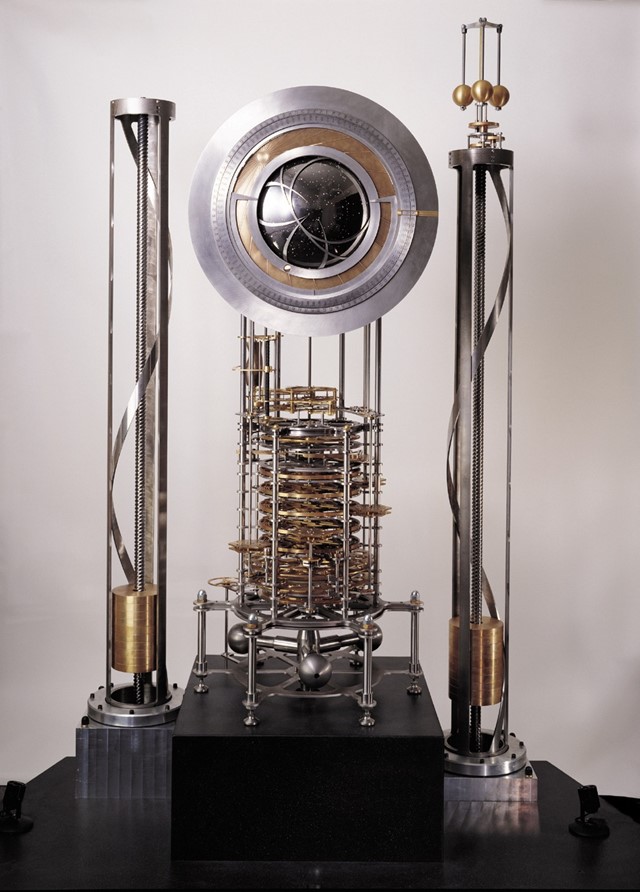

The Clock of the Long Now

The Long Now Foundation is a cultural institution dedicated to long-term thinking with the legendary Stewart Brand, creator of the Whole Earth Catalog, at its helm. Their initial project is a mechanical clock which is built to tick until the year 10,000, deep in a rock in western Texas. To construct this clock is a huge ongoing challenge, to make something that will last millennia means the makers have had to think very differently about the materials they use and the scale of the device. The clock will be over 60 metres tall, a spiralling spectacle assembled in high desert dirt, a day’s trek from the closest road, a point of pilgrimage for thousands of years to come.

Into Eternity

The Long Now Clock is a purposeful ode to the future. But there are some remnants of our civilisation that will unintentionally survive and even remain hazardous to the year 10,000 and beyond – high-level nuclear waste, the leftovers from nuclear power plants. There is still no accepted place to deal with this waste, although the Onkalo deep underground repository in Finland is set to be ready in 2020 and will be the first functioning site of its kind. The tensions that surround this project are elegantly documented by Danish director Michael Madsen in the film Into Eternity. Scientists confirm that this site will remain deadly for many years to come; but a fascinating focus of the film is our responsibility to notify future generations of the risk if they were to dig there. To design communication over these time scales is unfathomable; these extreme challenges gave birth to a whole new field in the 80s – nuclear semiotics – focused on the best way to alert sentient beings to harmful nuclear waste sites when languages and even humans may no longer exist.

The Last Pictures

Another set of deep-time artefacts glide around us daily, up beyond the outer reaches of the atmosphere: satellites. Some satellites power our GPS tracking, satellite TV or take precise imagery of earth, but a few hundred have finished their lifecycle and exist indefinitely in the graveyard orbit – the place many satellites go to rest in peace when they are no longer in use. As artist Trevor Paglen poetically highlights in the documentation for his project The Last Pictures, satellites are fossils of the future; technological remnants likely to outlive the human race in the largely antiseptic environment of space. Intrigued by the longevity of these orbiting bodies, Paglen worked with material scientists at MIT to engineer a micro-etched disc with 100 curated photographs, set to be ‘The Last Pictures’, which now live on the satellite EchoStar XVI, a human message trapped in the aeons of space.

A short exploration of the our generation’s long-term legacy brings a new perspective to the present, it pushes us to question what mark will we leave on the earth and beyond? It turns out we leave quite an odd legacy of artefacts for far-future life, unless in the year 10,000 humans have evolved to be creatures that thrive in radioactive landscapes, covet shiny space shrapnel and still stick to the same time.