The former Lambeth Workhouse is now a cinephile's heaven, filled with the treasures of film past and present

Martin from the Cinema Museum in Kennington is aghast. ”You’ve never heard of Roy Hudd?” he asks incredulously, horrified at my ignorance. Roy Hudd, he tells me with the authority that you might expect from a man who has devoted much of his life to entertainment history, is a former star and now leading historian of the music hall. He will be giving a sold-out talk at the museum later that evening. The Cinema Museum is the sort of place, I quickly learn, that hosts cinema history Wikipedia editathons and crime film courses; these cinephiles will not be found live-tweeting the Oscars.

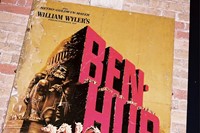

Run entirely by volunteers, it is the only museum in the UK dedicated to the history of going to the pictures, covering the 1890s to the present day. It all began in 1979, when Martin joined his partner Ronald, a cinema projectionist from the age of 15, in salvaging the guts of cinemas that were closing all over Britain. Since the 1960s their huge spaces were being repurposed for more profitable enterprises, and the heyday of cinema going seemed to be over. The pair rescued the banks of velvet seats, the gilded signage, the jauntily patterned carpets, the faded posters, the ticket booth counters, the ushers’ uniforms, the machines and the film reels – over 17 million feet of it. They even rescued ashtrays, 3D glasses and popcorn cartons. By the mid 1980s, they had collected so much that they moved their finds into the former administrative offices of the Lambeth Workhouse, where, suitably enough, Charlie Chaplin – born into poverty down the road in Walworth – once lived as a child.

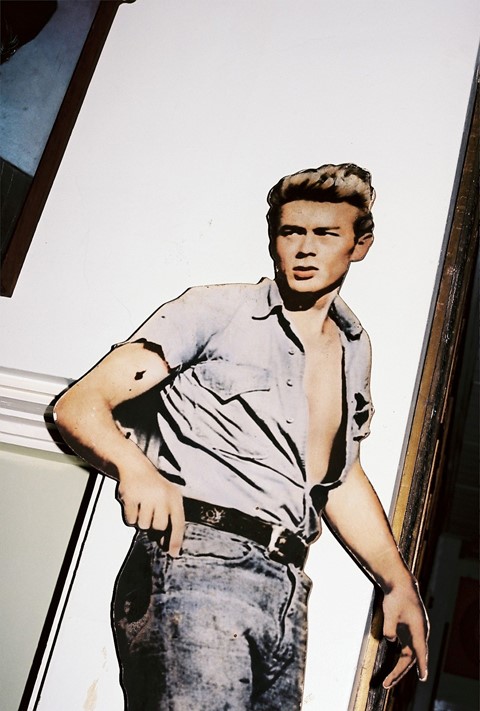

Donations from other film aficionados are continually being added to their collection, and today their reclaimed treasures line the museum’s large corridors in a hodgepodge celebration of every aspect of the cinema experience. Between the 1920s and 1960s cinema going was a central part of normal life. “They were palaces of entertainment.” Martin says. “It was a very important part of a huge number of people’s lives: lots of people went to the cinema twice a week. And they would be going to an Odeon or a Grand cinema which was very luxurious, very different probably from the surroundings in which they lived generally, so it was a very important cultural influence on people, the buildings as much as the films that they would go and see.”

There’s an astoundingly comprehensive archive, with complete runs of trade magazines from their first issue to their last, architectural plans and decorative schemes for cinema buildings, books of film criticism and manuscripts of music, as well as original poster artwork. There are over a million photographic images, documenting the ordinary visitors and staff as well as the stars on the screen. The Museum has also done important work to restore films: 75 Mitchell and Kenyon titles, for example, dating from 1899-1906.

It’s not all condemned to history, hidden away in shelves and film canisters and filing cabinets. Martin and Ronald give tours and regularly host events and screenings, whirring silent films into life with live piano accompaniment. At the risk of sounding Hollywood corny about their life's project, they are making sure that an activity that has brought enjoyment, distraction, hope and ambition to so many people, is being applauded long after the credits have rolled.

The Cinema Museum, 2 Dugard Way, SE11 4TH, can be viewed most days if pre-booked in advance. Contact here to arrange your visit.