We take a lesson in practical madness from Piero Fornasetti, the master of imaginative decoration

"I have gathered thousands of documents on the so-called decorative arts; it is essential to find, to collect things together so that at the right moment I can find an aesthetic reference to use for my creations, and it gives me a sense of tranquillity, another satisfaction of the collector." So said Piero Fornasetti, master of the decorative imagination, whose playful and humorous designs famously transformed furniture into objets d'art, defined by a signature humour. As suggested by this statement, Fornasetti was a great assimilator of ideas, always open to new concepts and movements, from which he would then extract his favourite principles to apply to his whimsical creations.

He was a great craftsman, able in glassmaking, ceramics, textile design, woodwork and papermaking. First and foremost, however, he was a graphic artist for whom the line and the stroke were of the utmost importance. Now Practical Madness, a new book from Thames and Hudson – coinciding with a major retrospective at Les Arts Decoratifs in Paris – honours the designer's endless invention, setting out his visual puns and decorative devices in the context of his paintings, a lesser-known but fascinating facet of his work. Here, in celebration of the book's release and of Fornasetti himself, we explore five of Fornasetti's key influences.

Architecture

It was while studying applied arts, in a series of night classes at the Castello Sforza, that Fornasetti discovered his love of architecture – a passion that would last a lifetime. He saw it as the highest expression of drawing according to the principles pioneered by Classical and Renaissance artists, and many of his future designs directly referenced the architecture of both eras. The majority of these were the result of his partnership with the architect Gio Ponti, whom he met in the 1930s and collaborated with for many years on a very varied range of projects. Ponti gave Fornasetti the confidence to bypass the limitations of painting to explore other media, strong in the knowledge that once the laws of drawing has been assimilated, anything was possible – from the creation of decorative objects, fashion and furnishings to interior design.

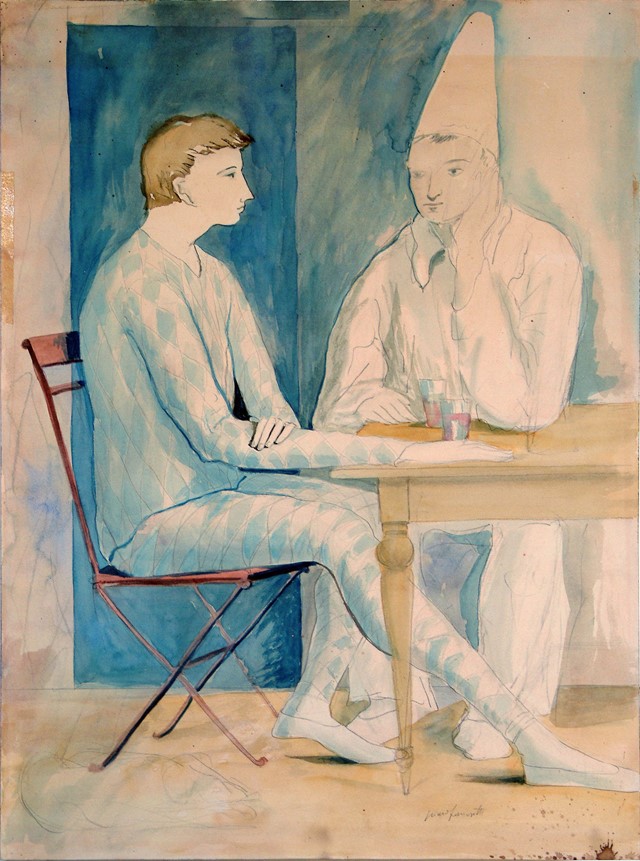

Picasso

The work of Picasso was also of great influence to Fornasetti, who experimented with playful, Picasso-esque line drawings throughout the 1940s, and later with the use of newsprint as a decorative medium just as the Cubist pioneer had done before him. Meanwhile, one of our favourite of his Picasso inspired works is 1949 painting Arlecchini (Harlequins), which in tone and subject matter evokes Picasso's turn-of-the-century Blue Period works.

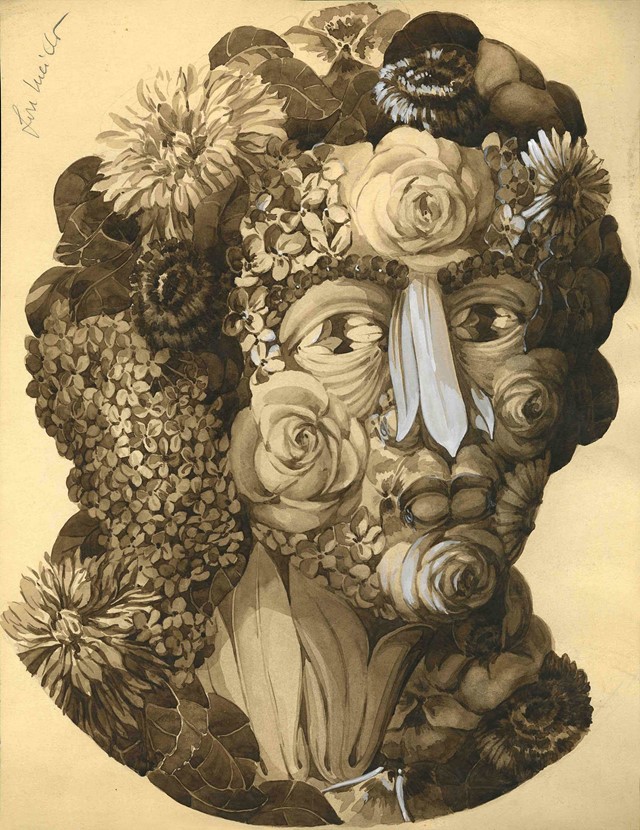

Surrealism

The creation of dreamlike and evocative atmospheres within his designs was a defining facet of Fornasetti's aesthetic and was driven by his interest in Surrealism and "pittura metafisica" (Metaphysical art). He once noted, “The artist must put order in things to create another world, a second nature.” Fornasetti mirrored the work of the Surrealists not only in his fondness for fantasy but also in his compulsion for repetition (think the myriad variations of the female face now so synonymous with him name), as well as the use of feminine iconography and the often fetishistic insistence on a limited set of loaded imagery – from sunflowers to fish to Roman architecture.

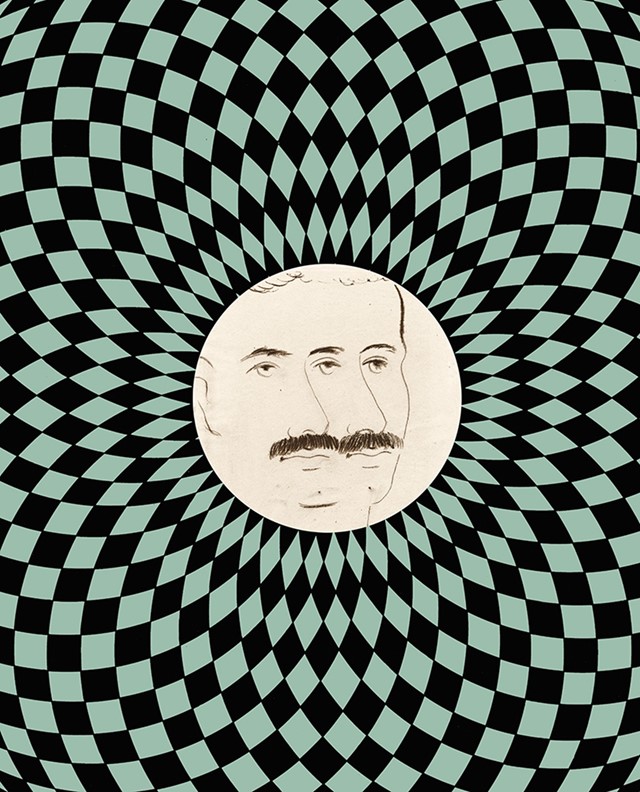

Op Art

When Op Art – "a form of abstract art which relies on optical illusions in order to fool the eye of the viewer" – emerged in the early 1960s, Fornasetti was quick to jump on the bandwagon, adopting its abstract techniques and applying them to a variety of objects, from mirrors to plates, to dizzying, undulating effect.

Renaissance Art

Fornasetti openly acknowledged a fundamental debt to two publications, Carlo Carrà's Giotto and Roberto Longhi's Piero della Francesca, demonstrating the importance of Italian Renaissance painting upon his work. He was inspired by the return to order for which the Renaissance artists strove. This is reflected in a number of his 1940s paintings which demonstrate the use of pure lines, restrained colour ranges and the recourse to classicising gestures and themes, as well as a fondness for a certain monumantality. Echoes of the Renaissance appear throughout Fornasetti's oeuvre but often he would adapt or subvert its principles in pursuit of 'follia pratica' – the desire to “put 'reason' at the service of 'unreason',” perhaps the most defining principle of his artistic practice.

Piero Fornasetti: Practical Madness is out now, published by Thames and Hudson.