The vast collection of a Victorian game hunter is transformed into an extraordinary mission of conservationism at Quex Park

When a lion attacked Major Percy Horace Gordon Powell-Cotton, a copy of Punch magazine that was folded in his pocket saved him. Apparently, it prevented his abdomen from being ripped open before the porters accompanying the Major on his African safari were able to shoot the lion dead. The defeated creature was sent home to the Major’s ancestral country estate, where it was stuffed, and displayed it at its most ferocious, sinking its teeth into an enormous buffalo. The close encounter was even immortalised by the popular satirical magazine in a poem: 'The wounded lion with a lusty roar/ Advanced to drink the gallant Major's gore; But suffered great confusion when he felt/ An unexpected Punch below the belt.'

For a spiffing tale of Edwardian derring-do, it doesn't get much more stereotypical than that. But although he wore a pith helmet and shot many, many animals, Major Powell-Cotton wasn't simply a bloodthirsty, indiscriminate hunter. His principal concern was with categorisation and conservation. The result of this twin obsession formed an incredibly ambitious – but little-known - natural history and ethnographic private museum, now the remarkable Powell-Cotton Museum at his former home, Quex Park House in Kent.

Major Powell-Cotton’s aim was to preserve and record representative specimens of the fauna he saw in the course of the 28 trips he made to Asia and Africa. Trophies alone didn’t interest him – he wanted the male, the female, the juvenile and the one with the slightly wonky horns. The selected species were shipped home (sometimes in empty champagne crates) where his curator was waiting to label them in neat black pen, put them into careful storage, or send to the taxidermist.

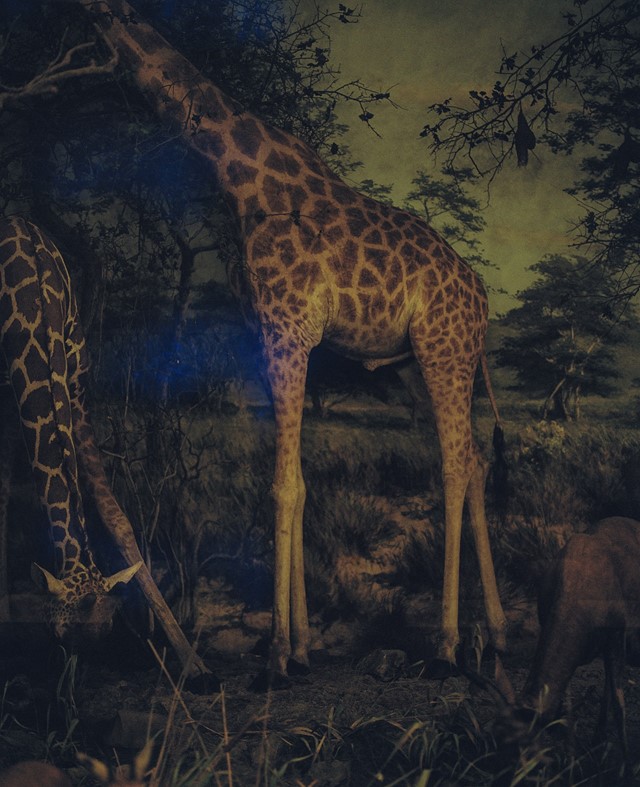

The Major built a museum directly adjacent to his house, where he constructed huge dioramas. Elaborate and eccentric, they recreate whole scenes from his travels and remain at the core of the museum today. One, depicting the Himalayan landscape at dawn, is the oldest in the world. Another shows a vast bull elephant charging from the bushes, scattering various smaller creatures with its eleven-foot long legs.

Major Powell-Cotton started his travels in 1889, when photography was in its infancy and long before cheap travel. Getting hold of the physical specimens was often the only way that early naturalists could study animals. He made detailed field notes, and the material he collected is still used today by scientists for research. Several species are even named after him.

The Major was also interested in the ethnographic dimensions of his journeys, bringing home thousands of objects bought or given to him by the communities he met. Extraordinarily for the time, his daughters accompanied him on a few of the trips and later became pioneering anthropologists in their own right, taking a more sensitive approach to their father. Worried that a colonial presence would change the communities they had come to know, in the late 1930s they made two trips to Angola, making over 30 films and bringing back nearly 3000 objects – one of the largest collections of Angolan material culture in Europe.

Like his daughters, the Museum has recognised that times have moved on since Major Powell-Cotton’s collecting days. Arts Council funding has recently meant that they have been able to build a new gallery where some of these exotic objects can be handled and learned about in depth. Making the most of the Powell-Cottons’ extensive and thorough research, the aim is to fuel a new generation of curious minds, at a safe distance from any lion claws.

The Powell-Cotton Museum at Quex Park, Park Lane, Kent, CT7 0BH is open Tuesday-Sunday, and Bank Holiday Mondays.