In celebration of revolutionary sign language drama The Tribe, we discover more of cinema's most important firsts

This month, one film has got everybody talking – which is ironic because the movie itself contains no talking whatsoever – award-winning drama The Tribe by Ukrainian director Myroslav Slaboshpytskiy. The story of a deaf mute teenager struggling to fit in at a specialist boarding school that is rife with criminal activity, it is performed entirely in sign language with no subtitles or music, leaving the audience to construct their own dialogue using nothing but the characters' gestures and expressions as a guide. Completely redefining the standard perception of the silent movie genre, it is a completely immersive and deeply cathartic experience, that shocks, disturbs and intrigues in equal measure, pushing at the boundaries of cinematic convention. Here, in celebration of a soon-to-be cult classic, we discover five other movies which, through sheer daring and originality, have changed the landscape of film.

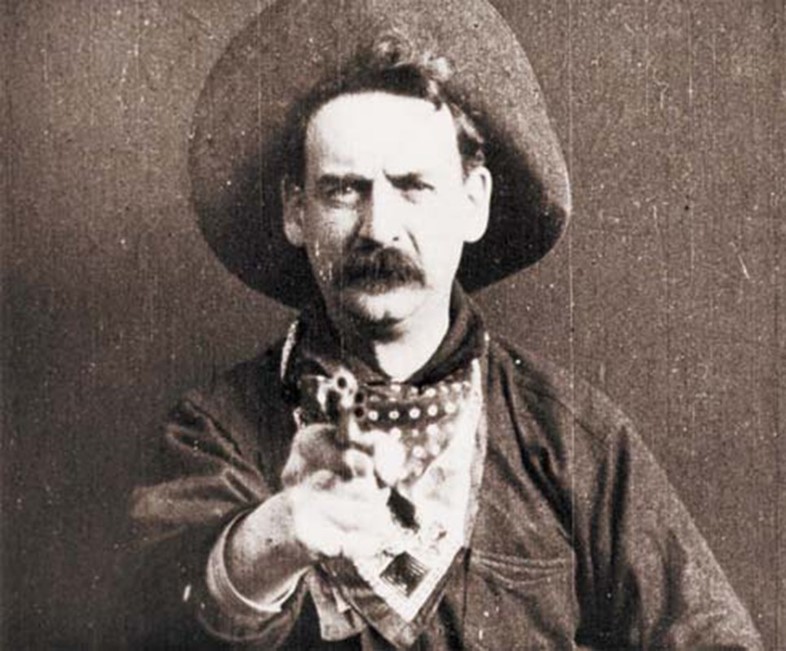

The Great Train Robbery (1903)

Shot in 1903, The Great Train Robbery is widely considered to be the first American action film and the first fully formed Western. Written, produced and directed by Edwin S. Porter, formerly a cameraman at Edison Studios, the simple narrative consists of 14 linear scenes following a group of bandits as they hijack a train, commit a robbery and eventually meet their sticky end, all in the course of ten minutes. The film boasts a number of innovative techniques from composite editing to camera movement and on-location shooting, as well as being one of the first to use the technique of cross cutting, whereby two scenes appear to occur simultaneously but in different locations. It was so extremely realistic that it wreaked havoc among viewers, with audiences members fleeing theatres to avoid the "on-coming" train and screaming as a gunman fired bullets into camera in the famous final scene. It is even said that, during one screening, a sheriff in the audience stood up and fired back causing damage to the screen and surrounding walls.

M (1931)

Fritz Lang's M is often referred to as sound cinema's first true masterpiece. The film – which sees a chilling Peter Lorre as child killer Hans Beckert – was Lang's first experiment in sound and is particularly notable for its dense and complex soundtrack, which set it apart from the "talkies" of the time. This comprises the use of a narrator, sounds occurring off-camera as a method of narrative continuation and suspenseful moments of silence before sudden noise. Its most powerful employment of sound, however, is the murderer's telltale whistle which eventually gives him away to the blind vendor, resulting in his downfall. Amusingly, Lorre could not whistle and so it is Thea von Harbou, Lang's wife and co-writer, whose whistle has gone down in cinema history.

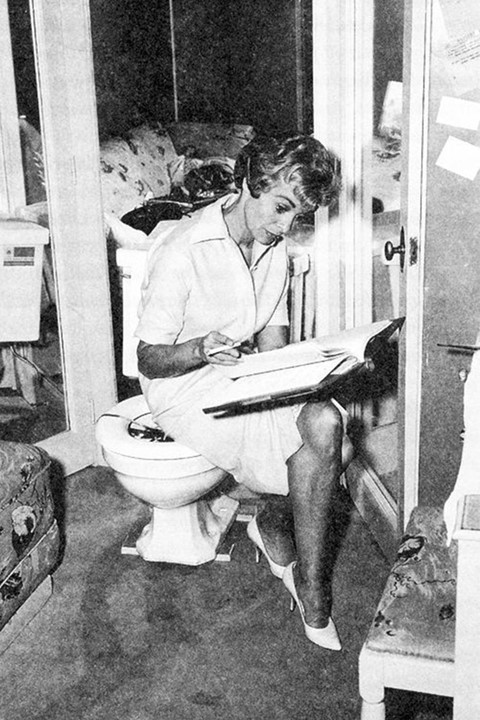

Psycho (1960)

Independently financed by Alfred Hitchcock himself (Paramount deemed it "too repulsive") and adapted from Robert Bloch’s 1959 novel, Psycho is still regarded as one of the most shocking movies ever made. Shot almost entirely with 50mm lenses on 35mm cameras to mimic normal human vision, it tells the story of ill-fated secretary Marion Crane and maniacal motel owner Norman Bates; and when it comes to Hollywood firsts, it really sweeps the board. It is hailed as the first ever slasher movie and was the first to risk the early death of a heroine. It was the first to hint at necrophiliac incest (how surprising!), and more remarkably the first to show the practical use of a toilet on screen. But it was the opening scene, featuring the unmarried Crane and Sam Loomis sharing a bed that most appalled puritan viewers.

Basic Instinct (1992)

One hopes the aforementioned puritans didn't make it to see Basic Instinct 32 years later, for they'd have been in for a shock. But although the overt depiction of carnal desire and graphic violence prompted outrage among some viewers at the time, Paul Verhoeven's iconic thriller is contemporarily celebrated for its groundbreaking depictions of sexuality in mainstream Hollywood cinema, while its infamous leg-crossing scene broke a taboo that even lead actress Sharon Stone claims to have been unaware of. Sunday Times critic Shannon J. Harvey called it one of the finest productions of the 1990s, crediting it with "doing more for female empowerment than any feminist rally."

Boyhood (2014)

One of the biggest game changers in contemporary cinema has to be Richard Linklater's 2014 hit, Boyhood. Filmed over twelve years using the same cast, the film tells the story of Mason Evans (Ellar Coltrane) and the highs and lows that punctuate his life, and that of his family, between the ages of six and eighteen. Linklater began the movie without a set script, allowing the actors to be included in the writing process using their personal experiences to build and shape the narrative. The result is a compelling epic that is "Tolstoy-esque in scope" and, much like The Tribe, utterly original in format, going to show that film as a medium still has many avenues to be explored by future generations.

The Tribe is out now.