super/collider takes us into the depths of the Mayan jungle, for a study in human fragility

Where on Earth?

Petén, Guatemala

GPS Coordinates: 17°22′N 89°62′W

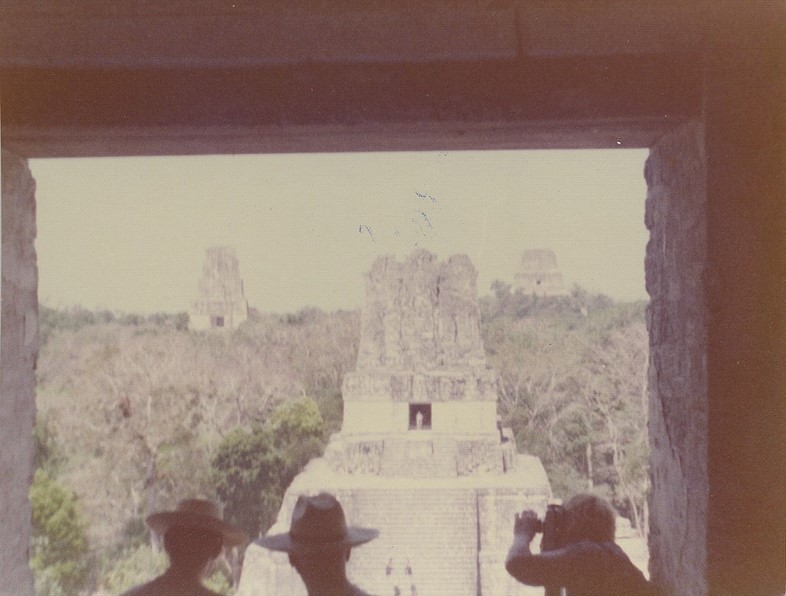

It’s dawn high above the rainforest, and from the canopy level below us comes the primordial sound of the forest waking up. We’re sitting quietly at the top of Temple IV at Tikal, the highest pre-Columbian structure still standing in the Americas. Birds, howler monkeys and other early risers call out across the vast forest stretching before us, as the mist slowly gives way to the sun. If we’d been here around the year 800, smoke from fires and the morning sounds of a busy city coming to life would be drifting up from the plazas below. But today, more than a millennium later, nature has once again taken over this part of the planet.

Located in what is now Guatemala, Tikal was one of the biggest Mayan cities, reaching its cultural peak between 200 and 900AD before suddenly collapsing, along with much of the rest of the Classic Period Maya civilisation, shortly thereafter. There are lots of different theories about why this happened, but the leading hypothesis is a combination of drought and climate change conspiring to create conflict, resource overexploitation and ecological collapse. If that sounds worryingly familiar, it should. The real impact of Tikal and similar sites today isn’t just in their monumental architecture, but the fact they could be foreshadows of our own fate. Perched on Temple IV under the increasingly hot sun of the 21st century, one can’t help but wonder if future travellers will climb the sand-swept ruins of Dubai, or marvel at deciduous forests stretching out across Manhattan and the five boroughs.

What on Earth?

Beyond serving as funerary temples for Mayan kings, the six large pyramids at Tikal may have worked together as astronomical observatories, helping priests to track the passage of time and mark important dates. The sightline between Temple I and Temple IV, for instance, records the position of sunset on August 13, the day the world began, according to the Maya. The so-called ‘E Group’ of buildings, meanwhile, appear to have served as a solar observatory to track solstices and equinoxes.

The collapse of the giant city – home to at least 60,000 people and covering more than 47 square miles – handed power back to nature, which soon went to work on the overexploited soil. Today, Tikal stands near the edge of vast (and in places lawless) expanse of rainforest: the Maya Biosphere Reserve – one of the last great wildernesses in Central America. Trees now competing with the ruins include the towering kapok, Honduras mahogany and tropical cedar. Amid the branches and dense forest floor lives a long list of species including agouti, white-nosed coatis, guans, toucans, green parrots, leafcutter ants, grey foxes, spider monkeys, howler monkeys, harpy eagles, ocellated turkeys, jaguars, jaguarundis, pumas, cougars, tapirs, macaws and deer.

How on Earth?

Though a little out the way, Tikal can be reached from southern Mexico, Belize and other parts of Guatemala, with the Maya Biosphere Reserve stretching into all three countries. Instead of flying into Flores with the tourists, take a more eco-friendly overland journey to appreciate the scale and distances involved. To watch sunrise at Temple IV, AnOther recommends the charmingly retro Jungle Lodge just outside the park, which was built during the 1950s heyday of Tikal archeology and features old photographs from the era.