The standout movies at this year's LFF shared a common theme: powerful women – in front of and behind the camera

Within the rich and diverse roster of movies shown at the 59th edition of the BFI London Film Festival, a prevailing theme emerged – powerful women – in front of and behind the camera. In addition to Sarah Gavron's headlining movie Suffragette, which passionately depicts the fight for women's suffrage, the swathe of acclaim for female filmmakers (which are inevitably still few and far between) and their inspired leading ladies feels like a triumph in the male-dominated world of film and media. Here, we highlight the movies that are bound to inspire...

Sunset Song by Terence Davies, 2015

Home-grown auteur Terence Davies returns with Sunset Song: set in austere, rural pre-WWI Scotland, the film treats nature’s capacity to endure as metaphor for a particularly female kind of strength and intuition. Under the multiple yokes of strict patriarchy, labour exploitation and a bleak future of harrowing childbirths, farmer’s daughter Chris Guthrie (a solid acting debut from supermodel Agyness Deyn), fights to retain the tenacity and tenderness of her spirit.

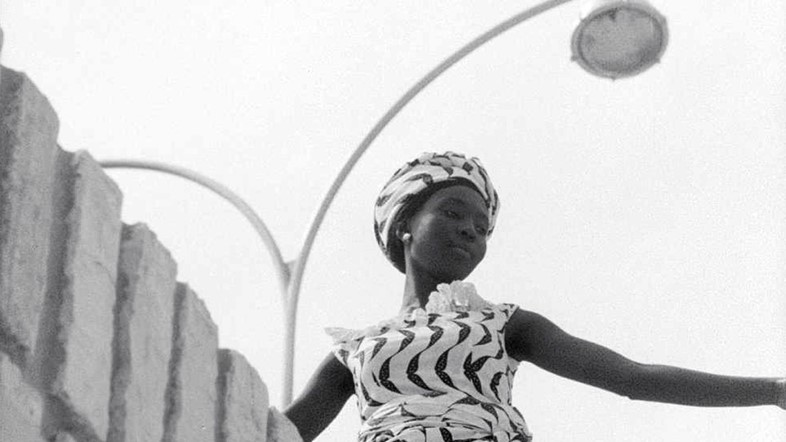

Black Girl by Ousmane Sembène, 1966

This year the LFF paid tribute to a father of African cinema, Ousmane Sembène. His Black Girl (1966) is a study of the enduring structures of racial and gender exploitation after decolonisation. Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), an au pair accompanying her white employers from Dakar to France, finds she is expected to be a domestic slave in all but name. Her defiance is met with the hypocritical concern of a 1960s West barely past their recent history of open colonial oppression; her act of finally reclaiming power over her own body and identity is drastic, but takes immense courage.

3000 Nights by Mai Masri, 2015

3000 Nights follows schoolteacher Layal (Maisa Abd Elhadi), imprisoned in 1980s Palestine for refusing to testify against an innocent teenager. Discovering her pregnancy soon after her decision to have and raise the baby, defying both her husband and her bleak circumstances, is her act of belief in a better future. Inspired by interviews with real female prisoners, Masri’s first feature is brave territory: in the war film genre, a female filmmaker has multiple hurdles to overcome.

The Assassin by Hou Hsiao-Hsien, 2015

From the winner of Best Director at this year’s Cannes Film Festival comes The Assassin. Taiwanese maestro Hou Hsiao-Hsien creates a slow feast for the senses very unlike martial arts genre convention. Yet his bold stylistic moves are well matched by his formidable heroine, the lethal assassin Nie Yinniang (Shu Qi). Her true heroism shows when forced to choose between love and duty – but she sure does terrifyingly beautiful things with a dagger in the meantime.

Brooklyn by John Crowley, 2015

A steamliner; the Manhattan skyline; the grainy black-and-white faces of the hopeful and tired – a familiar image of the 20th century American immigrant experience. Brooklyn follows Irish wallflower Eilis Lacey (Saoirse Ronan, a fierce talent to be reckoned with) as she leaves for 1950s New York. Transitioning to American life alone not only brings out the confident woman, but also has her redefining ‘home’ at a time when its stability meant that of women’s place, too. Brooklyn has us celebrating a different kind of strength – a female willingness to try and fail, without ego or comfort zones.