super/collider reports on the deep sea ecosystems of the Pacific Ocean, where strange creatures – including magnetic snails and metal-shell crabs – hint at what life could be like on other worlds

Where on Earth?

In 1977, deep beneath the surface of the vast Pacific Ocean, researchers made an incredible discovery. Using a robotic submersible called Alvin – which would later be used to explore the wreck of the Titanic – they uncovered a previously unknown ecosystem. It would forever change the way we think about life on Earth… and on other worlds.

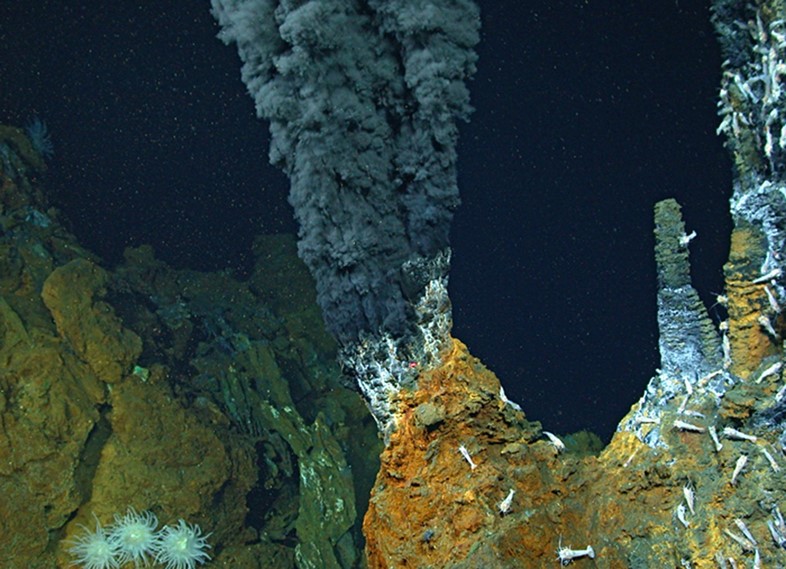

Amid the impenetrable darkness and crushing pressure found at the bottom of the ocean, the eery green video on their monitors showed ghostly crabs, worms, eels and snails living their entire lives around a series of strange towers billowing black smoke from the seafloor. Completely cut off from the sunshine that sustains all other life on Earth, this thriving community of strange creatures must, they reasoned, be getting its energy from somewhere else.

Since that initial discovery, scientists have uncovered similar sites elsewhere in the Pacific as well as in Atlantic, Indian and Caribbean waters. At the heart of each ecosystem is a bubbling hydrothermal vent, where superheated water rich in minerals billows forth from the seabed like smoke from a chimney. Over time, the minerals form deposits that slowly rise like towers from the sea floor, with some reaching 40m high. Around these openings, which release black or white clouds of material depending on their mineral content, a super strange biological community has evolved – one so alien it could help us pinpoint life elsewhere in the Solar System.

What on Earth?

Thriving amid this dark, inhospitable environment is an entire gang of crazy marine life – from shrimps with no eyes to pure white crabs. One of the most mind-blowing is the scaly-foot gastropod, Chrysomallon squamiferum, which incorporates iron into its shell and foot/sucker thing. Like medieval armour, the overlapping plates may help shield the snail against attack by crabs while a unique multilayer shell – also containing metal – prevents them being crushed in their claws. Because of the snails’ iron sulphides and greigite content, the snails are actually magnetic (!) and are being studied by the US military in the hope of developing better defensive armour.

No less extraordinary are the bright red tube worms, Riftia pachyptila, which feed indirectly on the material venting from the seabed. Able to withstand the intense heat and chemistry, they use bacteria in their gut to convert the chemicals into stuff they can eat – a process known as chemosynthesis. Unlike with photosynthesis, in which plants use solar energy as a power source, the worms are able to use the oxidisation of hydrogen sulphide as an energy source and turn sulphur, methane and other inedible substances into food.

The discovery of this process by Dr Colleen Cavanaugh, then a first-year student at Harvard, changed the way we think about how life began on Earth – and how it could thrive on other worlds. Scientists now believe that similar forms of life could potentially exist buried on Mars and on the icy, watery moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

How on Earth?

Haha, good luck getting there – the Moon is probably easier. Dr Cavanaugh, whose discovery has been ranked as one of the 100 most important in the whole history of science, had to wait twelve years to get a spot on Alvin to dive to the seafloor. But whateves, it’s super dark and weird and cold down there anyways.