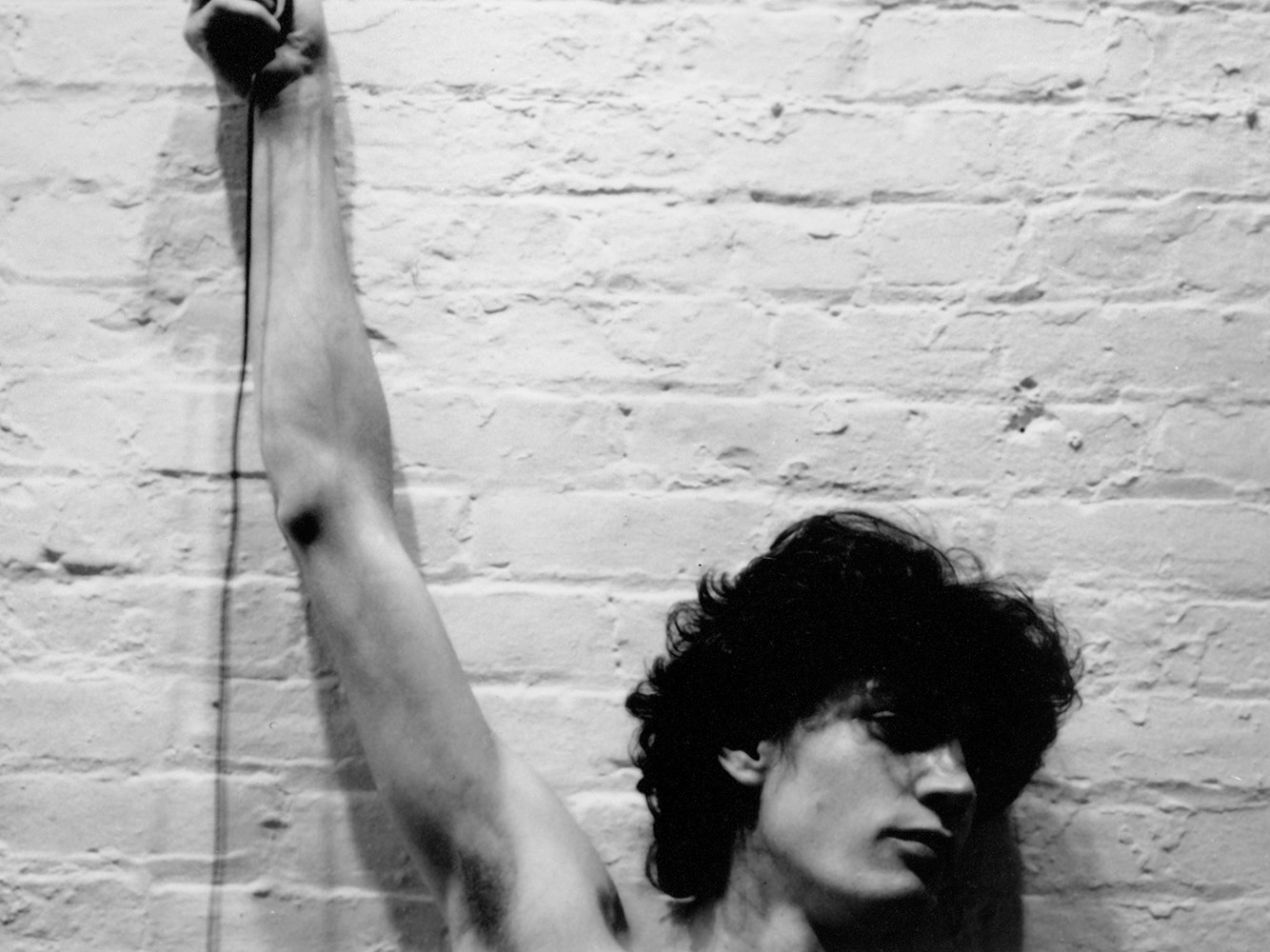

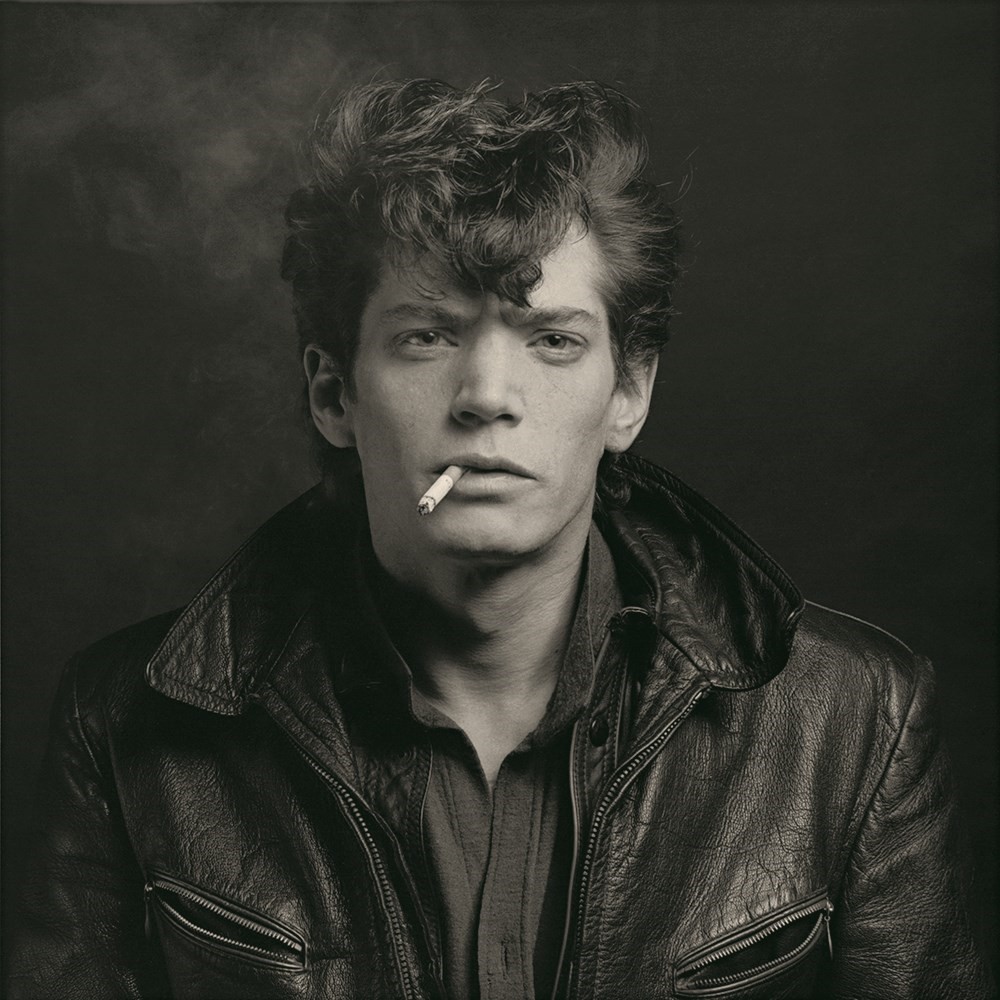

Robert Mapplethorpe passed away on the 9th of March 1989. Yet, having spent the last two-plus years making a film about his life and work, our question is did he ever really die? Since the artist's death, his presence has only grown. This is no accident. It was exactly what Mapplethorpe had intended all along. From the moment he received his death sentence (because that is what a diagnosis with AIDS was back in 1986) he focussed on transcending death altogether.

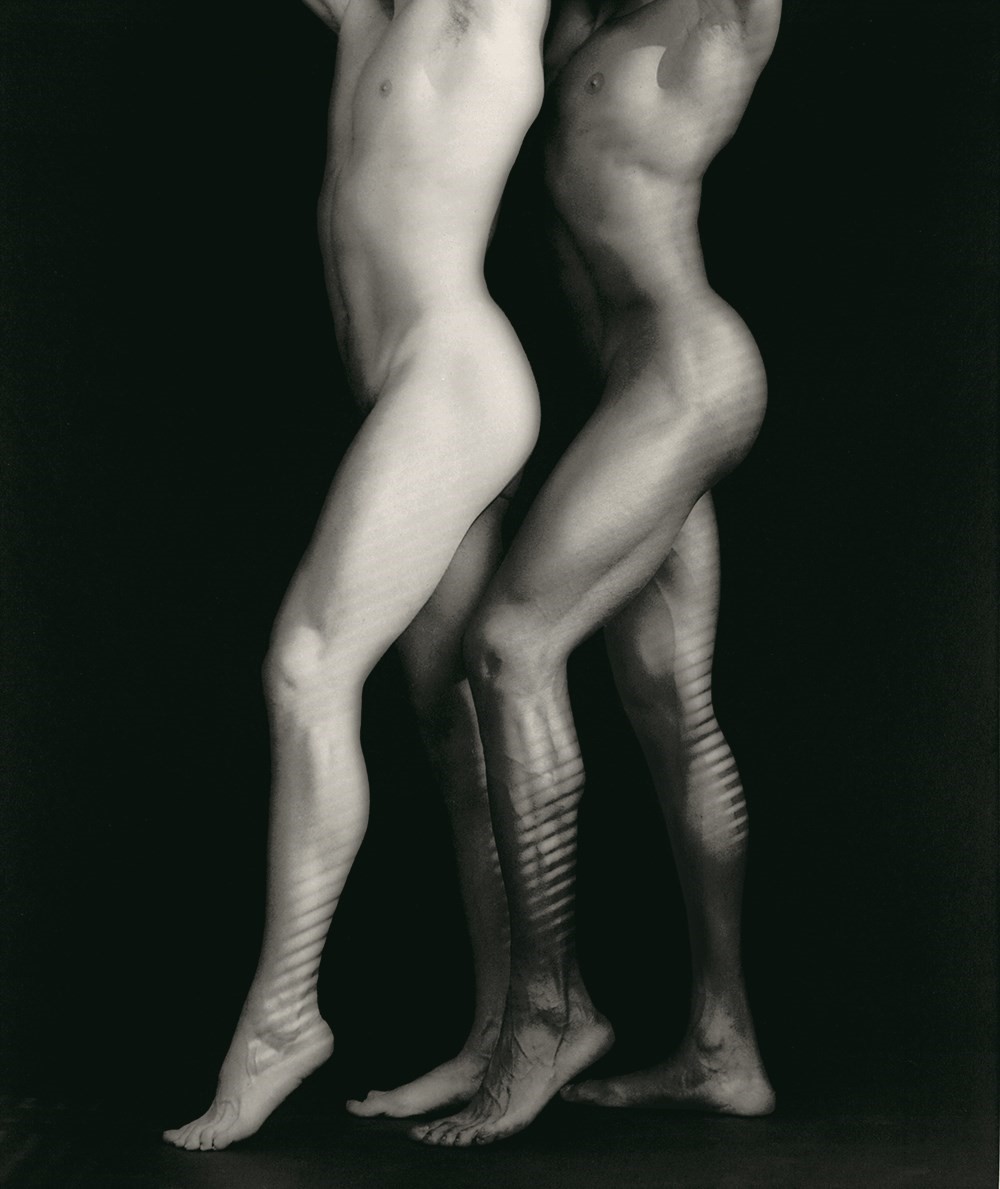

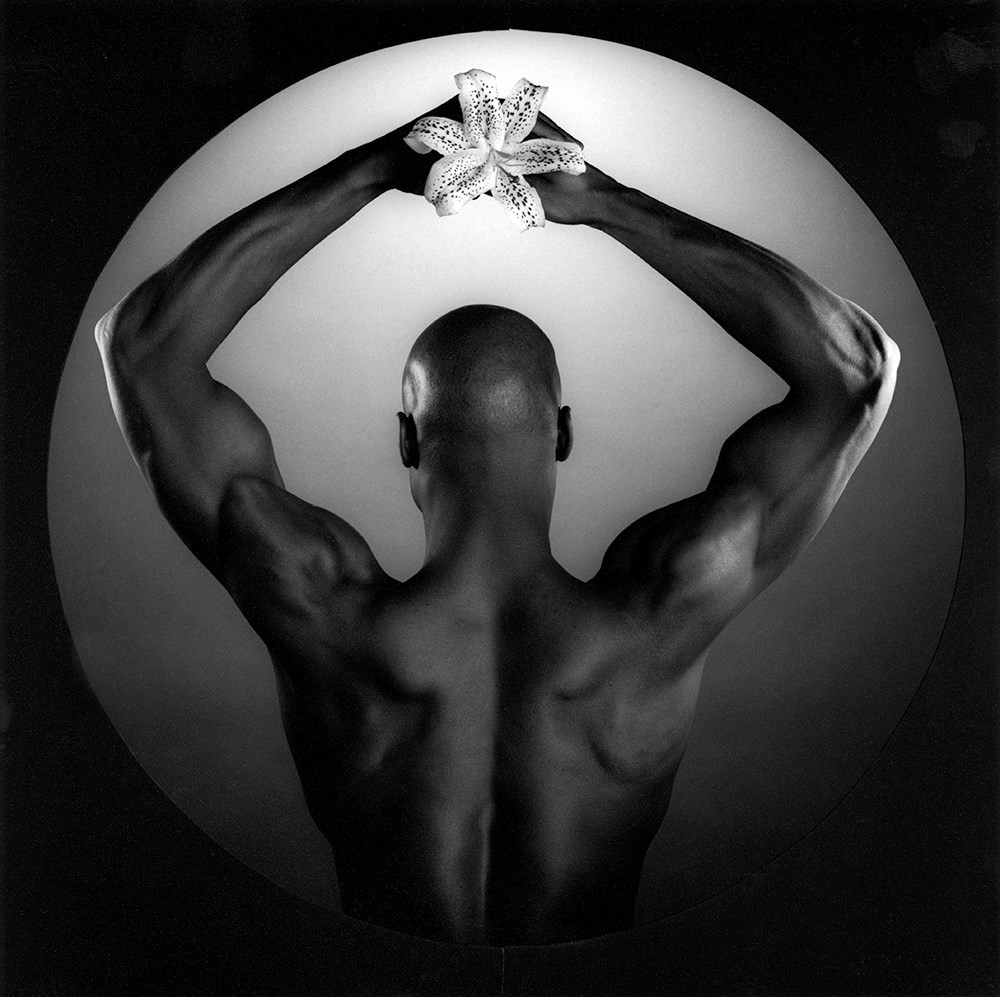

Consider The Perfect Moment, the last show he planned as he was dying. Curator Janet Kardon has never before spoken about the exhibit, but told us – and produced a record of her conversation with Mapplethorpe to prove it – that he wanted to combine the X, Y and Z portfolios together for the first time. “The X portfolio is sex pictures, there’s Y which is flowers, and there’s Z which is blacks,” explained Mapplethorpe to her when they met. “It may be interesting to have a row of X, Y and Z all in one mass, in three rows”. He then designed a “cabinet high enough to prevent a child seeing it but that an adult could look down upon it” she explained.

For most of his career, Mapplethorpe had kept the strands of his work separate. He would show his flowers and celebrity portrait photos in one gallery, his sex pictures in another. “Sometimes I think it's better for the public to be able to separate things because when you mix them all up they just pick the sex pictures out and that becomes the show,” he said. With death just a few months away he combined all of his work, knowing full well that the result would be explosive. And it was. “Just look at the pictures,” spat Senator Jesse Helms. Helms wasn’t talking about orchids, but the enormous black penis on display in Man In Polyester Suit. When The Perfect Moment was put on trial in Cincinnati only a handful of more than a hundred pictures were included as evidence. Just as he had predicted, it was all about the sex.

Mapplethorpe wasn’t political or the least bit interested in freedom of speech, but he knew exactly what these issues could do for him. And indeed the years-long controversy did nothing to resolve people’s squeamishness about sexually explicit art, but it did everything for Mapplethorpe. It made him a household name.

A generation later Mapplethorpe is bigger than ever, whereas other artists working with similar themes in photography have all but been forgotten. Although he has been criticised for it, Mapplethorpe knew that it wasn’t enough to create great work, that work had to be positioned. Fame was the way to outwit, outplay, outlast. It was the way to survive.

For the longest time, Mapplethorpe thought he actually would survive, saved by a miracle cure. The last celebrity portrait he shot was Surgeon General Dr. C Everett Koop. As Jack Walls, his last long term lover explained: “Robert just wanted to find out how he could get better ’cause he thought he was gonna beat this thing.”

Resigned to the inevitable, Mapplethorpe “threw himself a lavish going away party” according to his first boyfriend David Croland. At the event he went on bended knee and asked Robert “What do you want me to do?” Mapplethorpe replied: “Tell her everything”. ‘Her’ was Patricia Morrisroe, the biographer he had charged with writing his biography. “What he meant was ‘keep me alive’,” explained Croland.

This was consistent with his penchant for befriending writers. Victor Bockris. Bob Colacello (editor of Interview), Jack Fritscher (editor of Drummer), Carol Squiers, David Hershkovits (founder of Paper) Ingrid Sischy (contributing editor Vanity Fair) and Susan Sontag. No publication was too small, no intellectual beyond his reach, not necessarily because he liked – or even read – what they wrote. All that mattered was that they wrote about him.

So promiscuous was he in this regard that – thanks to the many interviews he gave his journalist and writer friends – it was possible in making our film to have Mapplethorpe himself tell his story in his own words, and be our narrator.

Another way he plotted to outwit, outplay, outlast was through his Foundation. Set up in 1988 the year before he died Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation’s stated mission was to promote photography as fine art and also fund AIDS research. But above all, it was designed to promote him and his work. Since his death, the Foundation has continued the sale of his work and mounted multiple exhibitions all over the world. “The foundation is essentially operating the business of Robert Mapplethorpe, operating his studio much like he would have if he were alive,” explains Michael Stout, Mapplethorpe’s lawyer and president of the Foundation.

The Foundation is also the architect, the deal granting the Getty and LACMA shared custody of a large volume of his work and his entire archives. It is pure Mapplethorpe; firstly to tweak the East Coast establishment by resettling the work of this quintessential New York artist in Tinseltown, and secondly to divide the work between two museums resulting in not one, but two retrospectives at two of the world’s most prestigious museums.

In the early hours of March 9th, 1989, Jack Walls was sitting by Mapplethorpe's bedside and he decided to head back to his hotel to get some rest. He was about to get into bed when he heard a loud pounding on the door. But, when he answered the door no one was there. Then the phone rang. It was the hospital. Mapplethorpe had just died.

His downstairs neighbour in New York told us a story of also hearing a pounding on her door that night as well. She opened the door and there was Mapplethorpe. “That dream stayed with me for a long time”.

These are all great stories for sure, but as we were filming we began to notice a pattern: Anytime someone was about reveal something truly intimate or possibly unflattering a siren would wail, thunder clap or construction would begin next door. Of course, interruptions are to be expected whenever you are on location, but when we interviewed Edward Mapplethorpe, Robert’s brother who worked closely with him for many, many years, it was almost impossible. Every thirty seconds there would be some interruption.

“You know what this is, don’t you?” Edward asked us with a big smile. “It’s Robert. He’s always doing this to me”.

Days before our world premiere of Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures at the Sundance film festival, we sat Edward down in a conference room and showed him the film. Sure enough at the most critical point, the phone rang but no-one was there. Edward thought differently. “Hello, from the other side”.

We reassured ourselves we were making a documentary, not a ghost story. But perhaps we were making both. Mapplethorpe said that the life he was leading was more important than the pictures he was taking. In other words, he was a documentary artist who used the pictures he captured and the writers he collected as a means to record his ultimate work of art, himself.

Our film, then, can be seen as a continuation of this work with Mapplethorpe himself as our revenant-like producer. Because until it was suggested to us, it never occurred to us to make a film about his life, and we were even reluctant at first. Projects like this can often take years to set up, but this had a life of its own and came together very quickly; HBO, the Foundation, LACMA, Getty, and almost all our subjects were eager to participate from the outset (after all Mapplethorpe had instructed them to tell his story – even Patti Smith says she wrote ‘Just Kids’ in fulfillment of a deathbed promise to Robert).

In the same way that he planned his last show, The Perfect Moment, perhaps Mapplethorpe had also planned this. He knew it would take years for the dust to settle after all the fuss before we could look at the pictures again the way he intended us to. So Mapplethorpe has just been biding his time until now, waiting for the perfect moment to represent himself. A quarter century after his death, the artist is present and more alive than ever.

Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures is released in cinemas across the UK from April 22, 2016.