In part one of our interview, Linda Rosenkrantz, author of Talk, discussed past friendships and the maddening din of psychoanalysis jargon that defined the 1960s. In part two, she opens up about the mixed response to her often painfully honest novel and responding to an emerging tradition of Pop Art.

NO: You run a baby-naming website now. How did that come about?

LR: The baby-naming thing is taking over my life. I’ve always been fascinated by names. At one point I was going to write an article about it. I had a friend who was an editor at Glamour magazine who thought it could be a good idea for a book and offered to collaborate with me on it. And so we wrote this first book called Beyond Jennifer and Jason which sort of revolutionised baby naming. It got a lot of press, was a best-seller and led to us writing nine more books, Jewish Baby Naming, British Baby Naming, blah blah blah. Then by 2008, we had luckily retained the media rights, and were able to publish this huge database of names online, and it’s just become huge. It’s totally taken over my life. We get 6 million unique hits a month.

NO: That’s a big departure from Talk.

LR: Before Beyond Jennifer and Jason, all baby naming books just provided the etymology. But we approached it in a totally different kind of way. We looked at the social meaning of names, the reverberations, the imagery, trends, which had never been done before. Now a lot of people are doing it.

NO: That’s cool.

LR: It’s very time-consuming, though. I do it seven days a week.

NO: Was it difficult going from doing that to having to wear your author hat again?

LR: Well I’ve written non-fiction books in between. I wrote a social history of Hollywood with my husband and did a memoir and a history of telegrams. But no fiction was published in the interim.

NO: Is your husband in the book?

LR: No I hadn’t met him then.

NO: Is he anything like the guys in the book?

LR: No, the opposite! He’s sane and nice. He’s a Brit. I met him through a mutual friend. I was editing a magazine called Auction at the time for Sotheby’s and he was recommended to write for the magazine. Today is our wedding anniversary.

NO: Congratulations.

LR: [Feigns British accent] Well thank you! 45 years.

NO: Oh so you met quite soon after Talk?

LR: Yes. You know, all these numbers are horrifying to me.

NO: Do you identify with the version of yourself presented in the book? Do you recognise yourself or does it seem like a completely different person?

LR: Not completely different. The humour’s the same. There are a few passages I still find hard to read. That’s been the thread throughout. The first time it came out I was terrified about the reactions of the people at Sotheby’s, and my family.

NO: How did they respond?

LR: Well my mother immediately went into therapy. [Laughs] My father never read it. He carried it around and showed people the picture of me on the back: "look my daughter wrote a book." Never cracked it open though. Even when his friends said, "do you know what this book is about?" He just shook his head. "Nope!" And actually the president of Sotheby’s New York asked if he could buy the original manuscript. And now I’m worried that my younger audience of baby-namers are making the connection. But I don’t think there’s much crossover.

NO: Do you have kids?

LR: I have one daughter.

NO: Has she read it?

LR: Oh yeah she’s a fan. But she’s very much a grown up. But the reaction to it was so mixed the first time around. It got a lot of negative press. People were angry. Kerouac was just typing and this person was just taping. They didn’t know what to make of it. But, on the other hand, it got some great reviews. British Vogue picked it as one of its books of the year. It had some fans. Leonard Cohen wrote. Harold Pinter wrote to someone I know about it saying how much he enjoyed it.

NO: It reads a lot like Pinter.

LR: Yeah. You can see why he would like it.

NO: And maybe it was always going to take a while, because it is – it’s such a cliché – but it is ahead of its time.

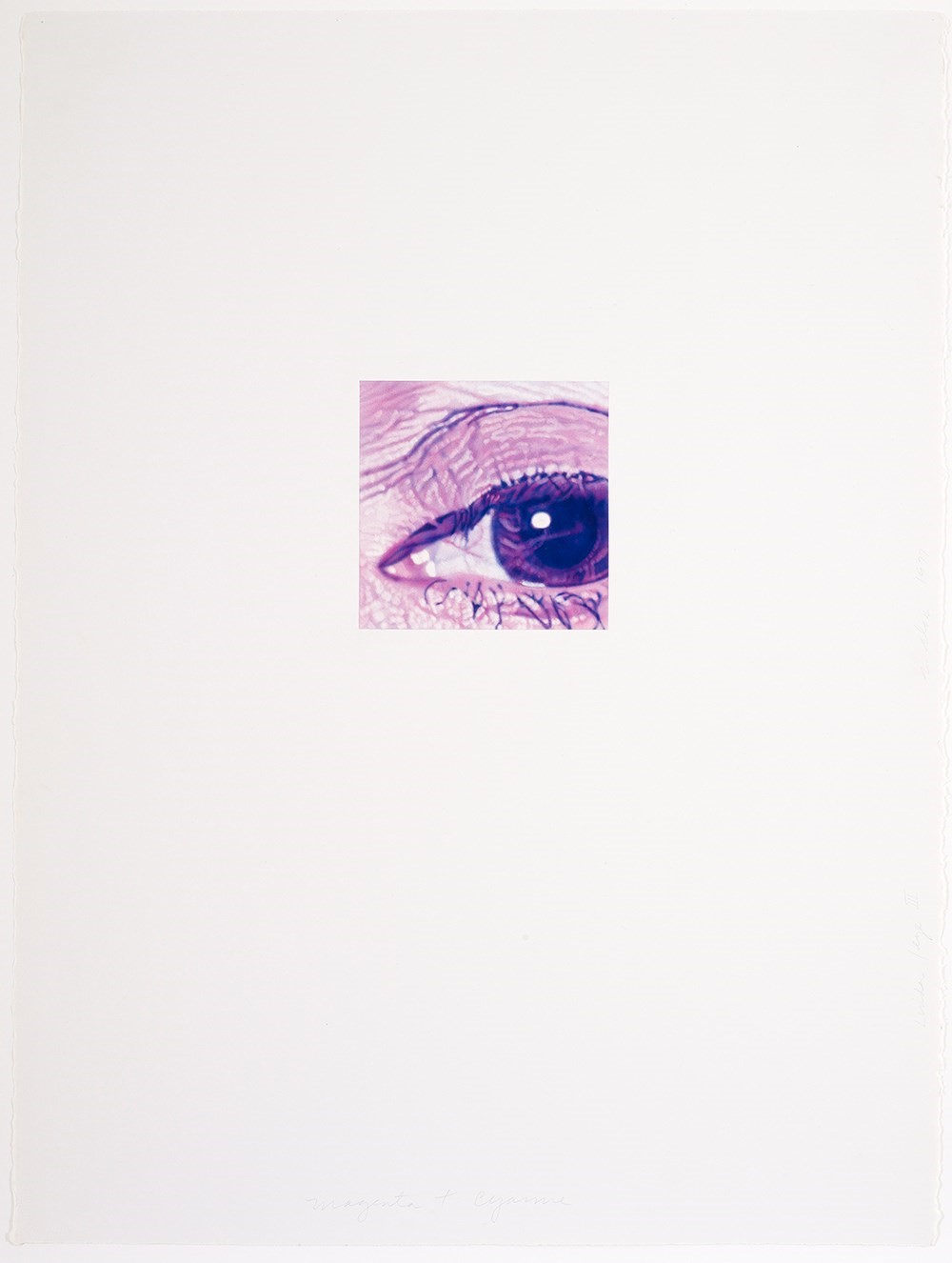

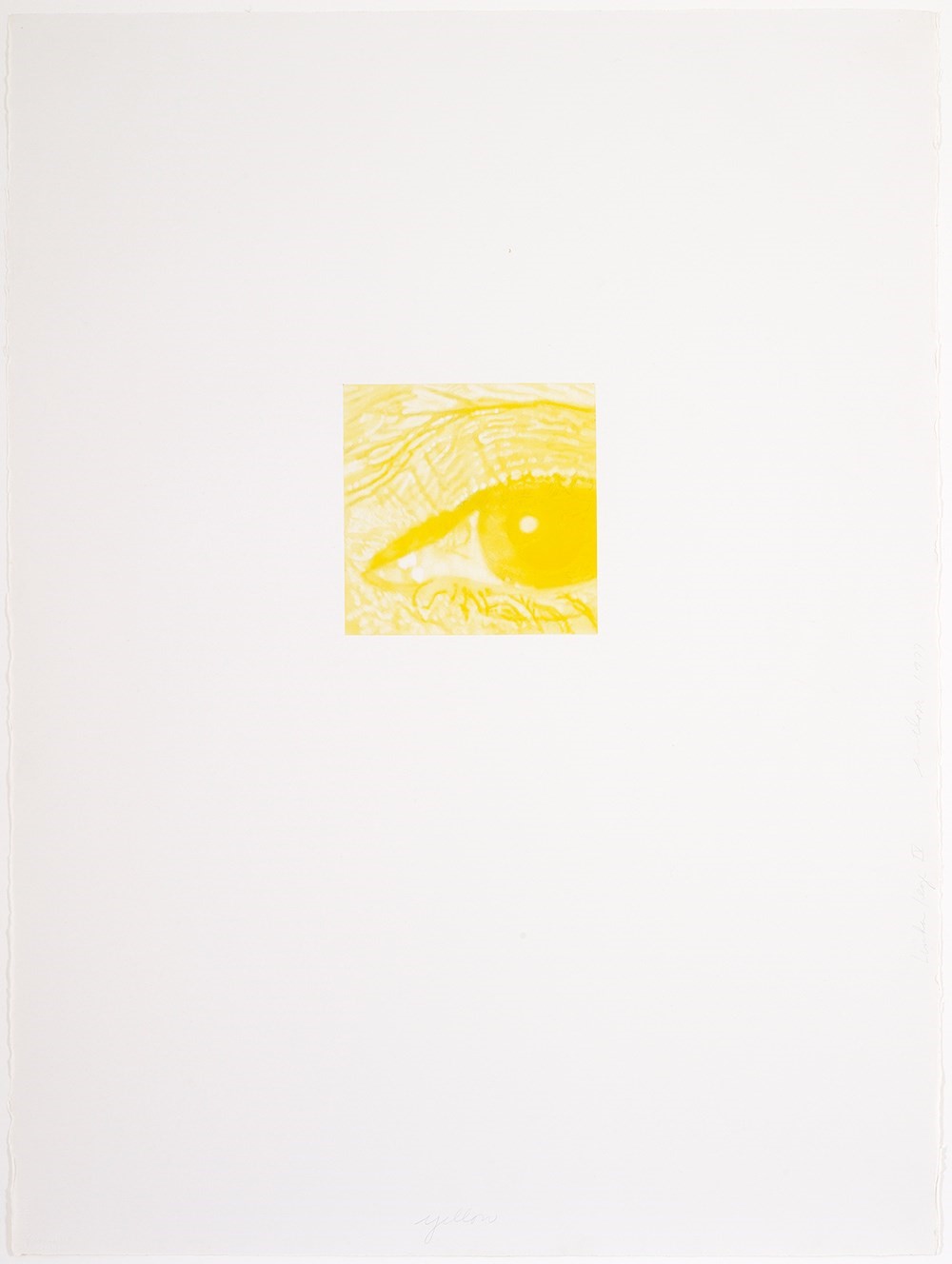

LR: Yes but it came out of the milieu of the sixties. Realistic documentaries were being made by the Maysles brothers. I talked to Albert Maysles when he was just making his first film Salesman and we were talking about what we had in common. Pop art was popping and Talk came out of all of that.

NO: Weren’t you terrified of exposing yourself? And because the reception was so mixed, did you take the negative press badly?

LR: No. I really didn’t. I almost took it humorously. For instance, there was a court in New Zealand that tried to get it banned from libraries because it was so ‘shocking’. I found that kind of funny.

* Check back next week for the final instalment of Nathalie Olah's conversation with Linda Rosenkrantz.