When Pedro Almodóvar discovered Rossy de Palma amid the anarchic nightlife of early 80s Madrid, he found a mischievous accomplice and cinematic muse. Over coffee and tapas, she chronicles the decadent era of La Movida Madrileña

Madrid’s tangerine skyline at sunset, its neon-soaked Gran Vía or the sprawling jumble of El Rastro flea market belong as indelibly to Pedro Almodóvar as the Brooklyn Bridge to Woody Allen. The city has frequently played a frenetic, slightly insalubrious supporting role to Almodóvar’s other muses: a close-knit clan of “actores amigos” from Carmen Maura to Penelope Cruz, who repeatedly flesh out the strong, exuberant females he puts centre-stage.

One of Almodóvar’s longest cinematic affairs has been with statuesque actress Rossy de Palma, whose unmistakable, Cubist profile has earned her the nickname “Dama Picasso”. Their collaboration has lasted 30 years, from the unhinged erotic thriller of 1987, Law of Desire, to Almodóvar’s new drama, Julieta. When we meet at an Art Deco café on a washed blue Madrid afternoon, the actress has just returned from the shoot in a rocky coastal village in northern Spain: “It already smells like a masterpiece!” she declares, sipping coffee as assorted dishes of tapas are placed before us. “I play a very mean old woman,” she laughs. “I’m not beautiful in it at all, I have to tell you!”

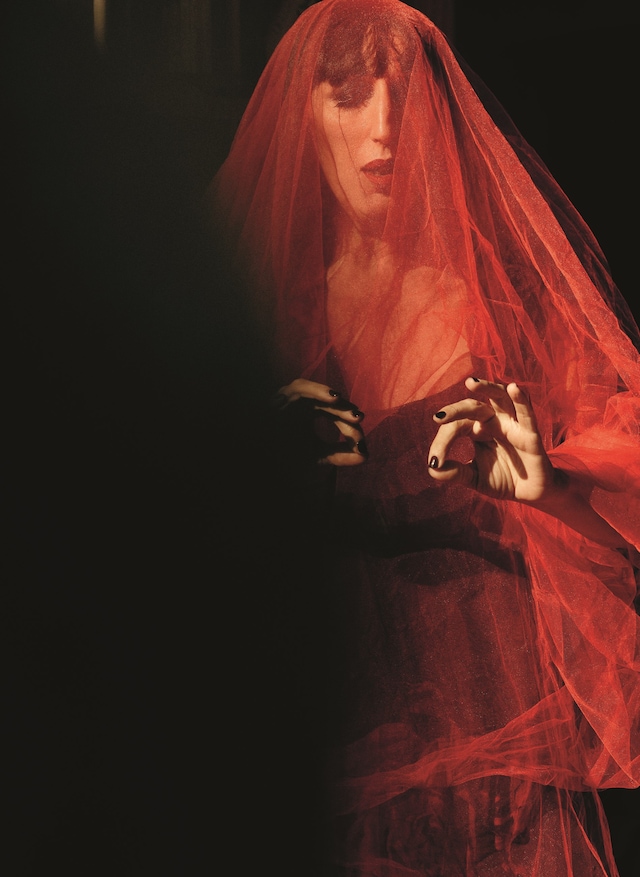

De Palma’s extraordinary features, framed by vinyl-black hair, instantly conjure Almodóvar’s uniquely off-kilter world of hyperreal emotions, sly mischief and sensual visuals, to which the actress has brought some effervescent comedy turns. From the teenage virgin who accidentally swallows sleeping pill-laced gazpacho in Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, to the moped-riding drug dealer who gives Antonio Banderas a brutal kicking in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! or the lesbian maid in Kika, she has gleefully accepted Almodóvar’s every challenge: “I love Pedro. He is family,” she says. “He is my cinematographic father.”

De Palma’s unorthodox trajectory can be traced back to one Halloween night in 1983 in her hometown of Palma, Mallorca, when Rosa Elena García Echave, 19, and a handful of friends formed a band, Peor Imposible (“Worst Possible”, in reference to their musical abilities) and performed at a local gallery, mixing Klaus Nomi-style theatricality with ebullient pop. Dressing variously as clown-jesters or in rainbow beachwear, by the summer of 1984 they had expanded to nine members and were riding the wave of a synth-drenched hit, Susurrando, with de Palma responsible for vocals, beatbox and the odd provocative act: “Two girls kissing each other, at that time it was a scandal!” she laughs, referencing one of the group’s irreverent and cherishably lo-fi videos. “My mother was shocked. She said, ‘Everybody is talking about you in the local shop!’”

In the early Eighties there was only one destination for rebellious Spanish youth: following Franco’s death in 1975, Madrid had morphed from black and white into DayGlo. All but mothballed during the dictator’s 39-year reign, the capital was making up for lost time. What began as a spontaneous, cathartic, 24-hour street party opened the floodgates and La Movida Madrileña was born: a hedonistic, amorphous cultural movement with Madrid as its electrifying nerve centre. “We came here with no money, but it was no problem,” she remembers. “It was a completely unconsidered explosion of creativity. It was hard, too. Many I knew fell into drugs. A lot of people died of AIDS, or overdoses. It was decadent but very rich in creativity.”

She plunged into a riotous circle of artists, photographers, filmmakers and musicians inspired by punk and New Wave, who were openly challenging the sacred Spanish institutions of religion and family and pushing the limits of sexuality, with a newly-liberated media and proliferation of DIY ’zines documenting their exploits. “The heart of the city throbbed in time to some kind of infinite energy,” wrote Bob Spitz, reporting for Rolling Stone. Even Warhol anointed the scene with his presence in 1983, and was introduced to La Movida’s unofficial ringleader, a young filmmaker who also strutted the stage in fishnets, heels and crimson lipstick as one-half of punk-rock duo Almodóvar & McNamara. Drawing on influences ranging from Latin American telenovelas to Douglas Sirk melodrama, Almodóvar’s hyperactive early films, with their amphetamine-paced plots and underworld characters, reflected the messy anarchy of the time – his cult 1980 film, Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas del montón, features a particularly memorable urination scene, and Almodóvar himself as the judge of an erection contest.

De Palma’s cameo as a television presenter in Law of Desire, reveals her style exactly as it was then: enormous pink plastic hooped earrings, stripes of pink across her eyelids, and a black mane hairsprayed into a towering quiff. Almodóvar immediately cast her again, and when Women on the Verge… became an international hit, it was the fashion world’s turn to be bewitched. If she had found an eccentric, shifting family amid Almodóvar’s troupe, her unconventional beauty found its expression in fashion. Herb Ritts shot her in Hollywood, she modeled for Thierry Mugler, George Michael invited her into his Too Funky video, and while she was in Paris walking for Jean Paul Gaultier, she was introduced to maverick director Robert Altman, who promptly cast her in Prêt à Porter, his satirical 1994 tale of sex, greed and murder at fashion week. “I think Rossy is capable of doing anything,” Altman said. “I can’t take my eyes off her.” Gaultier went on to design her costumes for Almodóvar’s subversive, kitschy Kika, and their friendship has endured; de Palma was on the catwalk for the designer’s final show last year, ripping off an hourglass suit to flaunt her corset and stride the stage to Ru Paul’s Supermodel. If the wild days of La Movida are long past, its spirit is clearly still alive in de Palma. “Beauty is audacity,” she says simply. “It is not asking anyone for permission to be yourself.”

She elaborates on her philosophy in a new Surrealist one-woman show, currently in rehearsals at Madrid’s Teatro Español (adjacent to one of Hemingway’s favourite aperitif haunts, it’s the city’s oldest theatre). Clad in typically flamboyant de Palma-designed gowns, including headgear made of breadsticks and onions, she says in its monologue: “I have felt alone, unique, like an anachronism, an error. Poetry, Dadaism, Surrealism… they comforted me when facing adversity.”

These days, the director who discovered de Palma amid the turbulent days of La Movida is an Oscar-winning Spanish national treasure, his vertical shock of hair turned white, while his longtime muse is a bona fide style icon who served on the jury of Cannes last year. But the irreverent, untamed movement that brought them together 30 years ago continues to inform their work: “Pedro is so revered now, sometimes actors feel the pressure of not wanting to disappoint. But with him I feel free to play and enjoy. He knows that the accidents that happen on set give so much richness,” the actress says. “You can always be young if you remain curious. Now I’m 51, but the older I get the more joy I have, the more connection I feel with the little girl that was surprised by everything.”

This article originally appears in the Spring/Summer 2016 issue of AnOther Magazine.

Pedro Almodóvar's upcoming movie 'Julieta' is released nationwide on August 26, 2016.

Hair and make-up artist: Kley Kafe at Cool using Estée Lauder and Kérastase; Styling assistant: Katie McGoldrick.