As a new exhibition of his bright, optimistic designs opens at London's Fashion and Textile Museum, we examine the extent of his prolific practice

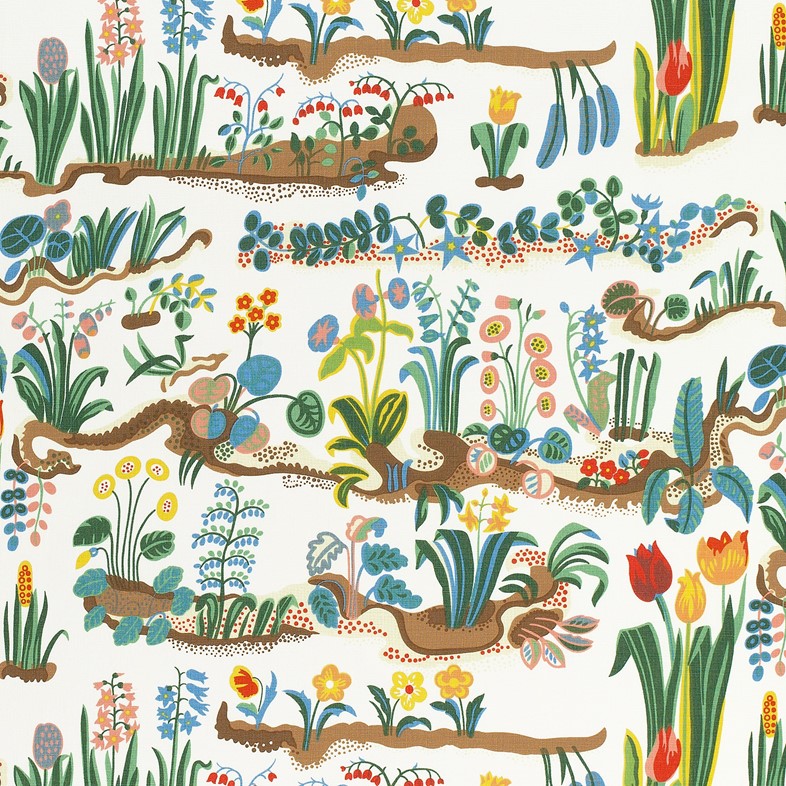

Who? “Josef Frank is always an interesting subject for an exhibition,” Maria Wiberg, curator of Stockholm’s Millesgården tells AnOther. “He was a multitalented artist and played a special role in Sweden’s design history. Personally, I really like the pictures in some of his fabrics, for example in Hawaii, where you really can feel how the plants are growing, or in Vegetable Tree, which is a very beautiful picture of how different fruits can grow together on the same branches, as we hope people from different parts of the world cope with each other and live together.”

Multitalented by way of his many pursuits, Frank was an architect, an artist, a designer, and at the age of 48, an immigrant in Stockholm, the result of increased Nazi persecution against Jewish people in his native Austria circa 1933. In the decade previous he’d been part of the remedy to Vienna’s housing crisis, designing estates and large residential blocks, while in 1925 he co-founded the interior practice Haus & Garden alongside architects, Oskar Wlach and Walther Sobotka.

In Sweden he joined Estrid Ericson’s design company Svenskt Tenn, a collaboration which would, three years later at the 1937 World Expositions in Paris, produce a major professional breakthrough for the pair – such was the fresh appeal and contradictory nature of the display the company presented – and the prototype for ‘Swedish Modern’. Later, in 1939, he acquired Swedish citizenship, where he remained until his death in 1967, following his return from the States in the mid-1940’s (he and his wife Anna had fled to New York following the outbreak of World War Two).

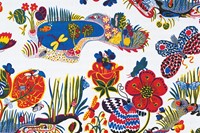

What? While Frank’s output at Svenskt Tenn included furniture, glassware and lighting – the company today retains 2,000 of his furniture sketches – his interior designs were perhaps his most prominent triumph. Somewhere between William Kilburn, William Morris and Marikmekko, both in the timeline of design and aesthetically speaking, his textile pieces explored colour, pattern and botanical imagery with a considerable awareness.

“It was seeing it in the context of the Svenkst Tenn store on the Strandvagen in Stockholm that really opened my eyes to the power and positivity of Frank’s work,” says the Fashion and Textile Museum’s curator, Dennis Nothdruft. “His ideas of interior decoration – that the things you love will all work together in a room – remain important messages for modern life. Indeed, it is as relevant and as liveable today as it was when he was designing them.”

The recurrent focus of his prints, the natural world, did much to emphasise his stance on the idea of creating space within one’s home, employing the eye to encourage this notion through his use of pattern. “The monochromatic surface appears uneasy, while prints are calming and the observer is unwillingly influenced by an underlying slow approach,” said Frank. “This richness of decoration cannot be fathomed so quickly, in contrast to the monochromatic surface which doesn’t invite any further interest and therefore one is immediately finished with it.” Elsewhere in an article published in an 1958 issue of Form magazine, he remarked that, “Anything that is in your taste will automatically fuse to form an entire relaxing environment. A home does not need to be planned down to the smallest detail or contrived: it should be an amalgamation of the things that its owner loves and feels at home with.”

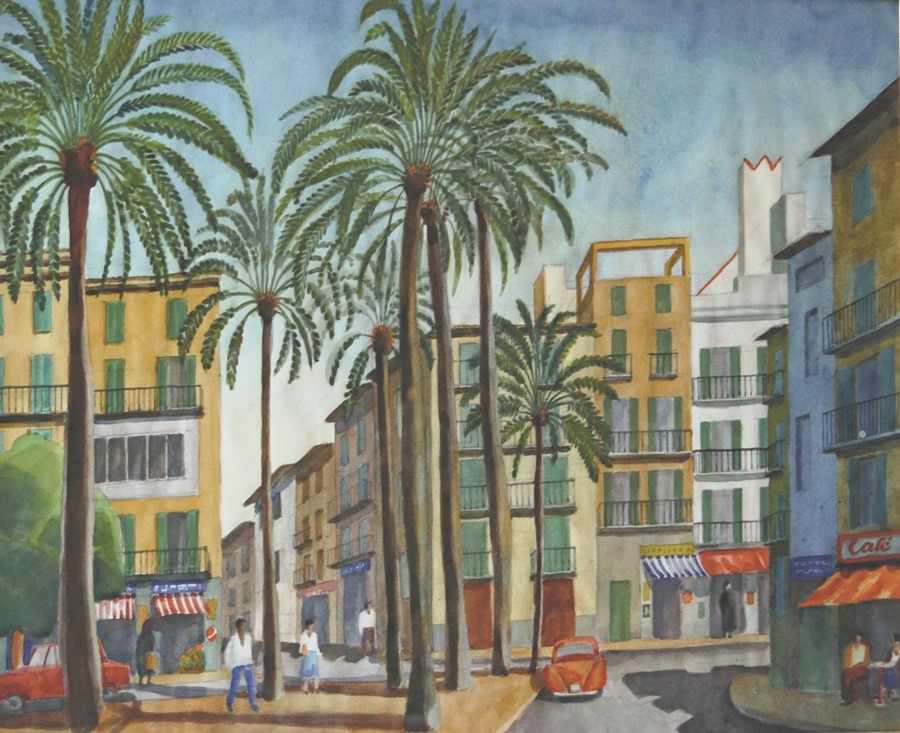

Why? For the first time ever, an exhibition of Josef Frank textiles will open in the UK this Friday. Curated by Wiberg together with Anna Sievert and Ulrica von Schwerin Sievert, who authored Josef Frank: The Unknown Watercolours, the show at Bermondsey’s similarly bold Fashion and Textile Museum will explore Swedish home staples such as Frank’s textile furniture and rug designs, alongside the less studied parts of his portfolio; a series of watercolours. “The starting point [for the exhibition] was the opportunity to show an unknown part of the creative life of Josef Frank,” notes Maria of the paintings. “A gentlemanly pursuit that became a creative outlet for Frank,” adds Nothdruft, “The echoes of the textile patterns are in these watercolours, but they also stand in contrast to the bold colour and scale of his printed textiles.”

“This is a great time for a Frank exhibition,” he continues, “his work has an optimism and hopefulness, a positivity and vibrancy that we all need in today’s world.”

Josef Frank: Patterns – Paintings – Furniture runs until May 7, 2017 at the Fashion and Textile Museum, London.