In 1965, Grey Villet documented the powerful story of Richard and Mildred Loving – an interracial couple fighting for the right to love. Here we meet his wife, Barbara, to discuss a newly released book of the beautiful images

In early 1965, Life photographer Grey Villet set off from his New York home and headed for rural Virginia on a covert commission. He was going to photograph Richard and Mildred Loving, a working-class, interracial couple who were living in hiding with their three young children in an isolated farmhouse in King and Queen County. The Lovings were in the midst of a groundbreaking court case against the state of Virginia, which seven years earlier had proclaimed their marriage, in the state of Washington, illegal according to Virginia’s miscegenation laws. They were cast out of the state – leaving behind their family, friends and contented country life – and banned from returning for 25 years.

The pair had temporarily relocated to a D.C. ghetto, but with Richard out working all day as a laborer, and her children forced to play in the dangerous city streets, Mildred had finally snapped and sent a letter about their predicament to Bobby Kennedy. Kennedy referred the Lovings to the American Civil Liberties Union, thus setting the wheels in motion for what would prove a vital milestone in civil rights history. Two years after Villet shot the pair, they would win their case at the US Supreme Court, and finally see mixed-raced marriage legalised in Virginia, but when the photographer first met them on a mild spring day, they were twitchy, frustrated and tired of living in secrecy – but, most noticeably of all, they were deeply in love.

Villet’s resulting photographs, taken over a two week period and featuring the couple relaxing at home with their kids, visiting their lawyers and attending a drag race, were the driving inspiration behind Loving, the new film from American director Jeff Nichols, starring Joel Edgerton as the tough but gentle Richard and a breathtaking Ruth Negga as the determined, modest Mildred. “There’s one photograph – the one of Richard with his head in Mildred’s lap – that Jeff told me had absolutely spoken to him,” explains Barbara Villet, Grey’s widow and former Life editor, on the phone from New York. “He said he saw the picture and thought, ‘I have to do this movie,’ because it’s all there. It’s all in the trust; it’s all in the ease between this man and this woman; it’s all about love and about how the photographer understood it all. He said that without Grey’s work he couldn’t have made this film.”

Villet’s visit to Virginia, and the moment he captured that iconic image, both feature in the film, the tall, discreet photographer portrayed by a lolloping Michael Shannon. “He’s very good; he looked a lot like Grey and he almost had his walk,” Villet says of Shannon’s performance. “But he made one grave error,” she adds in a hushed tone. “When he takes the picture of them on the couch, he holds the camera down at waist-height, surreptitiously, so as not to disturb them. The message is that Grey laboured not to disturb his subject, which is true, but Grey would have never put the camera down. He would have shot it in a single lens reflex – he watched everything he did right through the lens. And if they’d asked me, I would have told them: he’d have been lying on the floor!”

Villet is intrinsically acquainted with her husband’s style and approach, the pair having co-conceived myriad projects for Life over the course of their happy marriage, and Villet having spent many years since Grey’s death in 2000 overseeing his extensive archive and poring over his negatives for various exhibitions and publications of his work. The pair first met when Barbara commissioned Grey to shoot a feature she was producing for Life, called The Lash of Success, which centred on a businessman whose quest for financial gain had resulted in a burgeoning lack of humanity. Their first encounter took place in an LA hotel, where the South Africa-born Grey, who stood at 6 foot 4 inches to Barbara’s 5 foot 2, teased the young New Yorker by ordering her a double Martini (the stereotypical New York drink of choice) and himself a pot of tea. The couple forged an instant connection, underscored by a mutual sense of compassion and interest in “the commonplace”: the idea that everybody has a story, Villet explains. “The first evening he asked me to marry him,” she laughs, “and two days later I said yes.”

Villet was not involved in the Loving story, having given birth just two weeks earlier, but she has since come to know Grey’s photographs of the Lovings inside out, her latest endeavour a newly published photo book of the series, for which she has scribed the accompanying text. “He was the perfect person for this story because he didn’t pose things,” she observes. “He waited and he watched, and as far as his subjects were concerned, he simply disappeared; it was uncanny, people stopped noticing him. He was like a visual spy, but a compassionate one. He had the most unbelievable capacity to understand people, to look into their hearts and souls and get to the core.”

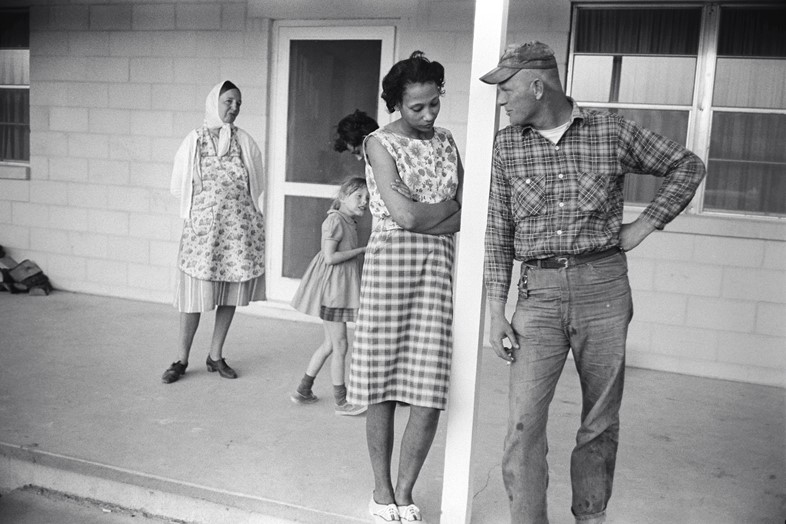

These traits are all strikingly apparent as you leaf through the pages of the book, aptly titled The Lovings: An Intimate Portrait. We see Mildred and Richard sweetly embracing, worriedly discussing, softly kissing, busily engaging in family life, always seemingly unaware of the photographer’s presence, even when the images are captured in close-up. “When I look at contacts or the negatives in order, I can see Grey moving in,” Villet says. “He’s sensing that something’s about to happen, and then in the next sheet, he’s in there: he’s seen it, moved towards it, isolated it, changed lenses in a fraction of a second – his technical ability was amazing – and then he’s got it!” One such example sees the couple standing on their front porch, a white wooden post symbolically standing between them. In the first shot they chat casually, Richard’s mother and two of the children visible in the background. In the next, Villet has intuitively zoomed in on the pair, capturing the exchange of a beautifully tender, highly intimate glance.

Perhaps the most poignant thing that Villet’s images, and Nichols’ film in turn, illustrate is the fact that the Lovings were, in Barbara’s words, “a quintessentially ordinary couple extraordinarily in love with each other”. They never saw themselves as civil rights activists, they simply wished for the basic right to live and love wherever and whoever they chose. As Richard said in the Life feature, “We have thought about other people, but we are not doing it just because somebody had to do it and we wanted to be the ones, we are doing it for us.”

Villet’s photographs stand as an indelible testament to this mutual devotion and the wonderful changes it gave way to. Indeed, a set of 50 beautiful prints, which Villet had had processed in the Life lab and hand-posted to the Lovings himself in 1966, were treasured by the widowed Mildred in her later years, according to her daughter Peggy. All of these feature in the book, the first publication of the entire photo essay, which finishes with a rare statement given by Mildred, the year before her death, in support of marriage equality. “I am proud that Richard’s and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That’s what Loving and loving are all about.”

The Lovings: An Intimate Portrait is out February 14, 2017, published by Princeton Architectural Press.