We meet American filmmaker Kelly Reichardt to discuss her new film, a masterful ode to ordinary life in America’s north-west

A few years ago, American filmmaker Kelly Reichardt stumbled across a story by US author Maile Meloy. She was captivated, and immediately purchased the writer’s two collections of short stories, Half in Love (2002) and Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It (2009). In Meloy’s Montana-based prose, Reichardt found all of the ingredients she looks for in a narrative. “They had really strong characters,” she tells AnOther, on the phone from New York. “They introduced a new American landscape that I was interested in checking out; I wanted to do something outside of Oregon [where her last four films were shot]. They also included a lot of detail, particularly about the processes of work and chores – the small strokes of life that I find interesting.” After finishing the books, the filmmaker contacted Meloy to gain her permission to use some of the stories for the basis of a film. She then spent “the better part of year trying to figure out which ones could work together and how” before finally completing her script. The result is Reichardt’s spellbinding sixth feature film, Certain Women, which arrives in UK cinemas today, featuring a stellar cast including Laura Dern, Kristen Stewart and Michelle Williams, the star of Reichardt’s 2008 movie, Wendy and Lucy.

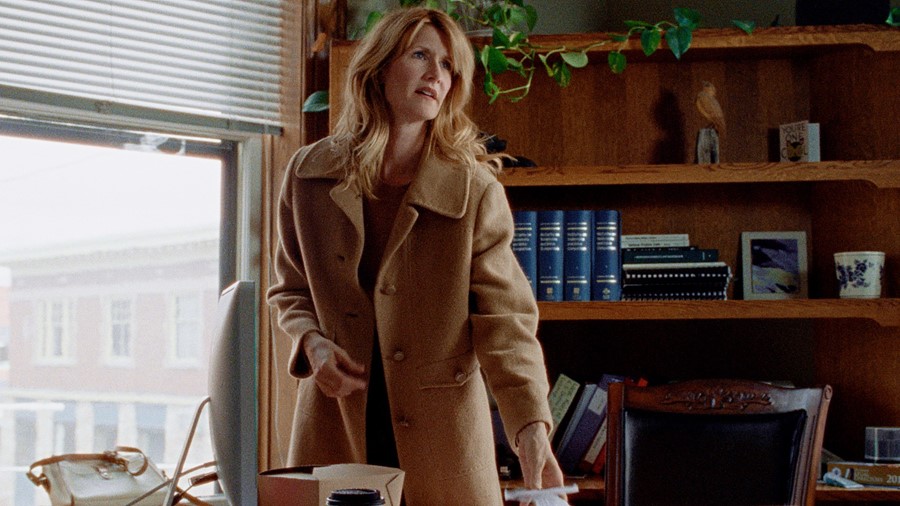

Like Reichardt’s other films, and indeed Meloy’s writing, Certain Women is an investigation into the in-between moments that form much of the fabric of human existence. In her worlds, actions speak a thousand words, while dialogue is sparse. The film presents us with a triptych of vignettes, played out one after the other, each set under the vast, visually arresting Montana skies. The first introduces us to Laura Wells (Dern), a lawyer battling the inherent sexism of her field as well as her moral conscience when one of her clients, a working-class labourer injured on the job, finds his case crushed by a loophole in the system. The second sees Michelle Williams step quietly into the spotlight as Gina, a frustrated wife and mother pursuing her dream of building an idyllic country cabin from locally sourced materials with a steely determination. The final segment follows a lonely ranch hand, exquisitely portrayed by newcomer Lily Gladstone, as she accidentally wanders into an educational law class conducted by weary law student, Beth (Stewart). In a handful of afterclass dinners, the pair seek solace in companionship to differing degrees of intensity. The three stories are very loosely threaded by an overlap of characters, but the unifying link is the strong-willed female protagonists, the so-called “certain women”, each searching for something undefinable just beyond their grasp.

The Montana landscape is worthy of a cast credit all of its own, its wide-open expanses beguilingly captured on 16mm film by cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt. When scripting the movie, Reichardt spent days at a time in the western state, soaking up its character and that of its inhabitants. “I took a lot of pictures of people and began my casting process by first imagining actual, non-actors in that world,” she explains. “Regions have their own tones, their own ways and pace, and I needed to understand that.” The film’s distinct, melancholy aesthetic, rendered in dreamy, muted hues, was the product of similarly thorough research, Reichardt turning to “various painters” to inspire the costume and production design. “We worked off Milton Avery’s abstract paintings to pick the colours for each of the stories,” she expands. “And some of Alice Neel’s paintings for colours, posturing and set design.”

When it came to the rehearsal process, however, the director put her faith firmly in the hands of her cast. “For the most part the actors flew in the day before shooting,” she explains. “Kristen and Lily came a little early to take horseback riding lessons and Michelle, James LeGros, who plays her husband, and I spent a day in their characters’ tent, just figuring out the family situation. But we didn’t hammer it out too much. I tend to figure things out as I go, just as I do in the editing room [Reichardt edits all of her films herself]. The story’s not a mandate at the beginning; it’s more that it finds its way.” This intuitive approach, as Kristen Stewart pointed out in a recent interview with Variety, is what makes the director such an unusual and inspiring person to work with: “If you’re ever trying to tell the story too much [Kelly’s] just like, Chill, it’ll find itself. Whatever’s worth it will rise… That’s why her films are so drifty and natural and alive.”

However, Reichardt has had a notoriously difficult time convincing the film industry of the merits of her methods, frequently expressing her frustration at the fact that female directors with an offbeat manner of filmmaking have to fight to the death to get their movies made, unlike such venerated male directors such as Todd Haynes (the executive producer of Certain Women, incidentally) or Richard Linklater, whose work similarly elevates the everyday. But Reichardt has persevered with an uncompromising integrity, marching to the beat of her own drum and succeeding in carving out a meditative and elegiac niche in a fast-paced industry that prizes entertainment over observation. And thank goodness she has, Certain Women, with its quiet yet deeply stirring Romantic integrity, proving her finest work yet.

Certain Women is in cinemas nationwide from today.