Osman Ahmed explores the prodigious fashion photographer's penchant for rule-breaking interior design

There are benefits to being a snob: mainly that one’s surroundings are often much more considered than less fussy specimens. Beautiful objects and the finer things in life – which doesn’t necessarily mean the most expensive – are celebrated, curated and appreciated. Anything less than exquisite won’t quite make the mark for the true snob. Snobbish types are inherently creative collectors, if only of out of a desire to differ from the rest. Cecil Beaton was the snob’s snob. Although he came from fairly ordinary beginnings, he catapulted himself into the glamorous world of high society as the photographer-writer-diarist-and-all-round-creative in the interwar years, taking to New York and eventually returning to Britain with a scandal or two in his pockets. Last year, a lusciously heavyweight tome from Rizzoli, Cecil Beaton at Home: An Interior Life, was published, dedicated to Beaton at home, framing his biography through the grand and lesser-so houses he inhabited throughout his life.

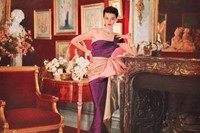

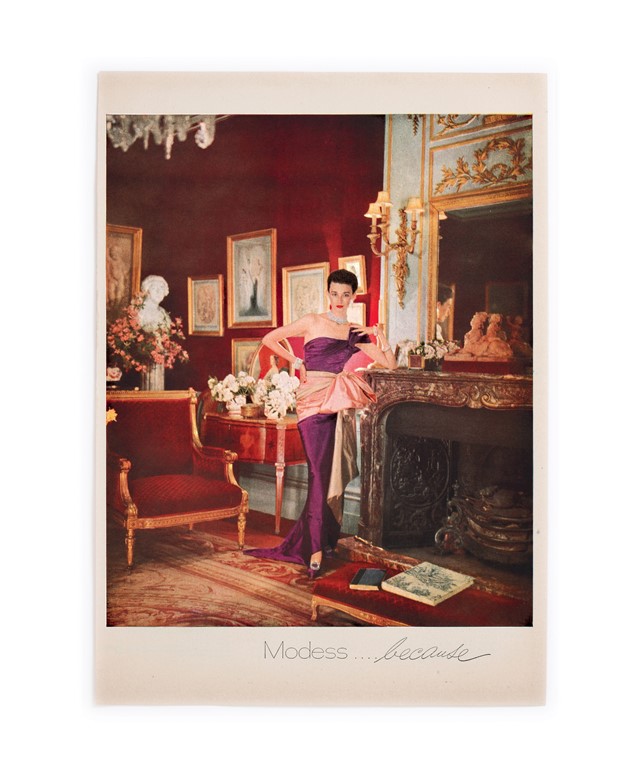

Beaton grew up during an era of Edwardian opulence, and was one of the original Bright Young Things who took to a cocktail of surrealism and hedonism in the aftermath of the Great War. Of his many houses, Ashcombe House, a remnant of a sprawling estate in the chalky Wiltshire Downs, was his most cherished. This was where he built a gilded Rococo circus-themed bedroom, complete with a Botticelli-esque shell-laden bed frame draped with red and gold silk. By his bed was a framed rose given to him in 1932 by Greta Garbo, the silver screen icon who would later become his lover.

Downstairs, the white bathroom featured outlines of the hands of guests with their names signed inside. In an earlier London property, 12 Rutland Court, Beaton’s bedroom was papered in floral damask pattern onto which small cut-outs of photographic portraits and sequins were applied, with a sequin-trimmed mirror reflecting a half-tester bed with a bedspread of multi-coloured pom-poms. His friend, interior decorator Syrie Maugham, was an enduring influence, and what may sound bizarre to today’s sensibility was a powerful antidote to homogeneity at the time (the scent of which still lingers as a counter to today’s pervasive white-walls-and-fougère interiors).

“Taste breaks out all of the rules; as soon as it is pigeon-holed it is dead,” wrote Beaton in 1972. “It must always renew itself, and be seen in new perspectives. Sometimes it can’t be recognised – but there is a hidden logic about it. The obvious becomes vulgar – and so taste has to invent something strange about it. What is good taste at one time is bad taste at another. Some are born without it, but it cannot be applied from outside (having a decorator in doesn’t fit the bill). John Betjeman is right when he talks about ghastly good taste – meaning the obviously tasteful. People should try to invent for themselves – only can something ‘alive’ can be truly tasteful.”

Cecil Beaton at Home: An Interior Life is out now, published by Rizzoli.