Douglas Greenwood unpicks the Austrian arthouse auteur’s latest masterpiece, which premiered at the 70th Cannes Film Festival this week

Only a handful of directors can call themselves a winner of the Cannes Film Festival’s coveted Palme d’Or. Francis Ford Coppola took one home in 1979 for Apocalypse Now, while Martin Scorsese grabbed one for Taxi Driver in 1976. The Austrian arthouse auteur Michael Haneke is also included in the illustrious list of recipients, winning the award for the cold, complex pre-war drama The White Ribbon in 2009, and then again for his story about the duty of lovers and reliance, Amour. Rumour has it that his latest film, Happy End, could turn his Cannes streak into a hat trick.

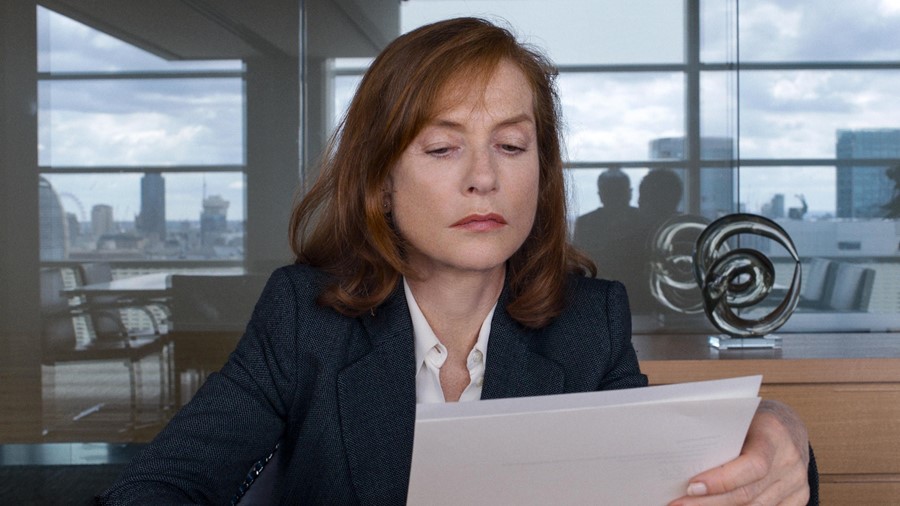

No film playing at this year’s festival has been shrouded in as much secrecy as Happy End (2017) has. Haneke likes to keep his cards close to his chest, and so the information his admirers were provided with was scarce: a short, nondescript log line (“A snapshot from the life of a bourgeois European family”) and the promised return of French cinema royalty Isabelle Huppert. To find out more about Haneke’s most guarded film yet, AnOther caught the film at its Cannes premiere, breaking down what you need to know about its twisted plot, spectacular cast, and the director’s new-found love for vacuous pop culture.

Ignore the positive title: this is peak-bleak Haneke

From the first rumours that were swirling around inner arthouse circles, we were led to believe that Happy End would be about a wealthy, Calais-based family caught up in the European refugee crisis. Although that’s one of many plot lines here, it never takes precedence over a story about a family that seem to be woefully unsatisfied with their luxurious existence.

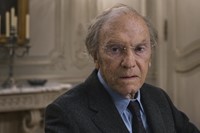

Set in a grand manor in Northern France, the film follows the Laurent family: a Calais-based clan that have earned their wealth from a lucrative, but failing, construction business. The entire family live under one roof: the ageing patriarch Georges who founded the company, his two children Thomas and Anne, Anne’s alcoholic son, and Thomas’ wife and young children. It’s a hotbed of insular, broken characters, all trying to make sense of each other’s issues while remaining blissfully ignorant to the harrowing events happening on their doorstep. A typically existential film for Haneke, it unfurls so meticulously that there’s little sign of that eponymous ‘Happy End’ ever arriving. But that doesn’t mean the film is boring. Instead, it taps into our strange fascination with observing people on the verge of intimate disaster, asking us who we should be siding with when times get tough.

Isabelle Huppert and her co-stars are on top form

Although famed for his ability to work in a breadth of languages, often using French, English and German-speaking actors, Haneke has a keen eye for Francophone talent. Happy End is no exception to that rule, as Isabelle Huppert returns to work with her long-term collaborator for the fourth time. In her role as Anne Laurent, the appointed director of the family’s construction business, Huppert delivers a restrained and typically great performance. But the film’s real scene stealer is a young Belgian actress with a much smaller repertoire under her belt: Fantine Harduin. In the film she plays Eve, the 12-year-old child of Anne’s brother who arrives in Calais following her mother’s unfortunate attempted suicide. She’s morose, emotionally fractured and intimidating, managing to outshine her older co-stars and spellbind her audience with her poise.

It has a killer karaoke scene

Those familiar with Haneke’s work will know that he’s able to shift seamlessly from somber scenes into moments of belly-aching black comedy. Although the laughs are notably restrained in Happy End, there are a couple of moments that allow his sense of humour to shine through. Take, for example, a scene midway through the film in which we watch Pierre, the son of Huppert’s character and eventual heir to the family’s dwindling fortune, drunkenly warble and breakdance his way through a rendition of Sia’s Chandelier. For a 75-year-old man with a penchant for timeless themes in his films, this off-kilter moment of popular culture hits you like a heavy, Haneke-esque ton of bricks.

Strangely, Haneke scolds the way we use social media

The film starts with a strange segment of camera phone-filmed vignettes. In one, Eve eerily dictates her mother’s actions as she gets ready for bed, watching from the shadows through what looks like a Facebook Live stream. She types words: ‘gargle’, ‘smear cream’ and ‘flush the toilet’ in sync with her mother’s mundane tasks. It’s simple, but unsettling and voyeuristic. Later, she turns the camera towards her pet hamster, admitting to lacing its food with her mother’s depression medication. Haneke, ever the sadist, makes us watch as the rodent’s body goes stiff.

Throughout the film, methods of communication in a digital age are put on pedestals and criticised for all of their dangerous abilities: providing a platform for sordid love affairs, making us numb to mindless violence. A hell of a lot of filmmakers try to do what Haneke does and fail, appearing totally out of touch. Instead, in Happy End, the famed Austrian auteur sticks to the themes that he executes so well: dwelling on what makes his audience uncomfortable, and forcing them to confront them through his terrifyingly taut camera lens.

Happy End premiered In Competition at the 70th Cannes Film Festival. It will be released in the UK later in 2017.