The Yves Saint Laurent Haute Couture archive is the stuff of fashion fairytales. Behind the doors of 5 avenue Marceau, across the same threshold that each of Saint Laurent’s private clients once passed, is the perfectly preserved world of the master of couture. It contains looks, accessories, sketches, toiles and specification sheets from every collection. The shoes, the dresses, the earrings, have only ever been worn once, for the show in which they were first presented. The delicately curled feathers affixed to garments hold the same form as they did decades ago; each and every sequin is in its original place. “I have everything, of course,” says Pierre Bergé, Saint Laurent’s partner in life and business. “I kept everything, from the very beginning.”

Today, we are sitting in Bergé’s office at the Fondation Pierre Bergé-Yves Saint Laurent in Paris, a space he has occupied since the 1970s, and the walls are lined with images of Saint Laurent, from Warhol paintings of the designer to framed photographs of the couple throughout their life together. This foundation is the material realisation of Bergé’s life’s work, a life that he devoted to making Saint Laurent’s possible. He is the man who built the business that gave Saint Laurent his creative freedom and the man who, 50 years later, closed the designer’s eyes when he died. If the clothes, and the archives that catalogue them, are legendary, then the relationship between Saint Laurent and Bergé is, too. Admittedly, their relationship was fraught with Saint Laurent’s personal struggles – the addiction and depression that both he and Bergé were remarkably open about throughout his life – but, “It was never difficult,” Bergé says now. “I just loved him. He just loved me. It was very easy.”

“I just loved him. He just loved me. It was very easy” – Pierre Bergé

The two men met for the first time in 1958, following Saint Laurent’s first show for Christian Dior, where he had been appointed the couturier’s successor at the tender age of 21. Bergé had never before attended a fashion show – after all, he was a bohemian book dealer at the time, and “had a little scorn for fashion”. But he was a close friend of Dior himself and so, out of respect, he went backstage. A few days later, the Paris editor of Harper’s Bazaar, Marie-Louise Bousquet, invited Bergé to La Cloche d’Or for a dinner she was holding in Saint Laurent’s honour, and they fell in love.

Four years later Bergé was at Saint Laurent’s hospital bed (he had suffered a nervous breakdown two weeks after reporting for duty for the Algerian war), telling the young designer that, after a period at the house that had seen him dubbed a ‘boy wonder’ by the fashion press, he had been quietly replaced at Dior by another designer, Marc Bohan. The two immediately decided to set up shop. “I was young and probably stupid,” Bergé remembers. “When he said we have to open a couture house together, I said yes. Ten minutes later, when I was alone in the courtyard of the hospital, I said, ‘My God, what can I do?’ But I did it.” And so he went about suing the house of Christian Dior for breach of contract, and with that settlement (alongside funds from an American investor), founded the company. It was an about-turn: “I didn’t want to be a businessman,” he says. “I refused to be a businessman – but I became a businessman for Yves. To help him. To save him. To give him back his place.”

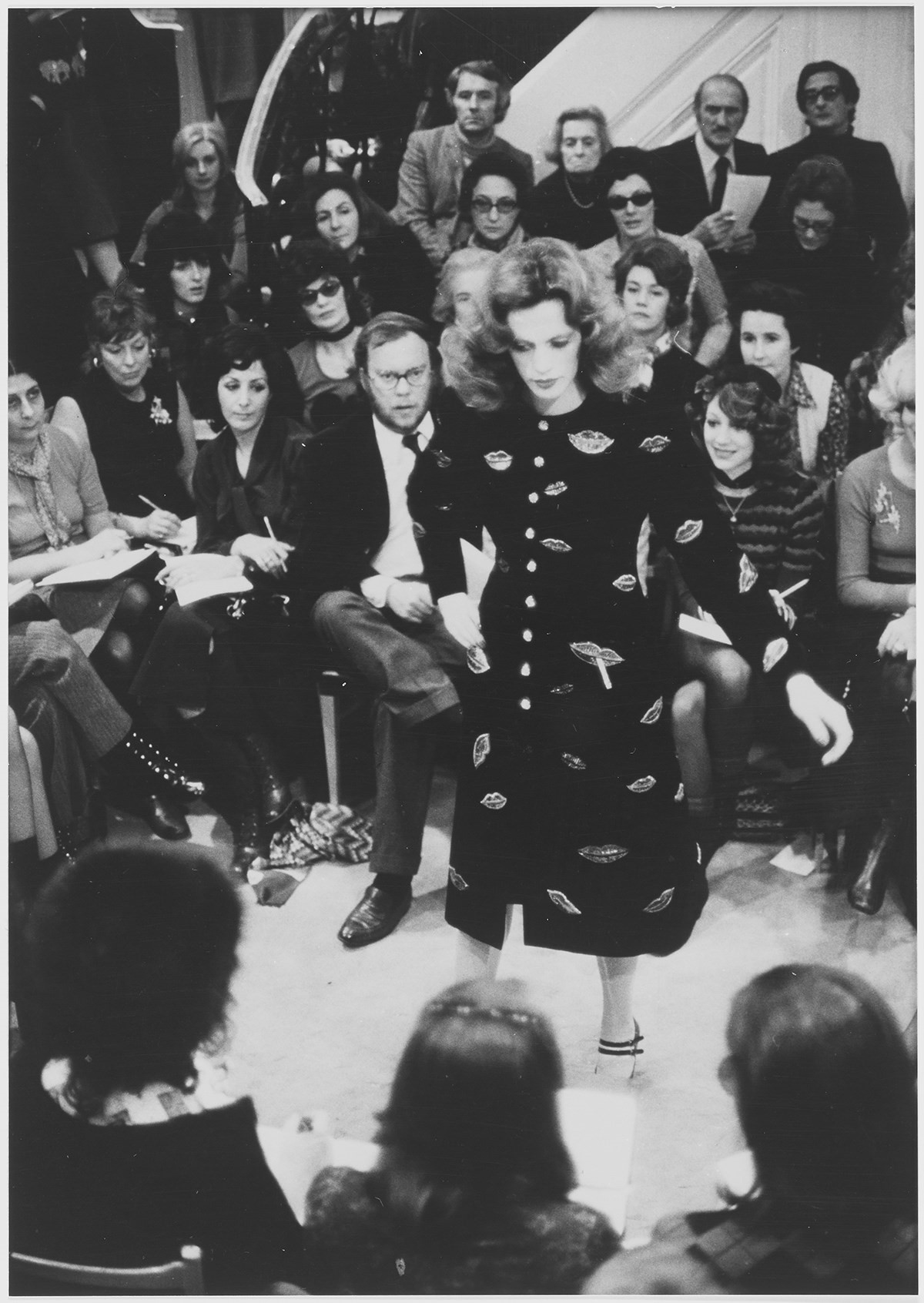

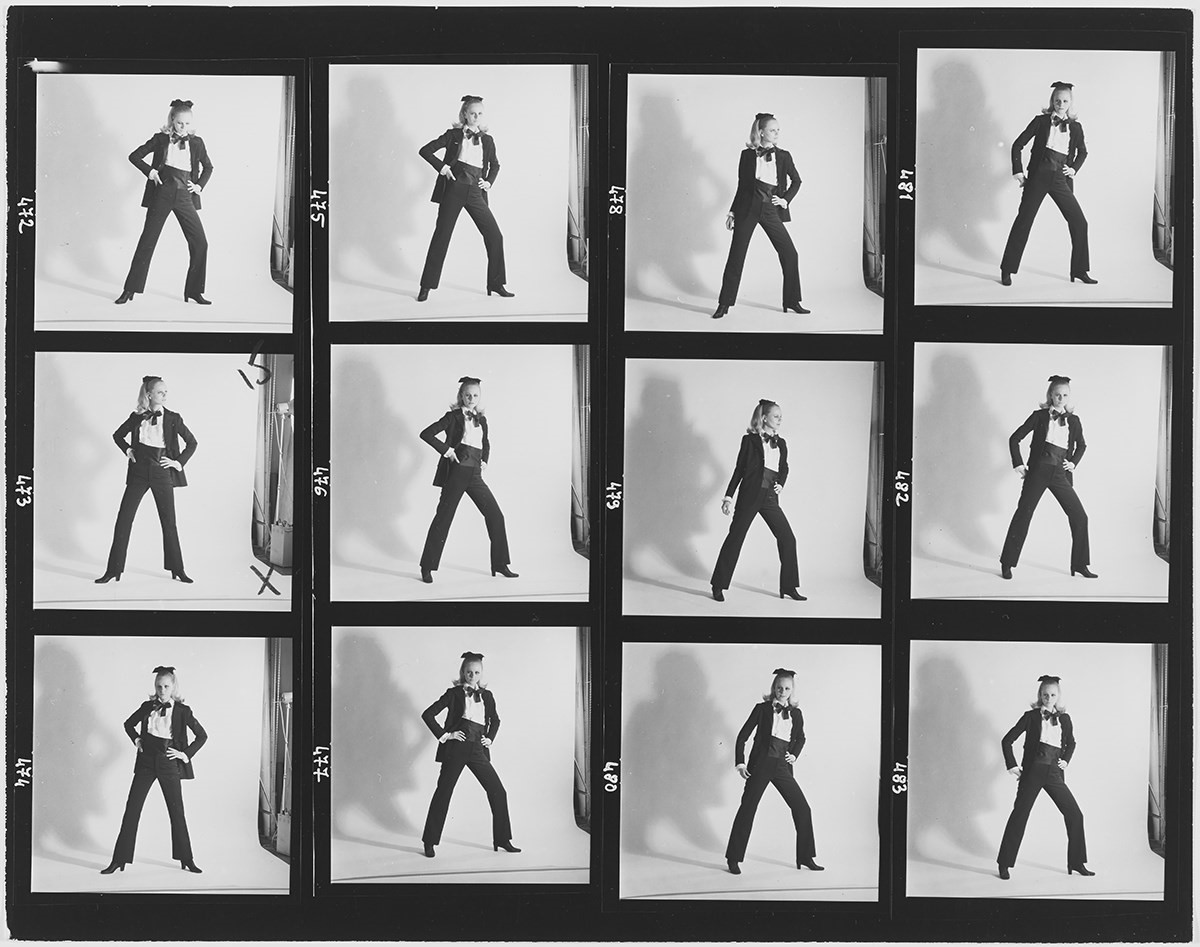

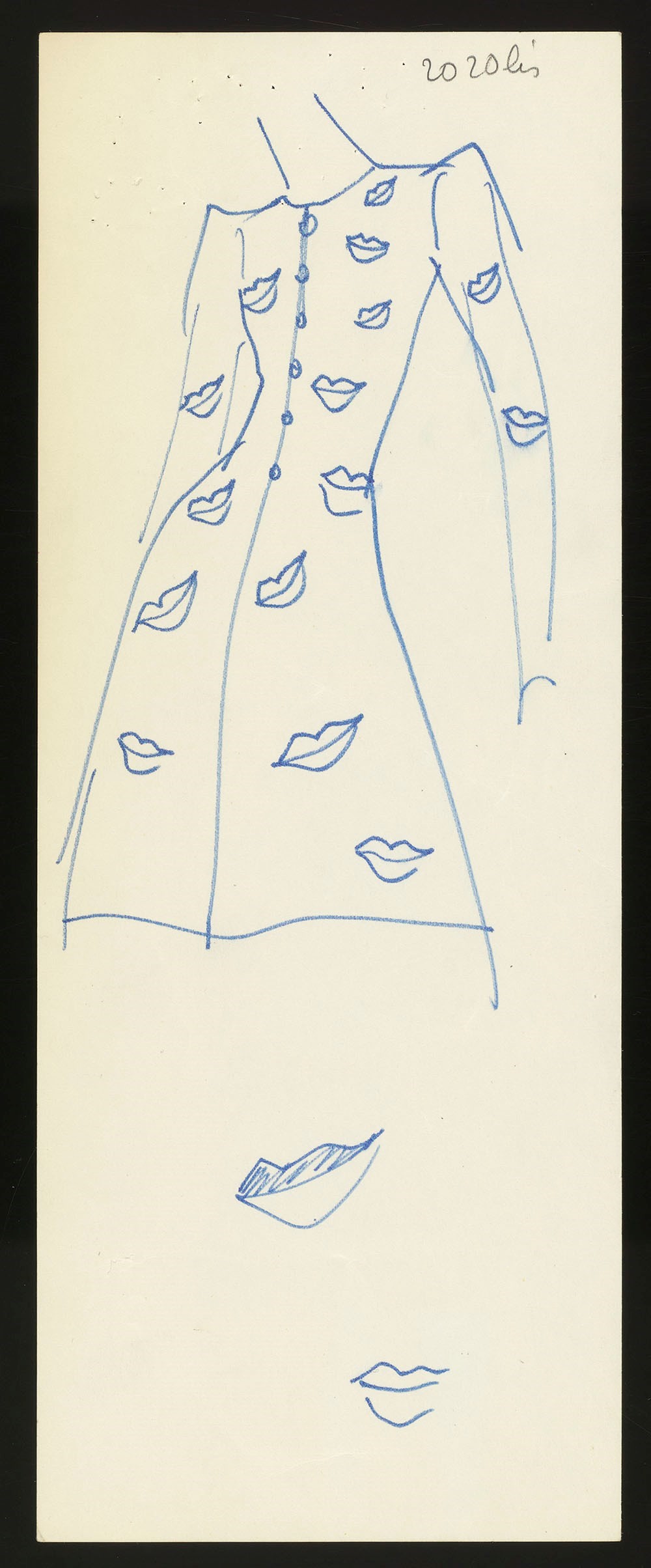

Decades on, and Saint Laurent’s legacy is one that can scarcely be précised. A tour through the archives spans not only decades of fashion history, but equally traces the 20th-century emancipation of women and their wardrobes. Famously, and much to the derision of his contemporaries, it was Yves Saint Laurent who popularised the trouser suit for women. And it was Yves Saint Laurent who first advocated for diversity on the runways, casting models from Rebecca Ayoko and Katoucha Niane to Iman and Naomi Campbell. It was Saint Laurent who shattered taboos and bared the models’ breasts on the runway in a statement of feminine strength; Saint Laurent who revived the 40s wartime silhouettes; Saint Laurent who invented the concept of ready-to-wear as we know it today, making his rarefied world accessible to ordinary women.

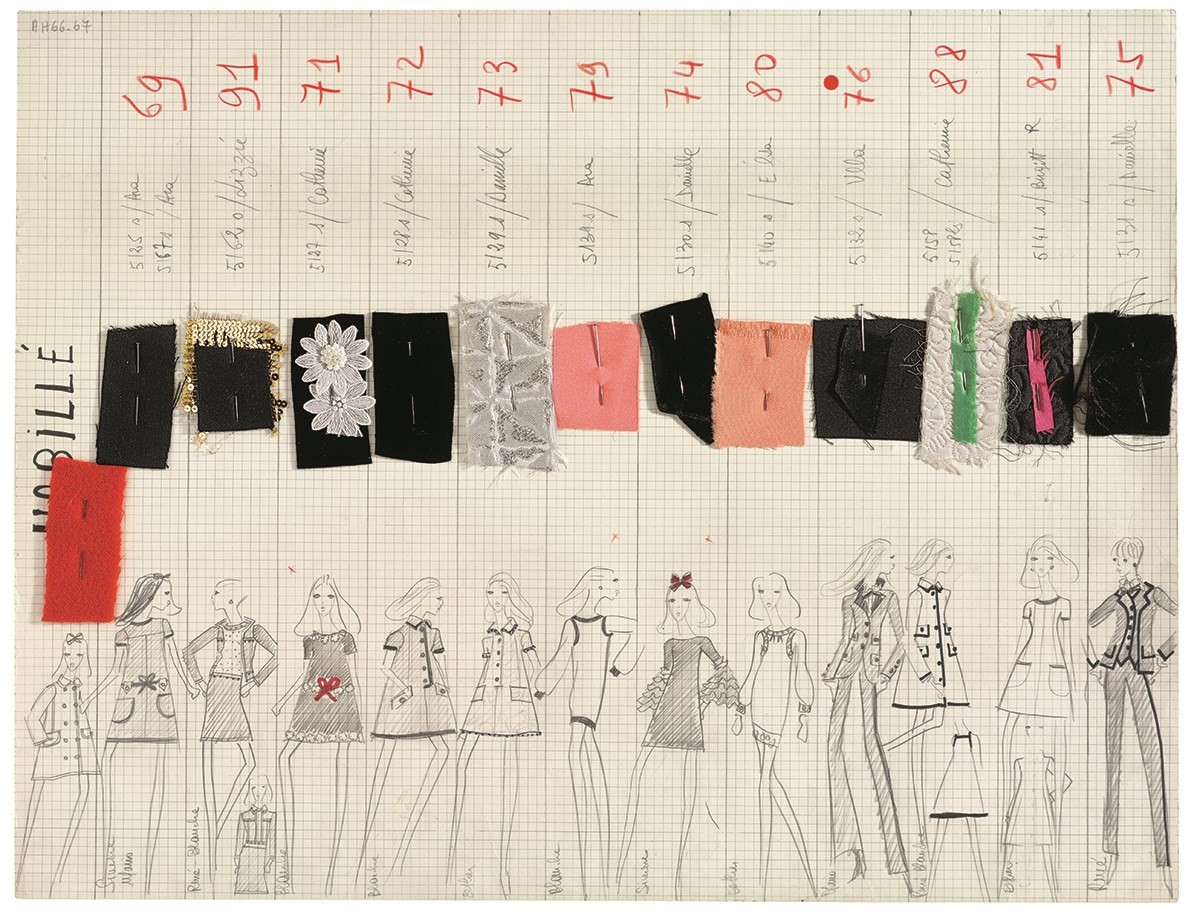

“Saint Laurent gave power to women,” Bergé says. “When a woman was insecure, Saint Laurent garments gave them security. It’s true.” Now, conserved at a particular temperature, particular humidity level, suspended within mousseline shrouds and archived within metal libraries, are those same pieces, the backstage Polaroids of the models wearing them, and the sales ledgers documenting each and every customer’s investment. Currently, in order to explore this archive, which is preserved by seven full-time conservators, you must wear a lab coat and be guided by an archivist. But, with the opening of the Musée Yves Saint Laurent this October, it will be given new life.

The museum will exist in two parts: the first, situated in the same building where Saint Laurent once worked and Bergé now sits, will be dedicated to the designer’s legacy and, for eight months of the year, will show an ever-evolving retrospective of his oeuvre. This evolution is in part due to the vast amount of clothing on offer, and to the fact that, for preservation’s sake, these garments are only allowed to exist outside their protective bubble for specified periods of time – in fact, they must be given days to acclimatise to new air upon leaving the archive at all, much like a naval officer entering the decompression chamber of a submarine. The remaining four months will be dedicated to specific facets of his work – a particular collection, for example, a type of garment, or an enduring theme. The second museum, in Marrakesh, will have its own retrospective alongside an auditorium for performances and exhibition space for artists, or cultures, that influenced or inspired his work – an immersion into the aesthetic universe that he inhabited.

“Saint Laurent gave power to women. When a woman was insecure, Saint Laurent garments gave them security. It’s true” – Pierre Bergé

These parallel museums make perfect sense – after all, Marrakesh was so particularly beloved by both Saint Laurent and Bergé that, in 1966, when they boarded the Paris-bound aeroplane after their first holiday there, they already held in their hands the deeds to a home in the city. They went on to oscillate between Marrakesh and Paris. Saint Laurent would conceive his collections in the former, secluded from the media spotlight that was both a blessing and a curse throughout his career. Then, “Since 1966, we bought two more houses, and a public garden,” Bergé says, referring to the renowned Jardin Majorelle, where his partner’s ashes are now scattered. “It is thanks to that garden that I decided to create a Saint Laurent Museum. I have learned that it is possible to receive 800,000 people a year there. I have learned it is ‘touristique’. I had the chance to buy an empty place next to the Jardin Majorelle, on rue Yves Saint Laurent. It makes sense.”

To fund an endeavour such as this is no small undertaking: the investment required to build these sorts of spaces would be prohibitive to almost any other man. But this is a love story of epic proportions and, as such, in order to fund it Bergé has spent the past decade selling off the collection of art, antique books and wine that the duo amassed during their life together. To frame this in comparative terms, when Yves Saint Laurent’s ready-to-wear and cosmetics business was sold to the Gucci Group in 1999, Saint Laurent and Bergé received $70 million of the $1 billion deal to give up rights to the YSL brand. But the Matisses and Picassos, the volumes of Louise Labé and the notes of Marquis de Sade that once comprised Saint Laurent and Bergé’s belongings? They sold for more than €400 million in what has been called “the sale of the century”.

When I ask Bergé whether there is anything that he longs for or misses, he responds abruptly, “Non”. But then, when I ask if funding the museums was the only reason he decided to sell, he softens, in the manner he seems only to assume when speaking about Saint Laurent. “It is not the only reason,” he says, quietly. “It is also because I don’t want to continue to possess that collection alone, without Yves. I don’t want to do that.”

That’s what is remarkable about Pierre Bergé: that he is not nostalgic, has no interest in enshrouding himself within the world’s most coveted masterpieces, but is simply determined to propel Saint Laurent’s legacy into the future. “I hate the past,” he says resolutely. “I love the future. I love today and I love tomorrow. Probably even better than today.” While the Musée Yves Saint Laurent is founded upon a historic archive of insurmountable detail, and Saint Laurent himself was so besotted with Proustian nostalgia that he would often go by the pseudonym Monsieur Swann, now Bergé’s aim is simply to preserve this world for future generations. “This is not nostalgia,” he says. “I hope that the museum will show how Saint Laurent was a visionary... will show his style, and what style is. Why style is the only important thing.”

When these words are spoken with such abject resolve, they seem destined to come true.

This interview originally featured in the Autumn/Winter 2017 issue of AnOther Magazine which will be on sale internationally from 14 September, 2017.